Vera Drake

UK/France 2004

Reviewed by Ryan Gilbey

Synopsis

Our synopses give away the plot in full, including surprise twists.

London, 1950. Vera Drake (Imelda Staunton) lives with her husband Stan (Phil Davis) and their grown-up children, Ethel (Alex Kelly) and Sid (Daniel Mays). She works as a cleaning lady, and secretly performs abortions for girls in trouble. When one of her patients almost dies, the police call at her house where the family is celebrating Ethel’s engagement to Reg (Eddie Marson), and the pregnancy of Joyce (Heather Craney), Stan and Vera’s sister-in-law.

Vera is interviewed at the police station, where she is shocked to learn that her friend Lily took payment for booking the abortions. Prior to being arrested, she confesses her crime to Stan. Next morning, she is granted bail. Sid initially spurns her, and Joyce is reluctant to visit. At the trial, Vera is sentenced to two years and three months. In prison, she meets other women jailed for the same crime.

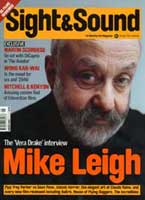

Review

Older audiences might let out a warm sigh during the moment in Vera Drake when the title character, a 1950s domestic whose twinkling eyes are buried in a doughy face like raisins pressed into a bun, retrieves a key from beneath a doormat. In his third period work (after the 1993 play It’s a Great Big Shame! and Topsy-Turvy from 1999), Mike Leigh proves himself adept at stemming the flow of nostalgia. Viewers who find solace in that key under the mat, or in the talk of bread and dripping, will be brought up sharp by the punishment doled out to Vera when it transpires that she has been performing illegal abortions. Her husband Stan is a mechanic whose work ethic is: "Bring ’em in, mend ’em, push ’em back out again." Not so different really from Vera.

The picture documents post-war English class prejudice as methodically as Fassbinder mapped out West Germany’s social and racial battleground in Fear Eats the Soul (1974). Class tensions manifest themselves in Leigh’s film in the contrast between Vera’s clients, most of whom undergo their terminations in squalor, and the experience of Susan Wells, a rape victim whose relative wealth, as well as her insider knowledge of the correct phrases to use in a psychiatric interview ("suicidal feelings", "madness in the family"), allows her a short stay at a bright clinic. The class divide is symbolised by visible barriers. A hospital screen, an IV stand, a staircase, a court bench - each cleaves the frame starkly in two.

The unifying factor is Vera, played by Imelda Staunton, who gets the kind of adoring close-ups, if not the wardrobe and hairdo, that a Hollywood star would kill for. She is frequently the only active element in a shot, scuttling between rooms filling teacups and emptying bedpans for incapacitated relatives and neighbours. Once she has been arrested, her stillness reverberates. With no further need to keep track of her errands, Dick Pope’s camera goes into a funk. Those constant chirruping offers of tea, which Vera seemed to make in every alternate line, dry up, leaving our ears parched. The mention of a hot beverage has never sounded so cruel as when it is made by a WPC unaware that she has assumed Vera’s defining function as bluntly as she has confiscated her wedding ring. Vera’s identity will follow. Leigh gives the movie her name, but in the final line of dialogue, which hurts like a stubbed toe, a prison warden reduces her to "Drake".

The film’s cleverest trick is to withhold for dramatic effect those elements that have grown comforting in earlier scenes. Vera’s absence from the family home, for example, is articulated when Leigh begins stinting on the tight, busy compositions that had previously denoted warmth and camaraderie. In those scenes set at mealtimes in the Drake household, he seems out to break some record for the largest number of faces squeezed into a medium shot. Once Vera is gone, the film must adjust itself to the change in temperament. Alone in her cell, she misses the old bustle, and so do we. When she is out on bail, Leigh stages an agonising Christmas dinner scene in which the camera cannot bring itself to capture everyone in a single tableau. Instead it takes in each family member individually during an extended pan round the room, just as Fassbinder did in that slow single shot in Fear Eats the Soul when Emmi announces to her vicious children that she has married Ali.

Like Fassbinder, Leigh uses the position and movement of the camera to underline the social implications of the narrative. He has made an exceptionally quiet film - Vera whispers her confession to her husband Stan in his ear, while those who felt battered by Leigh’s last film, All Or Nothing (2002), will be relieved to learn that it is nearly two hours before a raised voice is heard in Vera Drake. The camera expresses more anger than any slanging match.

An exceptional breadth of context and compassion is evident here, though the film is as much a triumph of production design as it is of acting, writing and direction. Eve Stewart has created a network of dimly lit passageways from which cramped doorways open on to sitting rooms where conflicting designs (floral patterns compete on the lampshades, wallpaper and curtains in Vera’s house) increase the claustrophobia still further. When the film has decamped to cells and courtrooms, the eye yearns for a return to that tangled chaos which the characters have made for themselves. There is no going back. The doors that have been open throughout the movie begin closing one by one - on a girl hospitalised by her violent reaction to an abortion, on Vera in her cell and again on Vera when she returns home and is snubbed by her son. In the last scene of Fear Eats the Soul, Fassbinder had the doctor close the door on Emmi as she comforted Ali in his hospital bed. Leigh leaves it ajar in the final shot of Vera Drake, framing the bereft family before using a simple piece of film language to express their emotional devastation - the fade to black, that door which no character may reopen.

Credits

- Produced by

- Simon Channing Williams

- Producer

- Alain Sarde

- Written by

- Mike Leigh

- Director of Photography

- Dick Pope

- Editor

- Jim Clark

- Production Designer

- Eve Stewart

- Music Composer

- Andrew Dickson