Rough justice

Film of the Month: Pledge, The

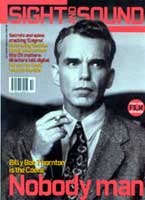

A bleak thriller, The Pledge confirms Sean Penn's worth as a director. By Richard Kelly

[Editor's note: the following review necessarily reveals significant plot points

The fraught relationship between crime and its shadowy double, justice, has inspired a few great writers, as well as a horde of fairly mediocre ones. But given the ceaseless public appetite for tales of cop versus criminal, it's no surprise that sometimes a kind of literary stewardship takes place, whereby a fine specialist respectfully appropriates the themes of a genius, and renders them in slightly more accessible form. Much as the late Patricia Highsmith modelled her fictional explorations of guilt on 'the master', Dostoyevsky, so the Swiss novelist and dramatist Friedrich Dürrenmatt offered his readers a racy revision of Kafka.

The womb of all Dürrenmatt's work might be Kafka's famous parable of the law from The Trial, wherein justice is seen as eternally elusive to those who most ardently seek it. Dürrenmatt's sequence of slender, existential detective novels, such as Der Richter und sein Henker/The Judge and His Hangman (1952) and Das Versprechen/The Pledge (1958), are fables that toy with the genre, in order to indulge the author's pet themes: the helplessness of man against insatiable evil, and the impossibility of avoiding moral contamination in the act of revenge. Often grisly in detail, these novels are leavened nevertheless by a keen sense of comic irony. It's in a kindred spirit of mischief, perhaps, that Sean Penn describes his new film version of The Pledge as 'a 'no-good-deed-goes-unpunished' tale'.

Superficially, this is Penn's most mainstream work as a director to date, dealing as it does with a detective's efforts to trap a serial murderer of little girls, having sworn a vow on his 'soul's salvation' to a grieving mother. Commercially and critically, The Pledge has enjoyed a rather less grudging reception than Penn's previous directorial outings, Indian Runner (1991) and The Crossing Guard (1995), but it's a different breed of beast in several key respects. For one, the screenplays of those pictures were Penn originals, and very characteristic of the man himself in their high levels of naked, earnest emotion. So, although Miramax tried to sell The Crossing Guard on its elements of gunplay and suspense, Penn was at pains to point out that he saw the piece as 'an anti-thriller, an anti-revenge movie': a study of how grief and guilt may be at least partially salved by kindness and forgiveness.

The Pledge, however, is not a novel that offers much solace to the tender-hearted. It was brought to Penn by his producing partner Michael Fitzgerald, and it was reckoned as a solid property upon which to reunite Penn with his friend Jack Nicholson, whose soulful performance anchored The Crossing Guard. Screenwriters Jerzy Kromolowski and Mary Olson-Kromolowski accordingly translated the action of the novel from Zurich to Nevada; and to Penn's great credit, his film is laced with Dürrenmatt's unmistakable mood of cosmic corruption and fatalism. (Assisted by DoP Chris Menges, who conjures up a succession of gracefully sombre natural landscapes, Penn even manages to emulate Dürrenmatt's care for the slow turning of weather and seasons.)

Penn has been true to the novel's contours in all but one respect. Dürrenmatt's narrative is encased within a sly framing device, his narrator (a lugubrious crime writer) sharing a sodality with an old police chief, Dr H, who instructs him as to why true crime is so much more infernally complex than fiction. By way of example H recounts the debacle suffered by his 'most capable man', one Inspector Matthai, whose patiently wrought plan to catch a child-killer with 'live bait' was undone by a simple twist of fate, the killer himself was killed in a car wreck en route to the scene of the sting. Hence H's - and Dürrenmatt's - rueful lesson: 'The only way to avoid getting crushed by absurdity is to humbly include the absurd in our calculations.'

