Death's Cabbie

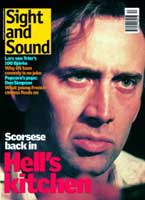

Their anger may have faded since Taxi Driver and Raging Bull but the director/writer team of Martin Scorsese and Paul Schrader have not lost their taste for seeking redemption in the New York night. In Bringing Out the Dead, "God's lonely man" is an ambulance driver played by Nicolas Cage. It's an intense, reflective, mature and musical return to favourite themes, argues David Thompson

"You Can't Put Your Arms around a Memory" (Johnny Thunders).

The first title comes up: "This film takes place in New York City." Then a second: "... in the early 1990s". Not the 1970s of Taxi Driver (1976), nor the 1870s of The Age of Innocence (1993). Bringing Out the Dead, based on Joe Connelly's recent novel, which is in turn based on his own experiences as a paramedic, is set resolutely in Martin Scorsese's favourite city, rarely moving beyond those hellish avenues west of Times Square and Broadway which Travis Bickle cruised in his checker cab. Twenty years on from Taxi Driver, the streetlife isn't much changed. The "whores, skunk pussies, buggers, queens, fairies, dopers, junkies" are still there, parading the sidewalks. But what appears to be Scorsese's first present-day urban film in a decade is in fact as much a historical document as Taxi Driver or The Age of Innocence, since Mayor Rudy Giuliani's clean-up has now transformed the area known as Hell's Kitchen (with more than a little help from the same corporation - Disney - that backed this film). After recreating the lost worlds of 70s Las Vegas and Tibet before the Chinese take-over, Scorsese the passionate archivist is at work again.

But is this enough to satisfy those who feel Scorsese no longer deserves the title of Greatest Living American Director? Since that tiresomely reiterated epithet derives mainly from his New York-based films (Mean Streets, 1973, Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, 1980), he has set himself a hard task here to match their intensity. And it would be wrong to suggest his new film possesses quite the burning anger of those masterpieces. But then again, both Scorsese and his screenwriter Paul Schrader, reunited after more than a decade, are now men in their fifties, with settled lifestyles far removed from those crazy years celebrated in Peter Biskind's Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. When Scorsese directed Mean Streets it was a spin on his own life experience; the same was true for Schrader when he wrote Taxi Driver. Jake La Motta coming close to screwing everything up for himself had a timely significance for both of them. Their new protagonist has concerns other than becoming Mr Big, cleaning up the streets or winning the title. And however troubled, heroes who want to live their lives on altruistic principles and find peace for themselves demand a different scale of movie. Perhaps the lesson of Kundun (1997) marks more of a departure than we might at first have imagined.

Nevertheless, from its first images Bringing Out the Dead has all the Scorsese trademarks, as the screeching harmonica intro of Van Morrison's 'TB Sheets' introduces an ambulance winging its way in front of us, followed by a red-drenched close-up of Nicolas Cage's staring eyes. In fact, this is the music Scorsese listened to back in the 70s when he thought of the opening shots of Taxi Driver. But there any comparisons should stop, because this is no psychopathic avenging angel at work. Cage is playing Frank Pierce, a lonely, insomniac paramedic on the EMS (Emergency Medical Services), haunted by the lives he has failed to save. The casting works well: the gentleness behind Cage's eyes and soft burr of his voice give credence to the innate goodness of the character. Straight away he's called to a cardiac arrest, who on first inspection appears to be dead. Suddenly the man's heart starts up, and they whisk him into ER, where his chances are pronounced slim (from six minutes after the heart stops, the brain begins to go, we're told), but he is kept alive. Frank becomes fascinated by the man's daughter Mary (Patricia Arquette), whose dazed, troubled demeanour matches his own.

Script and film stick close to Connelly's novel, and a first-person narrative finds its way into the familiar Scorsese/Schrader voiceover, though more sparingly applied than before. The film flips between the high-adrenaline charge of three wild nights on duty for Frank and the intervening two days when he spends quieter times with Mary. The effect is rather like two films running together, the first Scorsese at his most hyperkinetic. While rock music pounds away the director brings forth his full arsenal of visual weapons, with whiplash moves and dizzying camera positions sending the viewer headlong with the ambulance down those claustrophobic avenues, only a distant, narrow portal of sky offering any escape.

