Bouquet Of Barbed Wire

In Rabbit-Proof Fence the Stolen Generations of indigenous Australian children make an apt subject for a popular political tear-jerker. By Adrian Martin

Many manuals for scriptwriters today preach a storytelling wisdom that has more to do with the shallow entertainment formulas of Steven Spielberg and George Lucas than with the depth and breadth of narrative technique down the ages. The hero, the journey, the homecoming... in the 21st century such clichés provide not only chapter headings in teach-yourself books but handy slogans for promotional campaigns. "1500 miles is a long way home," proclaims the tagline for Phillip Noyce's Rabbit-Proof Fence, above a sepia-tinted shot of one little girl holding another in her arms as she determinedly makes her way alongside a barbed-wire fence. This publicity does not lie: it would be hard to find a purer example of a story about a heroic journey home, a story of (as Noyce boasts) the "courage and determination" that finally mend a broken family.

The girl at the centre of Rabbit-Proof Fence's publicity image is Molly Craig (Everlyn Sampi), and the time is the early 1930s in Jigalong, Western Australia. Her true story has been recorded by her daughter Doris Pilkington Garimara. Molly and her younger sister Daisy (Tianna Sansbury) and cousin Gracie (Laura Monaghan) were wrenched away by police from their mothers and grandmother and relocated in a children's centre 1,200 miles away at Moore River. Molly knows that by following a fence that bisects Australia from north to south she can find her way home. So the three girls embark on this dangerous journey by foot, without provisions and with the authorities close behind.

This story may seem exceptional but is in fact typical. It has a historical context which has been the stuff of daily news reports and unquenchable public debate in Australia over the past five years. This history now routinely comes to us in language and imagery that conjure passion and outrage, even a sense of melodrama - emotions that are necessary to convey the enormity of the pain involved and the issues at stake. The Stolen Generations are indigenous Aboriginal children who between 1910 and 1970 were taken from their families and relocated by government decree. This long-buried and deeply shameful episode in Australian history was finally presented to the public in 1997 in an official report titled Bringing Them Home. As political commentator Robert Manne has described it: "Story after story spoke of psychic and cultural dislocation; terrifying loneliness; physical, sexual and moral abuse; and of continuing pain, numbness and trauma experienced after an often bewildering and inexplicable removal from mother, family, community, world."

In the wake of the intense public reaction to this report Australian prime minister John Howard caused enormous unrest by refusing - as he still refuses - to offer an official apology to the Aboriginal people for the institutionalised injustices inflicted on them. Sorry seems to be the hardest word for Howard and his supporters. Their line is that any shame or guilt is in the past, a matter of ancient history. Meanwhile, a small army of conservative political theorists has drawn the media spotlight to claim that the story of the Stolen Generations is an ideological myth, a fabrication, at the very least a gross exaggeration. Like the Holocaust deniers, these radical conservatives examine and quibble over numbers: was it really one in three Aboriginal children affected or was it closer to one in ten? And if no one can truly say, should we accept that anything horrible happened at all? It is in opposition to such brutally literal reasoning that the overflowing emotion of Rabbit-Proof Fence acquires its true political force.

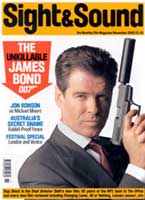

Within a national cinema that too rarely takes on topical issues with any sense of urgency or commitment, Rabbit-Proof Fence has become an emblem of Australia's burgeoning 'reconciliation' movement, which is committed to healing the wounds inflicted by white settlers on the country's original inhabitants. There is, of course, more to this sorry history than the Stolen Generations, but it's the traumatic plight of the abducted children rather than debates about ownership of land or exploitation of artistic traditions that has come to symbolise the collective wound which demands healing.