Implacably Penn reels us towards the same terminus, working as ever with editor Jay Cassidy, and pacing his film with total assurance. His Matthai figure, Nicholson's Jerry Black, is morally skewered by his pledge to murdered child Ginny Larsen's pious mother (Patricia Clarkson). While his colleagues readily accept a barely coherent confession extracted from a retarded man (Benicio Del Toro), Black pursues other ominous clues, such as Ginny's crayon sketch of the 'porcupine giant', a tall dark man bearing little prickly gifts. We can see that Jerry wants to be righteous, but Penn steers us to the discomfiting realisation that his best intentions are leading him unwittingly into evil, as when he befriends roadhouse waitress Lori and draws her daughter Chrissy into his design to catch the killer.

In Dürrenmatt's novel, Matthai has scant feeling for this mother and child, and states his intentions quite plainly to H, who ponders before asking, 'Isn't that rather a devilish scheme?' Yet both men are hooked, in a manner so unseemly as to make for a kind of complicity in the original crime. Penn, though, has Jerry Black keep his own counsel, and so we are left to make our own judgement on the basis of Jack Nicholson's superbly controlled performance. We are, at least, encouraged to think well of the fondness Jerry lavishes on Chrissy (Pauline Roberts) and the fledgling intimacy he shares with Lori (the hugely affecting Robin Wright Penn).

Still, Penn also makes us suffer in ways even Hitchcock might have shied away from. Late in the novel, H halts the narrative to suggest how his awkward story could be converted into the simpler stuff of a hit movie. Playing to his friend's penchant for cruel denouements, he proposes that Matthai might pursue the wrong man, perhaps 'some sectarian preacher with a heart of gold' who 'would attract every shred of suspicion the plot has to offer'.

Penn duly invents just such a character, Gary Jackson, cloaks him in the sinister trappings of Ginny's 'porcupine giant' and casts towering actor Tom Noonan, previously the homicidal 'Tooth Fairy' in Manhunter (1986). Such troubling touches help to make The Pledge's final reel an authentic experience in dread, flaying both Jerry's nerves and ours. (Possibly we don't deserve the queasy sequence in which Jerry races to Jackson's chapel, throws open its doors, and, for one horrendous instant, imagines Chrissy crucified on the altar.)

In the end, Jerry is still chasing these phantoms when his real nemesis, the barely glimpsed 'Wizard', crashes and burns. So, while Jerry's ex-colleagues and his surrogate family desert him in mingled pity and revulsion, Penn's camera zeroes in on the Wizard's roasted, blackened corpse at the wheel of his flaming sedan. Is this the torment of the damned, or just another cosmic joke about the anonymity of evil? Either way, Penn then deposits us back where we began in the film's opening moments: Jerry, sun-baked and rotten with booze, rocking on his heels outside his lonely gas station, conducting an angry dispute with himself. The main musical theme, glacial and shivery when first heard over the opening credits, now grows percussive and exultant. Resistance is useless, senselessness has triumphed, and the camera ascends to leave Jerry stranded, a natural fool of fortune.

Penn has confessed elsewhere that The Pledge is 'a retirement-crisis story disguised as a thriller. I didn't get the retirement-crisis story financed, if you know what I mean. But I got it shot.' The result is a brilliant achievement, albeit one that finds Penn flexing only selected sets of his creative muscles.

He is 41 now, wholly committed to a directing career, and yet it's taken him a full ten years to get three pictures under his belt. It's possible that in a further decade's time, if he has built the body of work he aspires to, then The Pledge will be viewed as a film that he made largely because he could. But there's no harm in that. (Orson Welles made his Nazi-hunting thriller The Stranger, 1946, just to get back on terms with RKO; even Cassavetes set about The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, 1976, hoping that he might benefit from the vogue for gangster movies post-Godfather.)

The Pledge is an elegant rejoinder to a tired genre, a consummate work of screen adaptation, and further evidence that there is precious little Sean Penn can't achieve on film, whether before or behind the lens.