Each night links Frank with a different partner of increased craziness. The first, Larry, played by John Goodman with his familiar avuncularity, finds the necessary distraction from the surrounding mayhem in contemplating food. The second, Marcus, played by the cigar-toting, rasping soul brother Ving Rhames, has convinced himself that Jesus Christ alone is the arbiter of who lives and who dies. There's a hilarious episode where they are summoned to an OD and after Marcus obliges the would-be cool denizens of a goth rock club to join hands in an appeal to the Lord for deliverance the prone victim is jolted into life by Frank's unseen injection of adrenaline. The third, 'Major' Tom Wolls, played by a terrifying Tom Sizemore with full manic stare, is the most jaded of them all, meting out his own violent justice in the game of survival. By this stage Frank has turned to narcotic stimulation to make it through, and the frenzied, speeded-up images propel us to his final dealings with the death that surrounds him.

These sequences are a reminder of Scorsese's mastery in drawing the audience into the state of mind of his protagonists (think of Bickle's entrapment in his cab, La Motta's poundings in the ring or Henry Hill's cocaine frenzy in GoodFellas, 1990). Likewise, even the film's more reflective scenes encourage us to share Frank's need for escape, effectively winding down the pace to explore his attempts to connect with Mary. Unlike the cracking banter that keeps the paramedics up to pitch (and Scorsese and Schrader are as acute as ever when showing men at work), the exchanges between these two wandering figures move to a more hesitant, dislocated beat. The earnestness of Frank's solicitous gestures and Mary's air of distraction (she's a reformed junkie now feeling guilt about her father) function like separate lines of music in different keys. Elmer Bernstein's plaintive score here seems to have strayed from a 50s Elia Kazan movie (nothing too surprising about that; we know Scorsese's love for those films). Even Arquette's pleated dress, sweater and ponytail ("the night of the living cheerleaders," as she describes it) bring associations of a young Natalie Wood or Julie Harris being wooed by a halting James Dean. Arquette's wan manner has already come in for criticism, but it serves to depict a former drug user's slow emergence into daylight and her reluctance to admit that she may have a real connection with Frank.

Scorsese has been criticised too for filling his film with music - a tough call for the director who virtually invented the rock soundtrack in mainstream cinema (inspired, as he has made clear, by Kenneth Anger's Scorpio Rising). Bringing Out the Dead has some great choices, contrasting ecstatic soul from Martha and the Vandellas and the Marvelettes for the Marcus scenes with the blasting energy of the Clash for the rides with Tom Wolls. If there's one surprising miscalculation it's the 10,000 Maniacs accompanying Frank and Mary sitting side by side in the ambulance, the constant bumps eventually obliging her to look over to him - the music sentimentalises a subtle, pensive moment, while Thelma Schoonmaker's editing, cutting away sharply from Arquette's sudden smile, tells it all.

What engages us is not just the play of sound and the visual punch but also Scorsese's skill at comedy. There's abundant black humour in the Emergency Room ('Our Lady of Mercy' becomes 'Our Lady of Misery') - it's just as much of a rollercoaster of exasperation and hysteria as any we've seen, with the distinctive additions of a sententious cop who refers to himself in the third person and whose ultimate threat is the removal of his dark glasses and a seen-it-all nurse who works on what vestiges of guilt remain in her patients. Scorsese himself and Queen Latifah supply the voices of the gutsily comic radio dispatchers. But it's not just a question of sharp dialogue and well-tuned performances. There's a continuous thread of irony in the scenes where Frank comes face to face with would-be suicides. The recurring figure of Noel, a volatile junkie whom Frank calms down with the not-to-be-fulfilled promise of a comfortable death in ER, functions throughout as an out-of-control taunt to the role of the paramedic as saviour of lives. Frank's confusion lies in trying to comprehend why the rules of survival are being constantly rewritten - why should a junkie live and a new-born baby die?

