So Many Moustaches!

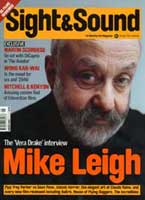

A large find of films that bring the Edwardian world back to life with unusual clarity has been made available by the bfi archive. Nick James introduces the wonders of Mitchell & Kenyon

Much of the time we in multicultural Britain prefer to be confronted with images of ourselves and people like us rather than figures of fiction, fantasy or exoticism. That may be an odd truism of the celebrity age, but it seems irrefutable. We watch reality television and read magazines like Heat knowing that we enjoy the people who feature in them most when they look and behave much like ourselves and our neighbours – sometimes loveable or charming, more often clumsy or wrong-headed, occasionally plain crude or ghastly. This shared but solipsistic curiosity (a sense of community at one remove) is regularly described by cultural analysts as a comfort-seeking reaction to the alienating pace of change set by the revolution in electronic communications media. But could it be rather that the immediate fascination of any new medium is to be found in what it reveals about ourselves?

Go back 100 years to the Edwardian era and you'll find direct equivalents to these current interests. This too was a time of rapid and intense technological change. Rather than the internet and multi-channel television, the punter of the early 1900s had new popular newspapers like

Three Metal Drums

This was a moment when the 'masses' - as the newly visible populace was dubbed by horrified intellectuals – were growing in confidence. Britain was at its peak as an imperial and industrial power, and as a consequence many ordinary working people had some disposable income for the first time, as well as some leisure hours to occupy following the introduction of a half day off work on Saturdays. These are the circumstances that created football as a mass spectator sport, saw a love of parades and fairgrounds blossom and fostered the spectacle of music hall and theatre. But cinemas were not widely built until the 1910s, around the time when classical narrative cinema began to get a dominant hold of the medium of film as the first flush of amazement at the science of projection waned. Our own familiarity with the moving image may have made us indifferent to the ubiquity of the video camera, but the appearance of a film camera in the early 1900s was a remarkable event, greeted with a sense of wonder clearly written on the faces of the Edwardians who proudly posture, wave or cheer for the camera in the 'reality cinema' local film companies would produce to show at fairgrounds.

Indeed, what we know about this Edwardian era through film has hitherto been based on meagre extant collections of such vintage reels, many of which display symptoms of physical deterioration that impede study of their subjects. In 1994, however, three metal drums were found by building contractors in the basement of a former shop in Blackburn, Lancashire, once the premises of Edwardian film company Mitchell & Kenyon. Through good fortune, these made their way into the hands of local enthusiast Peter Worden, who discovered that the drums contained 826 uncored rolls of nitrate film that consisted mostly of Mitchell & Kenyon's 'actuality' films, many of which were in very good condition, though dirty. Worden passed the collection to the British Film Institute in 2000 to be archived, preserved and copied, a painstaking process that has taken four years to complete.

These films, according to the bfi's book of essays published in tandem with a new BBC series of three documentaries entitled The Lost World of Mitchell & Kenyon, "were the product of a highly developed system of commissioning by itinerant regional showmen and were intended to be an evolving contemporaneous source of entertainment and news." They existed in a context where film was part of a culture of public spectacle. Fiction films were often brief one-reel 'actualities' such as James Willamson's rescue stories Attack on a Chinese Mission – Bluejackets to the Rescue (1900), Fire! (1901) and Two Little Waifs (1905) or adaptations like Cecil Hepworth's extraordinary Alice in Wonderland (1903). But more typical was the output of the American entrepreneur Charles Urban, who came to Britain both to distribute and make a variety of films, specialising at first in 'actualities and news' but gravitating towards science and travel. His boast was: "We put the world before you."

If your expectation of viewing such early films is of a dismal experience - the flickering image faded, blotted and scored, the movement of the figures like St Vitus' dance - then prepare to be astonished at the crisp clarity and vivid reality of the reels in much of the Mitchell & Kenyon find. My own sense of wonderment was echoed in the reaction of Mick Judge when confronted in the first of the BBC documentaries by images of his great-grandfather Paddy Judge turning out for the local rugby team in 1901: "To see him running around, a man who was born 90 to 100 years before I was, to actually see him physically doing things is incredible." Watching these films – of people leaving the factory gates at Jute Works in Barrow or Pendlebury Colliery, of public processions and parades, of sporting occasions like Manchester United's first match after the team changed its name from Newton Heath, of street scenes shot from trolleys and trams in Bradford, Halifax, Nottingham, Norwich and Sunderland – makes you acutely aware that these are sentient beings who once existed. Photographs are much less effective at conjuring this magic: their stillness has a distancing effect, an interring of memory into its own ossified archive.

