Primary navigation

Since the 1960s, film-makers have revisited the Great Depression in search of America's nomad soul - the intrepid loner, forging his own future. Michael Atkinson wonders whether gangsters are at the heart of the American Dream

Since the 1960s, film-makers have revisited the Great Depression in search of America's nomad soul - the intrepid loner, forging his own future. Michael Atkinson wonders whether gangsters are at the heart of the American Dream

There was a time, as recently as the mid-1990s, when few thought to put a label on the fantastically homely, sincere, thorny, sometimes haywire but most often scorchingly rigorous US movies of the Nixon/'Nam era - the American New Wave - and to consider it a bygone cultural moment unto itself. A latecomer to the New Wave party, the American school largely arose from a primordial-ooze cocktail of social protest, youth-culture empowerment, international cinephilia and prole restlessness. But almost universal amid the five o'clock shadows, unlovable losers and frontier highways was a sense of America itself - it was not merely Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper in Easy Rider who searched for their nation's nomad soul, but the protagonists of hundreds of films, whether or not they seemed to know it.

America was suddenly, as the toxic reality of the Vietnam involvement sank in, a mysterious territory we'd lost while daydreaming with Eisenhower and Kennedy, in a swoon of post-war materialism and conformist depression. This is why there were so many aimless, metaphoric road movies in the 1967-77 period - you don't drive with the boys in Monte Hellman's Two-Lane Blacktop without a socio-existential itch to scratch - and why the films paid such careful attention to landscape, even or especially if the horizons were largely comprised of supermarkets, junkyards, empty gin mills and industrial provinces on the verge of collapse.

Other, related impulses also revealed themselves in that era: disaster movies revelled in the utter inadequacy of authority figures, and a disarming fascination with the moral compromises of middle age became ubiquitous. But the short span of the New Wave in the US was also the moment when nostalgia became a national obsession. Though every decade from the 1950s and earlier became eulogised and exploited, none was as lovingly recreated or as physically explored as the 1930s. Beginning more or less with Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and running through Bloody Mama (1970), Sounder (1972), Paper Moon (1973), The Sting (1973), Emperor of the North Pole (1973), Chinatown (1974), Thieves Like Us (1973), Bound for Glory (1976), The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings (1976), among many others, the trend cast a soft-focus, tweed-and-Model-A nimbus over the otherwise tense and confrontational 'Nam era.

Was it just escapism in an unlikely package? How did this happen, the youth-dominated, counterculture-doped 1960s segueing so suddenly into an avid jones for the America of 40 years prior, with its starving migrant workers, booming hobo demographic, desperate range families, ancient patois and unpaved roads? (Following the rough 20-year-lag pattern of retro trends, the revisiting of the 1950s in American Graffiti, Happy Days and Grease was far more predictable.)

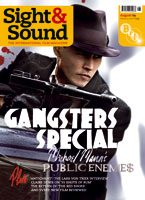

Oddly, while other Nixon-era ideas have long faded, the 1960s-70s conception of the Depression period has persisted in the popular forebrain - Michael Mann's Public Enemies is merely the latest reincarnation of that reincarnation, iconicising the tommy-gun-and-fedora mode that merely passed for sensational realism in the 1930s, just as the occasional gangbanger drama does today. Woody Allen, Martin Scorsese, the Coen brothers, Guy Maddin, Abel Ferrara, Ron Howard, Lars von Trier, Sam Mendes, Gary Ross and scores of other film-makers have gone to mythical 1930s in recent years, tending to balance any revisionist brio with idealised daydreaminess. The popular portrait of the Depression today resembles less a catastrophic economic ordeal than a cultural childhood, remembered through roseate mists (or brooding urban fog) and bathed in spring sunshine.

We rob banks

Outlaw violence was in fact hair-raisingly prevalent in the US at the start of the 1930s, and the infrastructure required to hunt and capture serial-killing criminals was still finding its footing. But, of course, the 1960s movies hyperbolised the situation, for fun and profit, in groundbreaking ways. Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde shocked audiences with its counterpoint of familiar overacting and frank bloodletting, daring us to sympathise with genuine sociopaths (as differentiated from, classically, Nicholas Ray's hard-luck innocents in They Live by Night, nearly 20 years earlier). Its success gave birth to scores of imitators, including John Milius' Dillinger (1973) and one of Roger Corman's most enthusiastic bandwagon-jumping sprees, comprised of not-so-dirt-cheap renditions of The St. Valentine's Day Massacre (1967), the Barker Gang story (1970's Bloody Mama), the fictional hobo autobiography of Boxcar Bertha (1972) and Capone (1975), plus a number of fictional helpings of pure Corman pulp.

