The Egos Have Landed

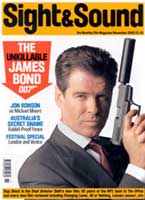

Michael Moore's Bowling for Columbine is worth more than a raised eyebrow, says Jon Ronson

I was worried, in advance, about Bowling for Columbine's hug quotient. Michael Moore's 1989 debut Roger & Me was, to my recollection, hug-free. But his next major film, 1998's The Big One, was packed to the gills with embraces. The Big One chronicled Moore's publicity tour across America, plugging his book Downsize This!. From book signing to book signing, in state after state, he would hug and be hugged by grateful members of the public who just wanted to thank him for being him. Then - like the Spiderman of liberalism, except Spiderman was incognito - he'd shoot off into the night and courageously right a corporate wrong.

What happened? What turned Michael Moore from the savage and hilarious polemicist of Roger & Me - in which he stalked Roger Smith, the CEO of General Motors, in an attempt to get him to visit Flint, Michigan, so he could see the economic carnage he inflicted when he moved his plants to Mexico and Indonesia - into an inveterate on-screen hugger? Rumours abounded, my favourite being that Moore would allegedly insist, when visiting London, that the BBC or Channel 4 fly him Concorde and put him up at the Ritz, but also book him a cheap hotel down the road so when he met journalists they'd believe he was staying in humble circumstances. It seemed the success of Roger & Me - the biggest-earning documentary thus far - had turned him a little crazy.

The documentary movement to which Michael Moore in the US and Nick Broomfield, Louis Theroux and myself in the UK belong - let's call it Les Nouvelles Égotistes - has been through a fallow period of late. The faux-naïf thing (our trademark) has begun to annoy even me. Faux naïfery is a delicate craft which, when mishandled, can be very irritating. A lot of mishandling has been occurring of late, and so a backlash is brewing. In fact, at a recent event I attended at London's ICA, an audience member blamed the four of us for destroying the careers of the Maysles brothers, those direct-cinema pioneers who in the late 1960s exploited new lightweight cameras and sound equipment to achieve intimate portraits of their subjects. "You're nothing but flavours of the month!" he yelled, clearly upset. Was this true? Had we - as he went on to suggest - cruelly trampled the purveyors of documentary truth, elegance and aesthetic vérité in our stampede to the top?

The movement began in 1985 with Ross McElwee's Sherman's March: A Meditation on the Possibility of Romantic Love in the South during an Era of Nuclear Weapons Proliferation. Here McElwee took the money he was given to produce a historical documentary about General Sherman and used it instead to make a film about why he couldn't hold down a relationship with a woman. Much of the film was comprised of McElwee dissecting how he thought the filming was going as he travelled the route Sherman's army took through the South.

That same year Nick Broomfield was in the midst of making a disastrous fly-on-the-wall documentary about comedian Lily Tomlin when he had an epiphany. He was missing all the best bits - the off-camera backstage fights, and so on - and he realised the missing scenes, cut or not shot because they referred to the film-making process, were the most revealing about his subject. His subsequent films - Driving Me Crazy (1988) and The Leader, His Driver and the Driver's Wife (1991) - were comprised entirely of 'missing scenes' and thus reinvented the form. Then I came along and nicked it from Nick Broomfield (whom I still consider the master of the art) for television series from The Ronson Mission (1993) to The Secret Rulers of the World (2001), and then Louis Theroux came along and nicked it from me for his 1998 programme Louis Theroux's Weird Weekends. Over in the US Michael Moore's rendition of the style just evolved, I think, in the way African and Indian elephants just evolved. I was surprised by the accusation made at the ICA - the implication that what we do is utterly divergent from what the Maysles brothers did. The Maysles brothers also distrusted the fly-on-the-wall convention of pretending real reality was unfolding while a camera and sound team were frantically composing shots in the corner. This is why they would include glimpses of themselves in the mirror, for instance. And surely that's all we do - only on a slightly more epic scale?

Some people consider we four central practitioners of the Nouvelles Égotistes movement to be essentially interchangeable in our presentational styles. I would like to take the opportunity to dissect the differences. Michael Moore is a shouter (at CEOs of global corporations, or, if they won't go on camera, at their PRs; at gun lobbyists and powerful Republicans). Theroux and I never shout. Broomfield has shouted, most notably in Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer (1992) at people who made money from his serial-killing heroine.

Moore is an archer of eyebrows (at neo-Nazis, militiamen and less powerful backbench Republicans). Theroux, Broomfield and I also arch our eyebrows at neo-Nazis and militiamen, but I'm trying to stop doing this. Instead I find myself becoming as paranoid as the people I used to raise my eyebrows at. Broomfield too seems to realise that eyebrow- arching is a passé documentary technique. His most recent film Biggie and Tupac (2001) worked because it was passionate and investigative: he cared about his protagonists and managed to turn over some very slimy stones in his quest to discover the story behind the murders of the two rappers.

And Moore is a hugger (especially of shooting victims, low- paid workers and fans of his work). Theroux and I never hug, though Broomfield recently became a neo-hugger (see the final "you make a lovely stew" scene in Biggie and Tupac).

