Digital Deluge

Low-budget digital film-making is here to stay and some directors love it. But what are the consequences for British cultural films if DV is the only option? Nick James asks five film-makers, one writer and a Film Council funder if it really is 'Digital or Die?'

When Sight and Sound, in collaboration with the Film Council's New Cinema Fund, organised 'Digital or Die? - the Future of Film', an eight-city roadshow debating the possible consequences of the coming of digital film-making, we wondered what reception we might get, not only from audiences but also from our collaborators. Given the properly sceptical stance of our editorials about the future of British cinema, S&S is hardly the NCF's natural ally and indeed there was some tension at first between the fund's keen desire to publicise its new collaborative scheme with regional film boards to produce 100 cheap digital shorts each year and our wish to test the aesthetic and democratic impact of the digital revolution.

On the opening night in Cardiff there were ructions. 'This is an insulting television commissioner's approach to cultural film funding', thundered irate documentary film-maker and academic Brian Winston, the panel's appointed digital sceptic. Nevertheless, the tension proved productive, and the audience, a high proportion of whom were film-makers, engaged fully with the arguments. The roadshow's focus was deliberately narrowed to two themes: is DV a more democratic medium in that it allows all film-makers the chance to make films whatever their circumstances, and is DV too weak in terms of depth of field, the sharpness of the image and the representation of movement to be an adequate aesthetic substitute for the swirl of grain and the flicker from the projector that make 35mm such a medium for magic? The one aspect of the tour that shocked this writer was how little so many people who want to be film-makers seem to care about the way their films look. It's as if they just want to tell stories, and see film-making as a less onerous and more glamorous method to do so than writing a book.

Yet many of the most interesting and engaging of our panel members were practising film-makers. And this led us to dream up a final summit, a discussion that would pinpoint the crucial themes and try to develop them further. To this end we brought together several film-makers at the coal face of the digital revolution at the Edinburgh Film Festival. Their biographies appear on page 24.

Each roadshow event began with an opening speech that set out three conditions which make the move to digital film-making in Britain almost inevitable. First, the main sources of funding in the UK seem determined to make movies of international popular appeal rather than movies about the way we live in Britain today. Second, the glut of bad lottery-funded movies means exhibitors are reluctant to show expensive celluloid British films. Third, since the NCF, now the only source of UK funding for cultural cinema, is very enthusiastic about digital, digital is per se the only route to go. The conversation below kicked off after a similar introduction.

Chris Cooke In Nottingham everyone I know either has a video camera or regularly hires or borrows one. When the Dogme manifesto came out, some people were yawning and saying, 'We've been doing that for ages', while others were saying, 'Fantastic, now we can carry over what we've been doing into features.' There's a fluidity to the DV process, from filming through to distribution. People know it's within their means and audiences pick up on the documentary immediacy. It's more instantaneous, more familiar aesthetically.

David Mackenzie It invites a different way of making a film. The characters are more human.

Chris Cooke On my New Directors' short Shifting Units the actors used to want to play back what had been shot at the end of each day. I was thinking, 'I'm not supposed to let them, in case they say 'it looks wank'.' But the moment you get into the editing suite it looks fluid. It's because the shots are rawer.

Billie Eltringham What's exciting is that you can do it fast, without lights and much cheaper. I don't have to stop the performances because the grips have a problem. All these advantages are appealing, but it doesn't look great. But then I asked myself, is there anything about this that's not trying to mimic film that makes it more interesting? Are there things only DV does, like when you let something in the foreground go really soft and the colour has a weird leak-out effect?

Nick James So you're feeling your way into a new language?

Billie Eltringham Yes, and we don't know what it is yet. We're inventing it as we go along.

Kate Davis The huge benefits are the ease and the intimacy. On my documentary Southern Comfort it was very important to be in a one-to-one situation with the people in the film, to be able to strip it down to just myself as the crew with these people who were open sexually and falling in love while one of them was dying. It was very intense stuff and I don't think it would have had the immediacy if I'd had to deal with switching stock magazines. One-hour DV loads rather than 10-minute film loads make a big difference. But I'm also frustrated by the way it looks. There's nothing more beautiful than celluloid on the screen - I'm that kind of snob. I set out to make something that looked like a theatrical film and I shot it accordingly.

Saul Metzstein I'd like to challenge some of the assumptions emerging here. I made Late Night Shopping on film and I'd argue that it's not always better to shoot quickly. If you shoot slowly, you may need only three shots for a scene where somebody shooting faster might use more shots because it's easier. There are certain types of film-making that suit shooting very slowly, particularly films involving complicated art-department work. Second, the look of DV is changing all the time. We'll have the same discussion in five years' time and none of us will be able to tell the difference between something shot on film and something shot on video. Third, there's an overwhelming tendency in British culture to analyse things in literary rather than aesthetic terms. You can see it very obviously in reviews for Sight and Sound which tend to concentrate on story rather than shots, partly because that's the dominant viewpoint and partly because it's easier to talk about stories than aesthetics.

Billie Eltringham Often one is at the expense of the other. If you want to be realistic it can be embarrassing to say you also want it to look nice.