But while Rabbit-Proof Fence has become a kind of flagship, it in no way resembles the dour, modestly scaled, politically correct art that so often emerges from Australia's battling independent film-makers. Rabbit-Proof Fence comes on like a Hollywood film - a tear-jerker, a spectacle, complete with a rousing score by Peter Gabriel and boldly stylised cinematography by Australian expatriate Christopher Doyle, as well as an ingenious pre-publicity campaign about the search for 'child stars' in Aboriginal communities that made every populist tabloid and supermarket-checkout magazine in the country. What's more, it is (as Aborigines say) a 'whitefella' film about blacks, and thus is a priori classed in the company of such politically dubious predecessors as Bruce Beresford's The Fringe Dwellers (1986) rather than such authentic indigenous cultural artefacts as Ivan Sen's Berlinale winner Beneath Clouds (2002). Rabbit-Proof Fence has thus to negotiate several danger zones before it can win over the hearts and minds of the diverse audiences who have an investment in the Stolen Generations issue.

Any politically contentious real-life incident that's dismissed by some as fantastic is bound to have an intriguing rendezvous with cinema. Should such a movie try to convince unbelievers that what to them is implausible is in fact believable, via the medium's powerful reality effect? Or should it seize the fantastic, wish-fulfilment potential of its subject matter, via cinema's no less powerful tie to the realm of dreams and desire? This is the difference between, say, Spielberg's largely naturalistic, meticulously reconstructed Schindler's List (1993) and Emir Kusturica's wildly allegorical and fanciful Underground (1995).

The aesthetic decision Noyce took was inflected by his wish to make a film that could function not as a small arthouse success but as blockbuster entertainment, as "a universal story that goes beyond its time and its setting." And with that comes the determination to make a film that does not simply preach to the converted but grabs and moves a mass audience. Noyce is well placed to contemplate the difficulty of bringing all these goals together, given the stark distance between the left-wing politics of his early Australian films Backroads (1977), Newsfront (1978) or Heatwave (1981) and the bombastic, every-which-way opportunism of such slick Hollywood assignments as Sliver (1993) and Clear and Present Danger (1994).

Ultimately Noyce tends more to the fantastic than to the realistic. Rabbit-Proof Fence is certainly full of carefully observed detail, and the central trio of non-professional child performers provides an appealing aura of naturalness. But at every moment the film aspires to the level of the mythic, especially once the children begin their trek. Doyle's picturing of the Australian outback is quite unlike anything seen on the screen since Nicolas Roeg's Walkabout (1971), another film about a long and fraught journey home undertaken by displaced children. From the ambiguity of its opening, Antonioni-like shot, where one can't make out the scale of what one's seeing, to its eerie vistas of ground and sky saturated by light or dominated by the primal elements of sun or rain, Rabbit-Proof Fence presents itself as an expressionistic portrait, more fixed on conveying a kaleidoscopic succession of emotional sensations than merely documenting the stages of a journey.

In Australia's current political climate, this fantastic- mythic approach was a risk, though presumably a calculated one. The response of the Australian's film reviewer Evan Williams shows a conservative mindset grappling, a little uneasily, with the film's undeniable emotional impact: "Rabbit-Proof Fence has been made with such transparent humanity and idealism it scarcely seems to matter whether the story is true or not." This comment at once implies, rather scurrilously, that the story is not true, while also conceding that it may not have to be true, that its galvanising, utopian effect on a public of ordinary spectators is potentially more significant than mere verisimilitude. In Australia at least Noyce's gamble has paid off: Rabbit-Proof Fence is among the most successful and longest-running local films of 2002, with a third of its takings coming from regional areas.

The film does have its dramatic problems. What demonstrates Noyce's Hollywood-nurtured art and craft - the many scenes built on tense moments of waiting and the piercing or searching gazes of characters - also serves to mask an absence of narrative intrigue inherent in the real-life material. Not only is such a long journey by foot difficult to render within a condensed, narrative form - Theo Angelopoulos or Béla Tarr, cinematic poets of the dogged stroll, might have fared better with this premise - but the difficulty is exacerbated by the fact that Molly's story has very little incident and few turning points. Beyond the devastating moment when Gracie, who has decided to separate from her cousins, is nabbed again by swooping policemen, not much happens: kindly strangers are met along the path or at isolated homesteads (such as Mavis, played by popular Australian actor Deborah Mailman) and a tracker in the service of the police named Moodoo (played by David Gulpilil, the children's guide in Walkabout and the star of Rolf de Heer's extraordinary 2002 film The Tracker) silently locates the traces left by the children while interacting tersely with his white superiors.

