Changing The Guard

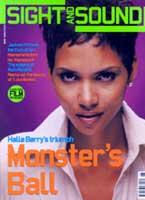

Halle Berry's Oscar made a dark and troubling movie an unlikely hit. Monster's Ball director Marc Forster talks to Nick Roddick

The Academy Awards were never really intended to reward innovators, let alone iconoclasts. Always an industry (as opposed to a critical or cultural) occasion, they were designed to reward those film-makers who tried just a little bit harder. Not so hard as to become uncommercial, of course - just hard enough to preserve the idea that Hollywood deals in both art and commerce. Cobbled together at the end of the 1920s to head off the Hays Office and incipient censorship by demonstrating that Hollywood could be all-American too, they have become a different kind of alibi: a self-congratulatory celebration of movies which don't wear their commercial ambitions on their sleeve. On their sleeve is the important bit here - all Hollywood movies are commercially ambitious. That's how they get made.

The big studios do all they can to ensure an Oscar through massive spending on advertising, which is not really as scandalous as it sounds - after all, no one complains about the studios using an advertising blitz to 'buy' a strong opening week. This year, though, most of the contenders were pretty much played out in box-office terms, and the traditional post-Oscar boost was largely restricted to one film: Monster's Ball, the only top winner not to be distributed by a major studio or affiliate.

Halle Berry's acceptance speech was the night's big headline-getter, but her tears were both understandable and eminently forgivable. Consider the figures: she was the first black woman ever to win a lead actress Oscar; her win and that of Denzel Washington trebled the number of African Americans who have won in the 'lead' category (their only forerunner was Sidney Poitier); and their wins increased by 50 per cent - from four to six - the number of African-American actors who have ever won an Oscar in the event's 74-year lifetime. All of which rather overshadowed the film (though it did add some $3 million to its box-office tally).

Like several previous Oscar winners, Monster's Ball is a film that struggled to get made. But Monster's Ball is no Forrest Gump (which languished in turnaround for nearly ten years). Whatever you may feel about its achievement - and it has detractors every bit as fervent as its enthusiasts - its story of a racist, white, southern prison guard who has a passionate sexual relationship with the black widow of a man he has just executed was never going to fit the classic one-sentence pitch. In fact, the above would probably have to be the one-sentence pitch, and it would be a foolish production executive who greenlit that in today's climate.The film's title apparently refers to a medieval English custom of throwing a drunken, final-night party for a condemned man, and the screenplay had been around Hollywood for six years before Lions Gate, an ambitious independent distributor keen to diversify, put it into production last summer. Monster's Ball was written by Milo Addica and Will Rokos, two actors who met while appearing in an off-Broadway production of a Sam Shepard parody called Fools in the West and discovered a shared history of childhood violence. "We wanted to do a story about breaking the cycle of violence that often your father imposes on you," Addica told a Los Angeles Times writer last summer. "We just didn't know how."

What gave them the clue was the discovery that the job of executioner in southern jails is often passed on from father to son. So the first part of their script focuses on the three-way relationship between widower Hank (Billy Bob Thornton), a senior prison guard; his father Buck (Peter Boyle), now retired from the death detail and living a bitter, oxygen tank-dependent life in the front room; and Hank's tormented son Sonny (Heath Ledger), who also works on the death detail. Sonny's suicide triggers the second half of the film, indirectly bringing Hank into contact with Berry's character Leticia, whose husband he has just executed and whose overweight son Tyrell (Coronji Calhoun) is killed by a hit-and-run driver. Every card seems stacked against these people.

Addica and Rokos finished the screenplay in early 1995 and wanted to set it up as an ultra-low-budget ($250,000) film they could direct themselves. Then Hollywood got interested. Over the next five years Robert De Niro, Tommy Lee Jones and even Marlon Brando were said to be linked with the project. Sean Penn and Oliver Stone flirted with the idea of directing. Lawrence Bender, Tarantino's partner, wanted to produce. With those names attached, the budget would have been way north of $20 million. But none of them wanted Tyrell to die. They wanted redemption - pretty much a Hollywood staple - but not from the depths that precede it in Monster's Ball.

Finally the screenplay ended up with Lee Daniels, who is actor Wes Bentley's manager and who saw Sonny as a great role for his client, then a very bankable commodity in the wake of American Beauty. He began talking to Mark Urman, head of feature production at Lions Gate, a company whose brave new slate had been dented by the premature 'rumour' that Leonardo DiCaprio would play the lead in American Psycho. Negotiations, which both sides freely concede were "a nightmare", dragged on for four months until Billy Bob Thornton came on board late last spring and Lions Gate agreed to make the film for the modest sum of $2.5 million. Thornton (and subsequent castings Berry and Boyle) agreed to defer their fees, which would otherwise have upped the budget by a factor of seven. In a final irony, however, Bentley, who had been through a nightmare of his own - the troubled Moroccan shoot of Shekhar Kapur's Four Feathers - backed out, suggesting as a replacement his Feathers co-star Ledger, the Australian actor who starred in last summer's minor hit A Knight's Tale.

Monster's Ball was shot on a 25-day schedule, which works out at an average of ten scenes - or four pages - a day. That, under those circumstances, it has such stylistic unity and assurance is, to say the least, impressive. There are no studio scenes - even the house interiors are those of real houses near or in the suburbs of New Orleans, with the execution scenes filmed in the actual death chamber of Louisiana State Penitentiary.