Chris Cooke A single shot can be fantastically well composed, but surely with DV the composition is in the editing? I was watching John Cassavetes' A Woman under the Influence, a film that would work equally well on DV, 16mm or 35mm. It's not about composition, it's about the way the camera chases Gina Rowlands around.

Paul Trijbits Let's ask three questions of the film-makers here about why they chose digital. First, was the decision purely financial? Second, was it because you would have total freedom to do what you wanted? Or third, was it because you wanted to create a different aesthetic?

Billie Eltringham Having come from 35mm into digital for This Is Not a Love Song I'm going straight back to 35mm. It wasn't a matter of budget - Simon Beaufoy had an idea which we thought would be interesting to do on DV. It was a chase film, a two-hander, and we thought we could find a different, very fast way of telling the story. We also wondered how cleanly our voices would emerge if we didn't have to ask anybody for permission to shoot the script. It didn't end up exactly like that, but that was the idea.

Paul Trijbits Could you imagine having done that film in the traditional way - developing the script, raising £2.5 million, shooting on 35mm and maintaining complete control? In the end you made it in 12 days for £500,000.

Billie Eltringham Part of the interest for me was my feeling that DV is coming whether we like it or not, so I wanted to explore it aesthetically and in a way get there first.

Saul Metzstein It was suggested, in that fashionable way, that we make Late Night Shopping on DV, but it wouldn't have worked for that particular film. For instance when you choose your lighting set-up it's not just for DV or 35mm but because you want a certain aesthetic which for us was as important as the story. So the choice was between spending £200,000 on shooting on 35mm or dealing with an unacceptable level of graininess. Interestingly, in our Dogme documentary Thomas Vinterberg said he made the story of Festen so melodramatic because he thought he would then get away with the digital aesthetic.

Nick James Did anyone go digital because they had to?

Kate Davis With no funding and very little time, grabbing a camera and shooting was the only way for me to go. But most documentary film-makers are used to limitations; all kinds of compromises take place or you miss the moment. What you get from working within limitations is the chance to explore how far you can push them. I was able to do with DV certain things I couldn't have done on 16mm and you could say that added to the aesthetic - you hear intimate stuff, camera movements are much easier, especially jumping in and out of cars, and scenes could develop with more integrity than with a crew and a film camera. I love the look of 16mm, but I think I might have missed a lot if I'd used it on this project. So I'm a bit of a DV convert. When I look back at some of the great vérité films I'm amazed at what they captured.

David Mackenzie We got funding for The Last Great Wilderness from Scottish Screen on condition it would be digital and that was the right decision. In fact, the way the project evolved it could only have been done on DV because we decided to throw the story to the wind. There were five weeks of madness - we shot 120 hours of footage knowing that 90 per cent of it would go into the bin.

Paul Trijbits The experiment with This Is Not a Love Song was terrific because the whole thing took only four months, from treatment to completion. But I'm worried now that everyone will come in and say, 'Don't worry about the script or the budget, we'll just shoot it on DV.'

Chris Cooke With the script I'm working on at the moment potential backers are saying, 'If you're going to use improvisation, could you at least outline every single thing to be improvised?' It's not a bad thing because it means you have to think.

Nick James One of the reasons the New Cinema Fund is so gung-ho for digital is because at some point we're going to have to find a different way of distributing cultural films. What might that be?

Paul Trijbits At the Bristol roadshow I saw a little e-cinema - a room with low benches and a big white screen and they plugged in a laptop and that was it. The quality was astounding. But I'm worried that nobody is thinking about how DV films need to be projected.

Kate Davis It de-democratises the whole process if you have to blow up a cheaply made film to 35mm. SM There's a double standard in operation here. What we watch on video or DVD are 35mm films that have been transferred, which is something people have done beautifully for a long time. There isn't necessarily a linear connection between the medium you make a film in and the medium in which it's broadcast.

Nick James But since cinemas aren't showing British art movies and cultural films, surely there has to be a different method of access?

Billie Eltringham It's like going to the pub on Saturday afternoon to watch a game of football. When you're sitting on your own at home it's not the same - you'd rather have a bigger screen and be with your mates. It would be nice if we felt the same about film. I think the solution might be smaller venues where we could watch the quality English stuff we used to see on television.

Chris Cooke The people at the cutting edge of digital film aren't interested in distribution to multiplexes or arthouses or to big open spaces where the audience sits on the ground. They get their work on to websites and people tell them what they think of it. The far end of democratisation is that everyone can afford a DV camera and every town has an edit suite and people will post their edited films on the internet and then there'll be 54 million films made by 54 million film-makers. And each will be seen by only one person.

Kate Davis Statistically it would seem there ought to be more strong films if more people had access to the technology, but I'm not so sure. I was on a jury recently at which we were asked to talk about how great DV is, but all the panel members, including myself, acknowledged that this easy technology can cloud your vision. You think more carefully before you press the button on a film camera than you do on a DV camera and that's no bad thing.

Paul Trijbits If everyone has their own camera and we get Chris' horror story of 54 million films it isn't going to help any of you.

