Boys' Own Stories

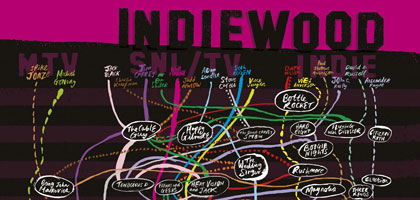

Some call it Indiewood, some the Frat Pack: a prolific American generation of comedians and wry auteurs. Here Henry K. Miller plots their progress.

The great wave of Indiewood cinema broke over the UK in just a few months, with Wes Anderson's Rushmore and Alexander Payne's Election arriving in late summer 1999, David Fincher's Fight Club that autumn, and David O. Russell's Three Kings, Spike Jonze's Being John Malkovich and Paul Thomas Anderson's Magnolia following in early 2000. Since then a slew of articles and books such as Sharon Waxman's Rebels on the Backlot, James Mottram's The Sundance Kids and Peter Biskind's Down and Dirty Pictures have recounted the moment when these mavericks "took back Hollywood".

Many of them had emerged from Sundance in the mid-1990s and they shared that elusive 'indie sensibility' even as they moved into studio production; there were rumours that, like the much-mythologised Movie Brats of the 1970s, these guys hung out together. All this led to a consensus that the young directors were "self-conscious heirs to" (Waxman) or "spiritual descendants of" (Mottram) the New Hollywood. The comparison, and the self-consciousness, were almost inevitable since the rebels arrived on the backlot at the peak of 1970s retro - in music and fashion as well as in film culture - with Biskind's Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, arguably the most influential film book of the last decade, appearing in 1998.

Wrapped up in this (re)valuation of the New Hollywood, and reinforcing the notion of Indiewood as 'revival', is a repudiation of the 1980s in terms of both politics and aesthetics. "When the Ronald Reagan tsunami swept everything before it," declares Biskind, "the market replaced Mao, the Wall Street Journal trumped The Little Red Book, and supply-side economics supplanted the power of the people." Likewise for Waxman, 1980s Hollywood was all "loud music, fast-paced editing, and sexy women: the cultural equivalent of junk food". Mottram, meanwhile, charges the rise of the event movie with nothing less than "the dumbing down of world culture".

If the influence of the Movie Brats is freely, even eagerly, admitted by the Indiewood auteurs themselves, this revival narrative blocks out the ugly truth that the movement's creative resources lie as much in the fallen age that followed 1980's Heaven's Gate as in the golden years that preceded it. Neither Spike Jonze nor David Fincher, with their backgrounds in music video and advertising, betray an obvious debt to the New Hollywood, and indeed the high-concept action cycle apotheosised by Jerry Bruckheimer and Joel Silver is the clear starting point for Fincher's early features, whatever his destination. Nor are these the only black sheep in Indiewood's line of descent.

Mutant cinema

"I meet people who say, 'When I go to the movies I don't want to think. I think all day at work. I just want to let go and enjoy myself, so I put on an Adam Sandler movie.' I try to be patient but I have contempt." (Alexander Payne, co-writer, I Now Pronounce You Chuck & Larry, 2007)

The mythology of the 1970s is not just about the movies, but addresses a generational experience - of Nixon-era despair and disillusionment thrown on to the screen, but also of newfound entitlement for film as a medium. "For a few years it was all one could do to wait for the next startling picture," wrote David Thomson in an essay symptomatically titled 'The Decade When Movies Mattered'. "In colleges, people studied film history and foreign films. In bookstores, film was a new section. Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris were at their best. Repertory theatres were thriving." Indiewood lacks this complementary backdrop, and the movement, such as it was, was not so much short-lived as spread very thin, with its leading lights never appearing hungry for work.

Moreover, when the Class of 1999, none of whom had shone at the box office, returned three years later, "it felt," says Waxman, "like the studio's siren song had crept into the consciousness of the young directors." If Panic Room (2002) saw Fincher reverting to type, what was Paul Thomas Anderson doing working with Adam Sandler? Punch-Drunk Love (also 2002) won plaudits, but Anderson's film was (surely?) a diversion before he returned to more respectable fare - a prospect amply fulfilled by 2007's There Will Be Blood. The phenomenon of lowbrow comedians turning legit is nothing new, but the meshing of Anderson's authorial fixations with Sandler's self-described "shy moron" persona was uncanny.

