Bite of the living dead

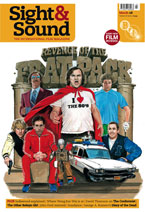

Film of the Month: Diary of the Dead

Kim Newman celebrates a new flesh-eating zombie movie from director George A. Romero that resurrects the premise of 1968's Night of the Living Dead within the ongoing horror movie that is 21st-century America

George A. Romero's Night of the Living Dead (1968) changed the look, tone, pace, production methods, release patterns and critical reception of horror films. A vision of society collapsing as the dead rise, influenced by Richard Matheson's novel I Am Legend and a slew of films from Invisible Invaders (1959) to The Birds (1963), Night of the Living Dead launched a sub-genre of flesh-eating zombie apocalypse pictures. When Romero made the follow-ups Dawn of the Dead (1979) and Day of the Dead (1985) he triggered new waves of imitative efforts - including 'answer' films like Lucio Fulci's Zombi 2 (1979), positioned in the Italian marketplace as a sequel to Dawn of the Dead but finding its own pulp identity in the UK as Zombie Flesh Eaters, and Dan O'Bannon's Return of the Living Dead (1984), a loose adaptation of a novel by Night co-writer John Russo intended as a follow-up to the original. Even the imitations had imitators, sequels and spin-offs.

Night was among the first 'modern' horror classics to be remade, with Romero himself scripting Tom Savini's 1990 Night of the Living Dead (though he carefully had nothing to do with 2006's Night of the Living Dead 3D). Yet it took the near-simultaneous arrival of Zack Snyder's Dawn remake and Edgar Wright's parody Shaun of the Dead in 2004 to remind the industry that Romero was still available for work, prompting the writer-director to return with Land of the Dead (2005), which extended his epic vision to a post-apocalypse world peopled by some recognisable star names.

In the meantime, dozens of zero-budgeted projects have dragged zombie feet over the same ground - from the pioneering shot-on-film The Dead Next Door (1988) to video efforts like The Stink of Flesh (2004). After the compromises of making Land for a major studio (Universal), Romero has gone independent for Diary of the Dead, which rewinds the plot back to the starting point of the first film (each entry in the series begins with the recent end of the old world, with no direct link between them) and competes directly with the Blair Witch-inspired film-makers whose output often seems little better than the clumsy mummy movie would-be director Jason Creed is shooting as the film opens.

Diary of the Dead arrives after The Zombie Diaries, a British effort that takes a similar video-diary approach, and The Ghouls and Feeding the Masses, both of which also focus on the unhelpfulness of the news-media during a flesh-eating crisis. It's possible that Romero has a magisterial unawareness of the waves of activity in his wake - and while his film is savvy about the patchwork nature of today's mass media (it even tries to show where footage edited into Jason's film comes from), its real inspiration seems not to be some direct-to-DVD zombie quickie but Haskell Wexler's Medium Cool (1969). A speech about people stopping at an accident site to gawp rather than help evokes the climax of Wexler's film, which has often been linked (along with the finish of Easy Rider) to the ironic-horrific reverse at the end of Night.

While many film-makers have taken the suspense mechanics, gore or panicky-nasty characters of Night as models, its satirical social commentary, which reappears here, remains Romero's own. The director himself cameos in Diary as a police chief lying on television about an early zombie incident, with news footage that slants the story to minimise the living-dead angle, and throughout there's much Medium Cool-style debate about the way the media manipulates and mangles the truth and the combination of prurience, egoism and altruism that drives those who photograph real-life horror.

Jason Creed, a lead character necessarily off screen most of the time, sets out to counter mainstream media lies but can't help but impose his own equally skewed vision, at considerable personal cost (not only do most of his friends die during the making of his film, but so does he - arguably, twice). It's typical of Romero's humour that Diary should begin with the shooting of a feeble mummy movie, where an actress argues against horror clichés (the torn dress to provide nudity, the stumbling creature who ought to be easy to escape), then climax with the same principles in play as the scene unfolds 'for real' and Jason carries on filming rather than intervening to help.

Diary may initially struggle to get up to speed as it reprises business from the earlier films, but Romero has lost none of his wild inventiveness. This film has more left-field weirdness and edgy suspense than Land, with unexpected characters (a deaf, dynamite-throwing Amish farmer), grim jokes (the zombie birthday clown who bleeds when his red nose is pulled off) and horror scenes you have never seen before (in a crowded, gloomy warehouse, amid reserves of gasoline, a single, hard-to-find zombie mingles with jittery, well-armed folk). It turns out that despite decades of experiment, there arestill spectacular new ways of killing zombies on screen (a slow acid-dissolve of the skull), while presenting state-of-the-art make-up effects vérité-style recalls the impact of the gruesome intestine-gobbling scene in 1968.

It's hard to tell when Romero is kidding. The hard-drinking British film professor Maxwell emerges as a comic creation more suited to Shaun of the Dead, with his pseudo-profundity or quoting from Dickens provoking perhaps unintended giggles. This taking Maxwell lightly mutes powerful moments, as when Debra thanks him for disposing of her zombified loved ones. The mostly young and attractive student crowd are in line with typical horror-film disposables, though even among this fairly privileged group Romero still finds an interesting range of social classes and attitudes. The more naive characters believably act as if they haven't seen such movies before and have to come to terms with the necessity of shooting their former friends or recognising that the support services are unlikely to help - snippets of news footage make this a post-Katrina rather than a post-9/11 movie.

In the coda - a YouTube home video of rednecks amusing themselves by shooting zombies - Romero revives the Vietnam-era violence of Night but also evokes new horrors such as Abu Ghraib or Guantánamo. The Dead films are the director's own take on the rolling apocalypse of modern American history - and the real chill of Diary is that his vision is as biting now as in 1968.