With the film completed, Lions Gate appeared uncertain as to how to position it, believing that Berry was not well known enough outside the US to carry it internationally and that pushing the other element which might attract feature coverage - the extremely impressive performance by rapper Sean (P. Diddy) Combs as Leticia's executed husband - would give the impression that this was a Dead Man Walking for African Americans. In the end, the film opened in time for Oscar eligibility, got into Berlin (where Berry prefigured her Oscar triumph by winning Best Actress), and recouped around ten times its production budget at the US box office, some 12 per cent of that in the week after the Oscars.

Monster's Ball is Swiss director Marc Forster's third feature. It would be nice to be able to say that its success surprised him, but I suspect it didn't. When I spoke to him the day after he had delivered his first, 140-minute cut of the film to Lions Gate last September, he seemed pretty well aware of what he had. "I will probably cut it down to 108, 110 minutes," he admitted then, "but even Lions Gate is saying, 'I don't know what you're going to cut here.'" Which is a nice - and distinctly unusual - thing for a distributor to say to a young director.

Forster - who is now in pre-production on the biopic Neverland, starring Johnny Depp as J.M. Barrie - was born in the ski resort of Klosters and gives a (possibly romanticised) account of a cinematically deprived childhood ending with an epiphany that launched him on his career path. "We grew up without TV," he claims, "and when I was about 12 or 13 I saw my first movie and just fell in love with film. When I graduated from high school, I found a benefactor who would pay for one year at NYU. Then, if I had any talent, he would pay for the second year."

Forster's talent must have been evident even then, because he spent three years at NYU Film School. He then made a couple of documentaries for Swiss television and the feature Everything Put Together, which premiered at Sundance in January 2001. "That's how I got this film," he says. "My agent gave me the historical background to the script - where it had been developed and who had been attached to it. I read it from cover to cover and it had an incredible impact on me because it captured so much of what's going on in American society without being a direct message film. Basically, it captured racism, the breaking of the circle of violence, so many different issues including the death penalty, without being preachy. The audience themselves can see the consequences and make their own decisions as to what's right or wrong."

At that stage only Bentley was definitely attached. "My agent passed the script on to Billy Bob," continues Forster. "Then I met up with him and we hit it off: we saw the film in the same way. After that Halle Berry got involved - she was so passionate and was such an interesting choice. Then I met several elderly actors and I thought Peter Boyle was just great. I always liked his work in Joe and other movies." The reference to John G. Avildsen's Joe, Boyle's breakthrough 1970 movie, is indicative of Forster's European background. Lionised in Europe (especially France), Joe - about a character who could easily be Monster's Ball's Buck 30 years earlier - is largely forgotten in the US. But there's another aspect of the new movie which fits snugly with Forster's background: the sense of a group of people living in isolation from the rest of the world. For all its totally different tone, the world of Fredi M. Murer's Swiss classic Höhenfeuer isn't so far removed. I didn't put this to Forster because it hadn't occurred to me then. But I did ask him about the sense of isolation and the fact that, although the setting is clearly contemporary, there's little to link the film to the third millennium.

"It's present day, yes, but you have a feeling that it could almost play any time," Forster says. "I tried to capture a timeless feel." This, he claims, was especially the case with Buck, whose racist reaction to Leticia hits the audience like a slap in the face. It's one of those 'did he really say that?' moments that precipitates the film's climax.

"It was very important that he wouldn't make the part one-dimensional," says Forster of his direction of Boyle. "For me, it's as if the character lives in a cave and is blinded by his surroundings when he emerges." Indeed, creating this sense of a world cut off from external realities seems to have been the key to the way Forster worked with his actors. "I try to create a sense of magic on set," he says. "People say directors should be dictators, but I see the director more as a magician. I try to create a sense of calm and a safe place for the actors, so they can go wherever they want and not feel judged or insecure."

The make-or-break of Monster's Ball is the scene in which Hank drives Leticia home, she invites him in, they get drunk and the relationship begins. It's almost certainly the scene that clinched Berry's Oscar - it's intense and uncomfortable, but with none of that sense of an actor's 'big moment' you so often find in Oscar-winning roles. Berry is out on a limb, especially since the first part of the scene consists mainly of a single, unrelentingly long take.

"The two characters have been so repressed and had so much tragedy in their lives, then suddenly - and she is a little more drunk than he is - they start expressing their emotions, their desperation. It's as if you open a bottle and everything just flows out," says Forster. "I think the scene is one of the most powerful I've ever witnessed. When I was standing in the room while we were shooting it, I felt like a ghost in someone's living room watching two real people. Even the script supervisor, who's done about 40 movies, just looked at me and said, 'God, I've never experienced anything like that before. That was very special.'"

I ask Forster, in one of those obligatory final questions, how he would describe what the film is about. "There are different ways to do it," he says, "but basically for me it's a story about tolerance and redemption - a cautionary tale about the price of complacency. And I like the feel of the ending. It's a true independent film, not some big studio blockbuster where you have to finish up the movie in a nicely tied knot. So I like the ambiguity, that not everything is resolved. You have a feeling that there's light at the end of the tunnel, but they're both not out of the tunnel yet."