At his very best, in Roger & Me and now Bowling for Columbine, Moore is quite brilliant at creating - using archive material and savage comedy - a political panorama that startlingly interweaves the macro with the micro. One of the most powerful and convincing moments in Bowling for Columbine is his drawing of a parallel between the US selling weaponry to Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, the teenagers who shot up Columbine High on 20 April 1999, and the US providing training and finance to Osama Bin Laden during Russia's invasion of Afghanistan. He even manages to get a representative of arms manufacturer Lockheed Martin to say, "What happened at Columbine is a microcosm of what happens throughout the world." It's as if this representative sees himself as a bystander to these matters as opposed to being at their very heart.

Moore is a superb polemicist, Chomsky with gags, a brilliant collagist of both kitsch archive and liberal polemics. After an opening montage that documents America's obsession with guns throughout its cultural and political history, he is seen walking into a Midwestern bank. "I want the account where I can get the free gun," he says. The bank manager unblinkingly agrees. The only prerequisite to this offer is, apparently, that the account holder isn't "criminally defective". "So it's OK if I'm normally mentally defective but not criminally?" asks Moore. "Yes," says the bank manager. "Don't you think it's a little dangerous handing out guns in a bank?" asks Moore.

After this things dip slightly, with Moore going for a soft target, the Michigan Militia. At one of their meetings, a shooter - a real-estate negotiator when not in fatigues - asks Moore, "Who's going to defend your kids? The cops? The Federal Government?" Moore raises his eyebrows and plays to the gallery with a lame joke. "Do you take one of those guns with you when you're negotiating real estate?"

It's a rare low point. The Michigan Militia was created in the wake of the Ruby Ridge massacre in Idaho in 1992. At Ruby Ridge a young boy and his mother - who was armed only with an 18-month-old baby - were murdered by Federal snipers in a bungled and wholly inappropriate raid on a peaceful (if slightly paranoid) white separatist family. The exact same snipers committed a similar atrocity a few months later at Waco, Texas.

So the Michigan Militia's concerns about the Federal Government deserve to be treated with something other than arched eyebrows. The Weaver family at Ruby Ridge and David Koresh's parishioners at Waco were victims of liberal America - gunned down because their peaceful, if odd, beliefs didn't fit the prevailing norm. Moore ought to be championing these underdogs in the same way he champions victims of corporate globalisation, but he doesn't. They are, to him, just wackos. Indeed later in the film he includes a clip or two of the protestors who gathered at Ruby Ridge to support the Weaver family. Again he portrays them simply as gun nuts, without contextualising the cause of their anger. As Randy Weaver once said to me, "The second amendment, the right to keep arms, isn't about hunting or target shooting. It's there to protect the people against a government that can become tyrannical against its own people."

But then Moore's film really takes off. Examining the Columbine High shootings, which - he points out - occurred on the same day that "Clinton bombed some country the name of which nobody in the US could pronounce", he asks, what is it about America that produces so much gun violence? Last year 381 Germans were killed by guns. There were 165 gun deaths in Canada, 68 in the UK, 65 in Australia and 39 in Japan. In the US there were 11,127. "Are we homicidal by nature?" asks Moore. He does a vox pop on the streets of New York. "Canadians don't watch violent movies," suggests a passer-by. "There are no guns in Canada," suggests another. It turns out, of course, that Canadians love violent movies and love guns. The viewer is as flummoxed as Moore. A problem with Moore's less successful work is his intellectual omnipotence, his having all the answers. Here he seems honestly confused.

The turning point comes in an interview with pop star Marilyn Manson, who was absurdly scapegoated for inspiring the Columbine shootings because the boys were fans of his music. But the boys went bowling the morning they killed their classmates. Why was nobody blaming bowling? In the aftermath of Columbine children were expelled from schools across the US, one for pointing a chicken drumstick at a teacher. "Yes, our children were indeed something to fear," says Moore.

Ultimately Bowling for Columbine is a film about fear. Americans are fear junkies and the media provides all the fear they want. Fear of Marilyn Manson, fear of out-of-control children, and - post 11 September - fear of everything, which sanctions US foreign-policy outrages. In grappling with this concept, Moore transforms himself from a political commentator into a philosophical one. His suggestion is that the fostering of fear is a capitalist sleight-of-hand designed to deflect Americans' attention from the things they should be angry about - the things that make money for corporations.

"A country that's this out of control with fear shouldn't have all those guns and ammo lying about," Moore concludes, ending the film by going after the National Rifle Association president Charlton Heston. It's a disappointing climax, which attempts to ape his debut Roger & Me. But Roger Smith was a worthy target, and Heston is not. Sure, Heston was a little foolish in holding an NRA meeting down the street from Columbine High a few days after the massacre. But he's a lobbyist who's not responsible for the murders of little girls, and when Moore leaves a framed photograph of a murdered little girl on Heston's doorstep and wanders away with his head bowed, the pathos backfires. In demonising the NRA - he even accuses them of being the Ku Klux Klan by another name - Moore is himself guilty of inappropriate scaremongering. It's an unsatisfactory ending to an otherwise brilliant documentary.