In truth, the traffic between Indiewood and the tradition of sketch comedy associated with Sandler's alma mater Saturday Night Live had been running both ways for some time. Original Sundance Kid David O. Russell, seeking to tap a similarly neurotic vein for his neo-screwball Flirting with Disaster (1996), had gone to the mat with Miramax to cast SNL alumnus Ben Stiller (fresh from a pally cameo in Sandler's Happy Gilmore) in the lead. The exchange continued in the other direction with Sandler's Anger Management (2003), in which Tom Charity identified "the hysterical panic - Sandler taps into, buried down beneath the neutering constraints of political correctness, the - suppressions and anxieties of the new man, the strictures of therapy culture." As well as kidnapping P.T. Anderson regulars John C. Reilly and Luis Guzmán, the film saw Sandler delve improbably into Fight Club or Magnolia territory: this was mutant cinema.

Stiller's Indiewood liaison did not end with Russell. When the suits claimed that Wes Anderson's Bottle Rocket (eventually snuck out in 1996) had garnered some of the worst test-screening results in the studio's history, its co-author and star Owen Wilson claims to have weighed up joining the military before Stiller stepped in to cast him opposite Jim Carrey in The Cable Guy (1996). Produced by Sandler's erstwhile flatmate Judd Apatow, The Cable Guy now stands as the prototypical Frat Pack comedy, seven years (give or take) ahead of its time, its cast rounded out by Leslie Mann and Jack Black. And in its thematic concerns, Stiller's film anticipates much of what would distinguish the Indie-wood auteurs from their 1970s predecessors.

Halls of mirrors

Apatow and Stiller had first teamed up while making The Ben Stiller Show in 1992. Consisting almost entirely of parodies-cum-tributes to TV, movies, advertising and pop videos, the show demanded that its viewers share its makers' obsessive level of pop-cultural literacy. A hall-of-mirrors affair, its best running joke, in which Stiller 'as himself' tries to suppress a 'close-to-the-bone' video diary of his 'real life', is also a nicely self-reflexive comment on the show's limitations, which it shares with the early work of many of the Sundance Kids. Epitomised by Quentin Tarantino, this was a cultural moment, as Ian Penman said, for "people who can spot pop-trash references the way people used to spot wildflowers and lapwings."

The very first scene of the embryonic Bottle Rocket, shown at Sundance in 1993, consisted of an in-depth discussion of an episode of Starsky and Hutch by the film's two leads as they made their way towards a robbery; Spike Jonze's video for the Beastie Boys' 'Sabotage' the following year drew on the same source, at once sending up and celebrating the 1970s cop show. Meanwhile Charlie Kaufman's last job as a TV writer before Jonze took on his Malkovich script was on an SNL spin-off series, The Dana Carvey Show (1996), which like Stiller and Apatow's show was largely made up of parodies and impressions. (Future Apatow collaborator Steve Carell was another member of the writing staff.) Though hardly the Rosetta Stone of Kaufmanology, a skit about 'being' John Malkovich while he orders hand-towels as a life-changing experience would not have been out of place.

Stiller intended The Cable Guy to break this cycle of intertextuality, reflecting at the time that "you get to a point with parody where you can't go much further because ultimately it's feeding off somebody else's creativity." His villain, the titular cable-installation guy Chip (Carrey), is the embodiment of 1990s postmodernity: everything about him from his name down is taken from television and the movies. Chip could be The Ben Stiller Show's ideal viewer - or its author. Channelling similar anxieties in a comparable form, The Cable Guy now resembles Fight Club in negative.

The protagonists of the two films - Fincher's unnamed narrator 'Jack' and The Cable Guy's Steven - are white-collar types whose relatively comfortable if ennui-laden lives are disrupted by a psychotic alter ego. But whereas Fight Club's Tyler Durden counsels physical self-destruction, scorning material comfort, Chip is an agent of media saturation. Less explicitly phantasmal than Tyler, he alternates between involving Steven in dangerous fantasy scenarios, derived at random from Hollywood or television, and trying to cocoon his newly single quarry in a 'home entertainment system' that monopolises his home.