The St. Valentine's Day Massacre restricted itself to re-enacting the documented minutiae of the Capone-Moran conflict in gruelling flow-chart style, and as such it still feels like a bout of back-lot dress-up, even for Jason Robards' snarling Capone. Yet generally Corman gave full vent to the baloney legends that had circulated about the gangsters in the tabloids - many doubtless manufactured by J. Edgar Hoover in order to make the culprits scarier to the public at large. And it's difficult to imagine that anyone would favour the true story of Ma Barker - who abetted her four sons in their bank-robbing/kidnapping career but was otherwise a dull-minded bystander - to what Corman gives us: incest, sadism, dope addiction, homicidal matter-of-factness and Shelley Winters commanding the terrain like a mother gator eating her way to the queenhood of the swamp. Bloody Mama would be yowling matinee dross if it weren't so focused on the characters (including Diane Varsi's embittered sex toy, Robert De Niro's grinning junkie, Don Stroud's psychopathic bad boy and Pat Hingle's fearless kidnapping victim), and if it weren't so filled with earnest Method actors.

As it was, the idyllic vision of the Depression captured in the 1970s had everything to do with economics, as Corman understood perhaps best of all - in the Nixon years there were huge portions of the southern and midwestern US that hadn't changed appreciably in 40 years, having been left out of the post-war development loop by virtue of sheer poverty and neglect. Conveniently, if not coincidentally, these were the same states and regions that many of the gangster-era crooks used to prowl, giving film-makers ready-made locations that were both authentic and inexpensive. (Even today, a drive through large poor parts of Louisiana, Arkansas and Virginia will evoke a sense of time travel.) It's not chance that many of the Depression movies made in the 1960s and 1970s, gangster or otherwise, take place in the overheated, hazy South - as if the Depression occurred only there - or that a generation of Americans grew up thinking of the 1930s as a soft-focus time of overgrown meadows, dusty back roads, sharecropper shacks and faded gingham dresses.

The searchers

The gangster figure, of course, has always been a source of contention. In the 1930s, heroic portrayals by James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson were quickly turned on their head due to public outcry, while in the noir epoch gangsters were generally portrayed as venal power brokers capitalising on the social gaps left by the war and post-war opportunities. But the gangsters of the Capone-Dillinger years were consistently revisited, often with little attention paid to period detail or accuracy, and always played as sociopathic rogues or simple mercenary capitalists exploiting what was increasingly viewed, with the passing of years, as a lawless, almost anarchic time in recent history.

In the 1960s, starting with Arthur Penn's Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, the gangster became instilled with the new era's antihero glamour; we were supposed to suspend judgement on them because their antisocial mayhem was framed as an individualistic reaction to an unjust world. Psychopathy was suddenly an illness inflicted on the unfortunate. This makes the characters kissing cousins to the very first Cagney-Robinson hoods, beloved by audiences for their defiance, audacity and contempt for ideas of redemption - and destined for a rain of bullets by movie's end.

In fact, prizing amoral independence over the social code is as American as prairie rockets and moonshine, even if most of us cannot dare to simply knock over a bank and then disappear into the flatlands like a ghost, preferring instead to watch other, less rational rebels gamble with their freedom. The Depression-era gangsters were in their own ignorant way searchers - in a sense, critic Robert Warshow was right when he famously defined the gangster as “the 'no' to the great American 'yes' which is stamped so big over our official culture and yet has so little to do with the way we really feel about our lives”. But were Barrow, Barker, Dillinger et al genuinely seeking an alternative to America, or just looking for the same elusive nation later hunted by the Easy Rider cast, and an entire contemporaneous generation of hippies, folk singers, communalists and dropouts?

It's small wonder, actually, that the Depression swatch of history seemed so attractive to Americans caught in a flux between the stabilised society they were supposed to rely upon after World War II, and the rollercoaster of upheavals they endured instead. Looking back at the 1930s, the frontiers still seemed open, the country still had vast regions where the feds and the taxmen did not tread, and an outlaw could still try to remake the New World according to his or her own desires. Men roamed the territories by the millions, off the grid and without mortgages or cars, looking for answers to their most basic questions. Certainly, albeit in the 'Nam years under more affluent and therefore philosophical circumstances, the generational need to rediscover a lost idea of ourselves dominated the culture, and the Depression proles were our brothers. Get some money some other way than working for the Man, hang out in a found farmhouse, live in the moment getting high and outside sociosexual restrictions - what could be more gangster-like or hippyish? Bonnie and Clyde was certainly the first time in movie history we saw notorious 1930s desperados frolic in an open field, like a pair of Berkeley sophomores.

Not every nation troubles itself about 'what it means', but America routinely does, having been artificially defined not so long ago and been thoroughly compromised ever since. Only in America is ideal community sought by heading out alone on the open road, and outlaw freedom seen as an integral ingredient to a strong society. The nostalgia-spawned gangsters, along with innumerable New Wave bikers, wanderers and scroungers, had to die by the last reel not necessarily because crime doesn't pay, but because that's where the search leads them - to where the seductive contradictions come to a graceless dead end.

Many of the films mentioned in this special feature screen as part of the 'Gangsters' season at BFI Southbank, which runs throughout July.