Of course this is just the arena where Scorsese has thrived, placing his films far from the tidy moral requirements of Hollywood. And it's the quality of ambiguity that makes Bringing Out the Dead a fascinating journey. In some respects it's a ghost story as Frank is constantly haunted by the apparition of Rose, a young junkie whose face appears among the crowds as the nights become more intense. When Frank escorts Mary to the Oasis, the apartment of neighbourhood drug dealer Cy, he agrees to take a pill which unleashes in his mind a string of fantastical images. The streets flash by in a frenzied blur, and then in slow motion human arms emerge from the ground, with Frank pulling them out one by one. The visual echo here of the casting-out-of-devils sequence from The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) cannot be accidental, for Frank is becoming consumed with the idea that just as lives should be saved so must souls be allowed to depart the physical world peacefully. (As if to underline the sacrificial nature of this gesture, Scorsese slips on to the soundtrack a distorted fragment from the final dance of Stravinsky's 'The Rite of Spring'.) The fateful encounter with Rose is then staged by the meat market, with the surrealist touch of hanging ribs of beef in the snow overlooking the scene where Larry and Frank fail to prevent her death.

From this moment on the film becomes ever more hallucinatory, with Frank slipping further and further into a dream state. In the hospital Frank hears the voice of Mary's father telling him he wants to die, and when Frank finally relieves the sick man of his life he does so not just by pulling out the tubes that keep his heart beating but transfers the wires from the EKG monitor on to his own body (the fact that he already has the electrode patches in place under his shirt begs the question of how far we are slipping into his delusional state). Here the film departs sharply from the novel, in which Frank is accused by Mary of killing her father and then returns home believing that Rose is there to comfort him. In Schrader and Scorsese's version Frank subsequently visits a becalmed Mary who for an instant becomes blurred with Rose, repeating the medical mantra: "You have to keep the body going until the brain and the heart recover enough to go on their own." How far Frank has really found her acceptance or is now living within his own fantasy Scorsese leaves open, much as he did Rupert Pupkin's solipsistic triumph in The King of Comedy (1982) or Travis Bickle's public vindication in Taxi Driver.

The look of Bringing Out the Dead is a departure from these earlier films - with Robert Richardson, the cinematographer who came to light mainly through his collaboration with Oliver Stone, Scorsese has shifted gear from his previous work with Michael Chapman and Michael Ballhaus. While Chapman (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull) gave Scorsese grit and a bold range of colours and Ballhaus (GoodFellas, The Age of Innocence) gave him speed and richness, Richardson is more a man of high contrasts and daring camera moves. The wild, speeded-up scenes are something we haven't seen before, and yet are brilliantly integrated as only Scorsese seems to know how. The white light that bathes the ER (something of a Richardson trademark ever since the glowing hands and blanched-out spectacles of Stone's JFK) suggests the presence of a benign healing spirit, possibly an angel of mercy. In Cy's apartment the tableau-like framing and sickly pink decor (courtesy of Dante Ferretti) underline the oneiric atmosphere (there's more than a hint of David Lynch's Blue Velvet here). In what has already become one of the film's most celebrated sequences - when Cy is speared alive on a railing after falling from his apartment and has to be cut loose with torches while Frank holds him - the cascading sparks dissolve into an imaginary fireworks display, evoking a strange epiphany ("When the fires start to fall, then the strongest rule it all. I love this city").

Epiphanies, angels of mercy, the search for peace in death. The Christian religion - and specifically Catholicism - has always been inextricably part of Scorseseland; even Kundun had an emphasis on blood that seemed to have seeped in from the Christian ritual. When Frank arrives at the violent aftermath of a shooting at Cy's apartment, the first image is a river of blood mingling with the water from an exploded fish tank. The very liquidity of the colour red gives this sequence a mesmeric quality, especially as it's accompanied by the reggae version of 'Red, Red Wine' by UB40, rendered sinister by association. But what's curious about Bringing Out the Dead is how far the Christian context is less to the fore than might be expected (even the statue of the Virgin in ER, complete with neon halo, is usually out of focus). Both Schrader and Scorsese have confessed to moving on from a time of overwhelming preoccupation with Christian dogma to widening their sense of what the spiritual might entail. True, the final scene is a kind of pieté, with Frank softly resting his weary head on Mary's breast as an intense white light breaks through the window. But is this not also simply the morning sun, accompanied by the first birdsong we've heard since the opening titles? It's tempting to read this as a Bressonian moment of grace, but are we witnessing a direct parallel to the French master's depiction of God's spirit made manifest through the natural world or something in the mind of the protagonist alone? If Frank really has found his redemption, it seems more a case of a human, rather than divine, touch.