What replaces conventional intrigue is a magical element, reminding us of the book's full title Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence, with its Wizard of Oz association. As in Peter Weir's The Last Wave (1977), which also featured Gulpilil, mystical and supernatural elements of Aboriginal spirituality are roped into the plot. These moments border on romanticised, 'whitefella' cliché, but are undoubtedly among the movie's most effective: the passage in which the children seem to communicate mentally with their mother and grandmother over a vast distance by holding on to the fence and swaying it; or the deliberately spooky twilight scene in which Constable Riggs (Jason Clarke) encounters the suddenly menacing apparition of the same mother and grandmother among a tangle of trees.

Where the mistakenly assumed realism of Rabbit-Proof Fence has stirred the most heated debate is in its depiction of a crucial real-life figure, A.O. Neville (Kenneth Branagh), chief protector of Aborigines of the period and one of the architects of the policy that created the Stolen Generations. In a book published in 1948, Australia's Coloured Minority: Their Place in Our Community, Neville wrote: "The scientist, with his trained mind and keen desire to exert his efforts in the field investigating native culture and in studying the life history of the species, supplies an aid to administration." As indigenous commentator Kim Scott has pointed out, Neville's science was derived essentially from eugenics. Noyce and screenwriter- producer Christine Olsen faithfully condense the essence of Neville's racial theory in a slide lecture presented to a group of society ladies: he believed it would be possible to "breed out the colour" from so-called half-castes by management of their marital unions.

What are we to make of Neville today? His apologists paint him as someone unfairly put upon, someone who simply tried to improve the lot of the Aborigines as he saw it. In a familiar turn of conservative rhetoric, we are asked to understand Neville within the framework of his own time, not of ours. (Another ambivalently 'benevolent' figure of the period, writer Daisy Bates, has recently been the subject of an Australian essay-film called Kabbarli.) Furthermore, it is insisted that the taking of children from their parents was not a racial policy but a welfare-driven one, applied equally to children of white families in disadvantaged circumstances. But as Liberal ex-prime minister Malcom Fraser (a strong pro-reconciliation voice) has made clear, two distinct policies in the official ordinance governed the treatment of incompetent parenting and the treatment of mixed-blood Aborigines and their families. According to Fraser, Neville paid "a great deal of attention to mixed bloods because their genes had been strengthened by white blood... If they grow up understanding Aboriginal history, language, culture, those things will live on. That was something that Mr Neville didn't want to happen."

Representing Neville on screen is a difficult business in this context. Noyce and Olsen want both to make a strong political critique of the values he embodied and implemented and to respect the individual humanity of the person. According to Noyce, everyone involved "agreed that A.O. Neville was misguided, but he felt that he was saving the Aboriginal race from a fate worse than the one that had been decreed for them." The words Branagh offered to Noyce on set are eloquent: "Look, I can't judge this man, I'm not here to do that by my performance. I'm only here to reveal him." But how can such a 'revealing' ever be politically neutral?

For some viewers at both ends of the ideological spectrum Rabbit-Proof Fence indeed tends to satirical caricature in its portrait of Neville. Ceaselessly pinned in the centre of uglifying, ultra-low or high wide-angle compositions, Branagh plays Neville as a stiff, unfeeling creature. But his performance does intersect with the mitigating conception of the film-makers: Neville less as a rounded, freely determining individual - and thus entirely to blame for his actions - than as the social product of a bureaucratic machine. Neville here is less a person in touch with his feelings than a dutiful functionary, a number cruncher whose scientific philosophy and hyper-rationalist method anticipate the barbaric logic of today's deniers of historical traumas. By always filming Neville on the job, and mainly in his dank office, the movie finds a way to create a shade of pathos for the character while damning everything he did and said in his official role.

Stressing the system over the individual also creates the possibility for a delicious irony: if it's bureaucracy which makes this man, it's also what finally undoes him once matters pass outside his jurisdiction or different ordinances clash. The human reality of the girls, and the traditional culture which strengthens them, proves too rich, too elusive for the system to contain. And so the values underlined by Robert Manne of "mother, family, community, world" can indeed, despite everything, survive. This is the optimistic message Rabbit-Proof Fence offers contemporary Australia.