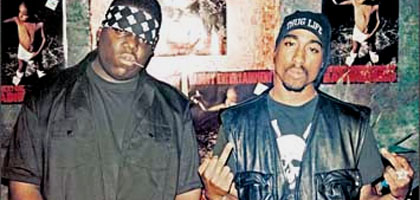

Biggie and Tupac

UK 2001

Reviewed by Ryan Gilbey

Synopsis

Our synopses give away the plot in full, including surprise twists.

A documentary in which director Nick Broomfield examines theories surrounding the fatal shootings of hip-hop performers Tupac Shakur and Christopher Wallace (aka Biggie Smalls, The Notorious B.I.G). Broomfield interviews various people involved with the cases, from ex-LAPD detective Russell Poole, whose investigation into Biggie's murder was stymied after he uncovered evidence of police involvement, to friends, family and witnesses, among them Tupac and Biggie's bodyguards and Biggie's mother Voletta. A theory emerges that cops moonlighting for Death Row Records - Tupac's label - were implicated in the shootings along with the label's co-founder Marion 'Suge' Knight, who is alleged to have orchestrated the assassinations to make them resemble gangland slayings. Broomfield visits Knight in prison, where he is serving time for parole violation, but Knight refuses to discuss Tupac's death. It is revealed that Voletta Wallace is now suing the LAPD for wrongful death.

Review

Documentarists such as Michael Moore, Jon Ronson and Louis Theroux owe an unpayable debt to Nick Broomfield and his aggressively intimate film-making style, which incorporates rebuttals, cock-ups and the interviewer's slightly bumbling on-screen persona. But in recent times Broomfield's work has been timid (Fetishes) or hateful (Kurt & Courtney), while it has made the heart sink to see this one-time subversive using his persona to flog cars in television advertisements. Happily, the weighty subject matter of Biggie and Tupac - an investigation into the killings of hip-hop superstars Christopher Wallace, aka Biggie Smalls, and Tupac Shakur - appears to have rejuvenated him. That might seem an odd word to apply to a film that is permeated by death, but the fact is that the screen is most alive when it seems most likely that Broomfield's interviewees, or even himself, will not be for much longer.

The film establishes a context for the killings: the public hostility between the East Coast hip-hop establishment, represented by Biggie and Bad Boy Records, and its West Coast counterparts, notably Death Row Records, co-founded by Marion 'Suge' Knight and home to Tupac, who at the time of his death was rumoured to be leaving the label. The evidence featured in the film points to the possibility of Suge's involvement, and the complicity of the LAPD and FBI, in both murders. Broomfield also touches briefly on the Black Panther roots of hip hop, LA gang warfare, and the controversy over Ice-T's track (with the band Body Count) 'Cop Killer'. Any one of these issues would merit its own documentary, but while they remain pertinent to the film's subject - the 'Cop Killer' scandal, for instance, was the catalyst for the FBI's surveillance of hip-hop performers - it is the personal angle which interests Broomfield, and which lends the film its immediacy.

Greying at the temples, Broomfield retains the manner of a public schoolboy diligently completing a homework project. He lugs his bulky recording equipment from the victims' childhood haunts to the homes of relatives and ex-cops, all the while deploying his best wheedling voice to put the screws politely on men who could stop his heart with a disapproving glance. This realisation releases sudden blasts of edgy humour. "You were knocking like you was scared, man," booms the huge bodyguard at whose apartment door Broomfield has been timidly tapping. In one scene, a pithy Death Row employee berates him for his 1995 film Heidi Fleiss Hollywood Madam. "The whole thing was to show how you was so slick," he complains, quite justifiably as it happens. When Broomfield makes an unscheduled and much discouraged visit to Suge in prison, he confers with the warden over the best way to approach this ogre for a chat; Suge has, after all, been advertised throughout the preceding 90 minutes as a murderer (as well as the man who once allegedly dangled Vanilla Ice by his ankles, which suggests he can't be all bad). "I don't mind asking him," says Broomfield, unconvincingly. "I'll put this down and ask him." Down goes the microphone. Nervous pause. "What do you think?"s he bleats to the warden.

This sense of jeopardy provides vicarious thrills from the comfort of the cinema seat, but it also creates a kind of corroboration. There is no possibility, after accompanying Broomfield through downtown Baltimore, where he is reprimanded by a sinister cop, or across a prison yard where his cameraman is too nervous to film the inmates, that we will doubt the plausibility of the movie's dreadful conclusions.

Even so, Broomfield leaves us not on this note of horror, but in the company of Biggie's crusading mother Voletta, who valiantly contests every scrap of accepted wisdom, including her son's self-mythologising claims of childhood poverty - claims that are as essential to the hip-hop genre as the violence that ricochets back and forth between street and lyric sheet. The "one-room shack" that Biggie sings about was actually a seven-room apartment where there was always food on the table, coos Voletta, a proud mother to the last. In this blood-curdling film, her words provide a moment of warmth, albeit one which will perhaps have Biggie cringing in his grave.

Credits

- Director

- Nick Broomfield

- Producer

- Michele D'Acosta

- Director of Photography

- Joan Churchill

- Editors

- Jaime Estrada-Torres

- Mark Atkins

- Music

- Christian Henson