Bobby Dupea, Harry Caul and Travis Bickle - the anomic antiheroes of the New Hollywood - are only distantly related to Jack and Steven's cohort; indeed, when these icons of the 1970s are invoked in Indiewood and Frat Pack movies they represent a boomer generation thoroughly at ease with its own egotism, with Jack Nicholson and Gene Hackman giving lessons in self-actualisation to the nebbishes Sandler and Stiller in Anger Management and The Royal Tenenbaums (2001). The common experience of these 'middle children of history' is not so much isolation as insulation, their spiritual home neither the mean city streets nor the open spaces of the American interior but Jack's "filing cabinet" of condos, Paul Thomas Anderson's San Fernando Valley. Nominally a comedy, The Cable Guy is shot, like Fight Club, as a thriller with a supernatural edge, the look of Steven's apartment inspired by Polanski's horror films.

Released at the pinnacle of the late-1990s boom, Fight Club turns around to satirise Tyler's Nietzschean-macho-bullshit antidote to the ills he diagnoses in consumer capitalism, with Jack realising that "all of this, the gun, the bombs, the revolution" is a kind of displacement activity - like Steven and Chip's absorption in pop culture - keeping him from committing to the film's other lost soul, Marla. Like Tyler and Jack, and like Barry in Punch-Drunk Love, Steven and Chip belong to Tyler's "generation of men raised by women", with Chip claiming that "I never met my father, but the old TV was always there for me."

Reversing a longstanding cultural syndrome that associated mass entertainment with femininity, it is the men in Apatow's films who are pathetically in thrall to pop ephemera, with women focused on - scare-quotes - the important stuff. If, as actress Katherine Heigl has said of Apatow's Knocked Up (2007), this means it tends to be the male performers who get to be funny, some of the film's best scenes - the argument between Debbie (Leslie Mann) and Pete (Paul Rudd) over Spider-Man 3; Alison (Heigl) kicking Ben (Seth Rogen) out of her car - pivot on exactly this disequilibrium. Like later Apatow protagonists, The Cable Guy's Steven learns to put away childish things and patch it up with his ex, exorcising Chip in the process. Tyler's question "if another woman is really the answer we need", dealt with ambiguously in Fight Club, is given a full-throated 'yes' in Apatow's romantic comedies, whose male protagonists have to beat off not rival suitors but - like Jack, like Barry - their demons.

As its producer has had time to reflect, "a Jim Carrey movie that ends with his suicide attempt was a bit of a risk", and The Cable Guy was a notorious flop. While Apatow returned to television, Stiller and Wilson formed a partnership that took Wilson some distance from his original ambitions as a writer. Though he co-scripted Rushmore and The Royal Tenenbaums with Wes Anderson during these years, by the time he and Stiller appeared together in Tenenbaums and Zoolander in autumn 2001 Wilson had managed to parlay his character from Bottle Rocket into the Hollywood mainstream, effectively 'writing' the lion's share of the parts he has taken on. Bringing Will Ferrell - yet another SNL performer - to big-screen prominence, Zoolander marked the zenith of the Stiller-Wilson double-act. Its DVD cult status was recently augmented by an endorsement from Terrence Malick - a bizarre version of Scorsese's famous boost for Bottle Rocket, but no less deserved. The mercurial Wilson's insouciance towards distinctions between 'respectable' and 'lowbrow' cinema in these years was at once salutary and suggestive of their underlying affinities.

Performance art

"I'd never gone to the mat for another director's film that way; I'd go up to people and tell them, 'Listen to me. You cannot go wrong with this.

Will Ferrell is the next comedy guy. I am a comedy snob, and Will Ferrell is sublime.' And they wouldn't fucking do it! They'd say it was too weird, they didn't get the comedy." (David O. Russell, executive producer, Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy, 2004)

The resemblances between The Cable Guy and Fight Club were not down to personal connections between their makers or to direct influence, but to some more diffuse generational synchronicity. Nonetheless, the comedic tradition Carrey, Stiller and Apatow had all been schooled in flowed through Fincher's film. With its rituals and para-situationist pranks, Tyler's 'Project Mayhem' is as much fraternity as terror cell, and Fincher himself has cited National Lampoon's Animal House (1978) as inspiration, Bluto duking it out with Jake La Motta for paternity rights. Edward Norton has characterised the film's controversial second half as "so obviously about what goes wrong when a bunch of frat boys start taking themselves too seriously" - and much the same is true of the film that gave the Frat Pack its unfortunate name, Todd Phillips' Old School (2003).