Nick James But that's the global capital model. I attended a discussion in Rotterdam two years ago with a lot of music people and what the entertainment corporations want is exactly Chris' idea - people eating their own products. You produce the stuff and consume it in loops. That concerns me because film for me is an artform and web movies are mostly not.

David Mackenzie We tried to be as amateur as possible on our film. I had to fight the crew to stop them being professional. I needed to find the material, to have it evolve in its own way and to shoot it in lots of different ways so it could be created in the edit suite because I wasn't comfortable with the script.

Paul Trijbits But you're an accomplished film-maker who knows how to do things in the traditional way - what to point the camera at and how to tell a story. To be 'amateur' for you was a choice.

David Mackenzie No more storyboard logic - let's throw it to the wind and see what happens. One of the great hopes for the creative future is amateurism.

Nick James I don't believe that. When I look at many current British films I see a lot of poor craft. Take the recent adaptation of Martin Amis' Dead Babies. It was pitched at the level of a school play.

Billie Eltringham Simon Beaufoy can write something sharp in six days but we'd have got a very different script for This Is Not a Love Song if we'd asked someone who hadn't written a film before. And I wouldn't have wanted to shoot a feature in 12 days if I'd had no previous experience.

Nick James British films of the last couple of years often show a disregard for the screenplay, which is something the Film Council has picked up on.

Paul Trijbits That's because people were jumping from a sexy 10-minute short to a £3 million feature. Not only has the FC picked up on that, putting money aside for the development process, but the New Cinema Fund is doing the same thing. We're looking for ways for people to be original and it's better to do that with £500,000 than with £3 million. Films in that bracket made in the last two or three years have lacked craftsmanship, experimentation and commerciality. (None of the people at this table have been involved in that kind of project.) It's so bad that if you go out today to sell a £3 million British film, neither America nor any major European territory wants to touch it.

Nick James And if you go higher you need movie stars.

Paul Trijbits Yes. But there are distributors out there looking for cutting-edge, pushing-the-boundaries material and they don't care if it's shot on black-and-white film, DV, DVC pro or 16mm. What they don't want is people doing things in a very traditional manner.

Nick James What would you say doing a digital feature has taught you?

Billie Eltringham Our DoP Robbie Ryan said it made him look at natural light again because we used no lights and hardly any reflector boards. It made us look at what was already there before we started lighting. PT Robby Müller, who shot My Brother Tom, which the Film Council part-funded, hates DV because he says you have to light it in the same way as 35mm. We had a bunch of night sequences and we thought we'd just be running around with a camera but there was Robby putting lights everywhere. He says that aesthetically digital gives a heightened kind of camerawork but if you just put the DV camera where you'd put your 35mm camera, you're missing the point.

Nick James So to sum up, what are the advantages of DV?

Kate Davis It's easy to carry, you can shoot for a long time, it's cheap.

Billie Eltringham It's made so you can have a crew all looking in the same direction.

Chris Cooke It's liberating to be able to say, 'Let's try this, let's try that', and to keep working until you've run out of steam and then to move on to the next scene. Then to sit in the editing suite weeks later and be surprised how much footage you have to cry over.

David Mackenzie I'm not a total convert, but I'm glad to have done it and hope to do another.

Richard Kelly The interesting thing for me is the possibility of politically radical content. The unencumbered nature of the technology allows you to do riskier things. At Edinburgh we've seen Haskell Wexler's Medium Cool, handheld, 16mm, a great American film that sent actors and cameras on to the streets of Chicago during the anti-Vietnam riots at the Democratic Convention in 1968. You could have done the same thing with the anti-G8 demonstrations in Genoa. You can do a politicised fiction film in a much simpler way.

Saul Metzstein I'm more interested in aesthetics than technology. If DV's better for certain things, then great.

Biographies

Chris Cooke's latest film Shifting Units, a digital short made under the bfi's New Directors' scheme about a man nearing breakdown as a result of his addictions and the pressures of his job, gained a special mention at last year's Edinburgh Film Festival. He is currently developing an anti-buddy movie focusing on the empty lives of four drinkers.

Kate Davis worked in television before completing her first documentary Girl Talk in 1988. Her latest documentary Southern Comfort, about a transgendered man who develops cancer and his girlfriend, won a Grand Jury prize at the Seattle International Film Festival and will be shown at the Sheffield Documentary Festival in October.

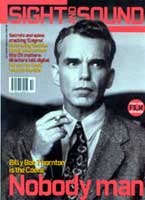

Billie Eltringham's work includes co-directing Physics for Fish with Simon Beaufoy. Her latest feature is This Is Not a Love Song, a digitally shot thriller set on the Yorkshire moors.

Richard Kelly's study of the Dogme film-makers, The Name of This Book Is Dogme '95, was published in 2000. He also wrote and presented the associated documentary, directed by Saul Metzstein.

David Mackenzie works mainly in television, writing, directing and producing short films and features. His digital short Somersault was broadcast last year; he is currently completing The Last Great Wilderness.

Saul Metzstein has worked on short films, features, adverts and documentaries, including The Name of This Film Is Dogme '95. His feature debut Late Night Shopping was released in June.

Paul Trijbits is head of the New Cinema Fund at the Film Council.