Teeming humanity

The results achieved by the restoration team are so good there's a hyperreal dream-quality to them. When we watch the families dressed up for a walk along Morecambe sea front or lining up for the Hollow Drift Children's Procession – adults in bowler hats and bonnets, children in knickerbockers and lacy frocks – we're seeing the ghosts of a phantasmagorical era made flesh. At first glance these children could be taken for J.M. Barrie's lost boys or Henry James' haunted siblings from The Turn of the Screw. As Dan Cruikshank, the whispery, slightly over-enthusiastic presenter of the trio of BBC programmes, says: "There are so many moustaches!"

The imagery of the Edwardian era – the elaborate clothes and uniforms, the polished paraphernalia of buses and fire trucks, the cluttered formality of the middle-class home – has been recreated for films from The Go-Between (1971) to Finding Neverland (2004). But we are separated from the people of the M&K reels by more than a veneer of Hollywood glamour. Cruikshank remarks of the elderly-looking women at the mill gates that though they appear to us to be in their seventies, they were probably nearer 50, used up by an unimaginably tough life of industrial and domestic drudgery unassuaged by the nutrition and medicines that allow us to grow taller and live longer. We learn that men in Edwardian factories averaged as much as 20 pints of beer a day, adding drunkenness to the hazards of working with unguarded machinery. Pubs were open all hours and even children were allowed to drink. We can marvel even further, then, that large gatherings did not often degenerate into riotous behaviour.

Yet the moving panoramas of northern cities taken from trams and trolley cars do give an overwhelming sense of why the masses struck terror in the hearts of fin-de-siècle intellectuals. Compared to today's indoor urban populations, the denizens of the turn of the 20th century were out on the streets, escaping the crowded, dingy conditions of rooming houses and back-to-backs. Life in Edwardian Britain seems as much a matter of public display as it is today for the peoples of the Mediterranean, and this holds true as much for the middle classes as for factory workers. People really do hook their thumbs into their waistcoats in pride at their public sense of self as they pose for the camera – even the child mill workers.

A claustrophobic sense of teeming humanity is exaggerated by the rhythms of the working day. When mill and factory shifts ended people flowed out of the gates in huge numbers, transforming public spaces into a sea of moving bodies as instantly as football crowds do today. What we can't get from the M&K factory-gate series (a genre established by the Lumière brothers with their 1895 film Sortie des usines Lumière) – as Cruikshank points out – is the cacophony a crowd shod in wooden clogs must have produced when pouring down the cobbled streets. M&K's parade and celebration series depict these men in flat caps and women in shawls transformed on Sundays into genteel-looking folk dressed in their 'best' (which often went back to the pawnbrokers next day to be reclaimed on pay day). Another surprise is seeing from a moving bus how abruptly the city becomes the countryside, without any of today's transitional suburban sprawl.

It would perhaps be wrong, though, to make too much of the differences between ourselves and the Edwardians. Mitchell & Kenyon was involved in producing patriotic fictional reconstructions of scenes from the ongoing Boer war in which a terrorist enemy (which saw itself as a resistance movement) failed to abide by the rules. The era was also characterised by a widespread fear of immigration from Eastern Europe which caused the government to rescind its 'open door' policy for the first time, even though huge numbers of British were emigrating to Canada, Australia and the US, as M&K's films of dockyard farewells show.

Given Britain's current official anti-elitist approach to the arts and culture, it's hard to think of more appropriate artefacts to have uncovered. Here is an unparalleled source of regionally specific information about our great-grandparents' generation for today's visual age to consider. Like ours, this was a time of enormous social change that ushered in an era of populism. But mass culture was also a source of fear in a society much more stratified than our own, as described by John Carey in his devastating critique of modernist writers' hysterical reaction to the newly educated public in The Intellectuals and the Masses. "To highbrows," Carey argues, "looking across the gulf, it seemed that the masses were not merely degraded and threatening but also not fully alive... T.S. Eliot [in 'The Waste Land'] associates the crowds of office workers who swarm across London Bridge with the dead in Dante's 'Inferno'.

"A crowd flowed over London Bridge so many

I had not thought death had undone so many..."

Fully alive

The Mitchell & Kenyon films refute any claim that the clerical and industrial workers of the early 20th century were not "fully alive", but also bring to mind Eliot's lines for a quite different and more sombre reason. Engaged in a rearmament race with Germany by 1910, the UK embarked on militarising its population. And towards the end of M&K's active period we find military-preparation films along with parades of the 'pals' battalions of army recruits drawn from local factories and collieries.

We are reminded by these that the generation we've seen gambolling in front of M&K's cameras is precisely that flowering of home and empire that was virtually wiped out during World War I. In most of the acres of literature about the glorious long summers of Edwardian England – the past that, in L.P. Hartley's words, is "a foreign country" – we are called upon to regret the slaughter of the sons and daughters of middle-class families. But here we see men who join up almost joyously to escape the hell of noise and repetition that was the factory, the mill and the colliery. We see the spring in their step – and our knowledge of their eventual tragedy heightens the haunting quality of these films. Future generations, though, will be used to the idea of moving images of their ancestors. That particular sense of wonder is entirely ours.