Reviving the National Lampoon-SNL tradition, Phillips' film concerns the struggle between a rowdy fraternity and the university authorities, only this time the frat has been set up by three guys in their 30s who are either dissatisfied with married life or, in the case of nominal protagonist Mitch (like Steven in The Cable Guy), working through a break-up. Phillips called Old School "a comedy version of Fight Club" and numerous scenes are clipped directly from Fincher's film. Mitch's path back to adulthood follows Jack's, or Steven's - but by that point both the frat and the film have been hijacked by 'Frank the Tank', the signature role of third-billed Will Ferrell. Accepting divorce with equanimity, Frank embraces his regression, finally taking over the - college itself. In this version, Tyler lives... and so a subgenre was born.

Old School enabled Ferrell and co-writer/director Adam McKay - supported by David O. Russell, then at work on I [Heart] Huckabees - to make Anchorman, the film that also announced Judd Apatow's return to feature production, eight years after The Cable Guy. Based on extensive pre-production cast rehearsals and improvisation, and drawing on a gifted pool of comic performers, Anchorman established the Apatow modus operandi, what Russell calls "a balance between performance art and narrative film". Only Zoolander rivals it for this decade's most quoted movie.

Apatow had spent the interval in his film career producing two of the best-loved and least-seen television shows of the last decade, both of them cancelled after a single season: the incomparable Freaks and Geeks and the campus sitcom Undeclared. Gathering together a team of talented young actors and writers, Seth Rogen chief among them, Apatow also enlisted between-work feature directors like Jake Kasdan - who had made the excellent neo-noir Zero Effect (1998) with Ben Stiller - and Greg Mottola, whose debut The Daytrippers (1996) was an indie of the heroic maxed-out credit cards/ trust fund/family friends variety. One of a dying breed, it was nixed by Sundance and sandbagged by Miramax, then entering its imperial phase.

His success with The 40 Year Old Virgin (2005) and Talladega Nights (2006, again with Ferrell) allowed Apatow to put his protégés to work again, with Mottola taking on Superbad (only his second feature) and Kasdan Walk Hard: Dewey Cox. Apatow's latest hiring, for the stoner action-comedy Pineapple Express, represents perhaps the most surprising career turn since Punch-Drunk Love: David Gordon Green, whose debut George Washington (2000) was another Sundance reject. (Green's abandoned Confederacy of Dunces, planned for Ferrell, is one of the decade's great what-ifs.) There's no reason to assume cynicism in these strange affiliations - along with its structural similarities to his earlier film, Mottola's Superbad is as finely observed as The Daytrippers - and the Apatow phenomenon could be seen as a kind of 'New Indiewood', just as the first wave disperses.

Tracing Wes Anderson's falling off into preciousness to the end of his writing partnership with Owen Wilson underlines how far the relationship between the accredited Indiewood 'mavericks' and their 'lowbrow' contemporaries was mutually enriching while it lasted - and how bogus, held too firmly, the distinction between them can be. While some of the gusto for the - culture wars which Alexander Payne and Jim Taylor brought to Citizen Ruth (1996) surfaces in their screenplay for I Now Pronounce You Chuck & Larry, Sandler's film suffered from a comparable form of the paunchiness that afflicted Payne's Sideways (2004). Trapped, like Anderson, in circumscribed relationships with their respective audiences, - neither Payne nor Sandler seems now capable of the teen-comedy sit-in that was Election or the alchemical high of Punch-Drunk Love. Against this gloomy prognosis for the old guard, Russell's next feature will, we're promised, "do for Washington, D.C., what Talladega Nights did for race-car driving." Here's hoping!

See the print edition of Sight & Sound for more on the fratpack: Kim Newman traces their ancestry back to the 1950s via National Lampoon's 'Animal House' and 'Saturday Night Live', Edward Lawrenson interviews Noah Baumbach about 'Margot at the Wedding'and Ben Walters explores 80s nostalgia and a love of amateur film-making in Michel Gondry's 'Be Kind Rewind' and Gareth Jennings' Son of Rambow