Primary navigation

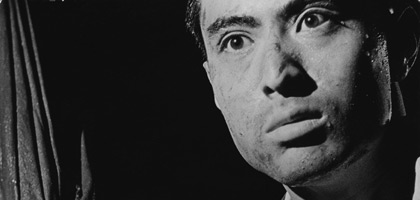

Best known in the west for the period co-productions In the Realm of the Senses and Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence, Oshima's finest works are the fiercely modern Japanese films he made in the '60s, says Alexander Jacoby

Half a century since Oshima Nagisa's career as a director of feature films was launched with A Town of Love and Hope (Ai to kibo no machi, 1959), he seems more than ever a figure from the cinema's past. Oshima himself is still living, albeit in poor health, but it is a decade since the release of his last film, Gohatto (1999), which itself was his first fiction feature since the mid-1980s. Many masterpieces from his best period, the late 1960s and early 1970s, remain unavailable on commercial DVD; for many, the current travelling retrospective will be the first opportunity to see them. It is a paradox that this film-maker, who ruthlessly charted the post-war Japanese experience, is now best known for two late films realised with foreign funding, and in some ways atypical: In the Realm of the Senses (Ai no corrida, 1976), an explicitly erotic film about a 1930s couple who retreat into a private world, and Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence (1983), a humanist study of the relationship between British and Australian soldiers and their Japanese captors in a prisoner-of-war camp during World War II.

It is another paradox that Oshima, whose films are the manifestations of a deliberate and uncompromising modernism, today seems more distant than Ozu, who has been dead for nearly 50 years, and who was the archetypal representative of a now defunct Japanese studio system. Perhaps Ozu's work requires less in the way of contextual knowledge: arguably, contrary to the traditional formulation, it is Ozu who is the least Japanese of Japanese directors, or at any rate, the least distant from western experience. His style may have an understatement which is alien to the conventions of western cinema, but his concern with families struggling to raise children, make ends meet and cope with change is fairly universal. Oshima's films, on the other hand, demand a fuller understanding of his place in the history of Japan and the history of cinema.

Internationally, 1959 was a watershed year in film history. In France, the release of and critical acclaim won by François Truffaut's The 400 Blows (Les Quatre cents coups), shortly to be followed by Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless (A Bout de souffle), marked the moment when the nouvelle vague became a force to be reckoned with. Oshima's feature debut A Town of Love and Hope appeared in November of that year, and he soon became associated, along with other young directors such as Shinoda Masahiro and Yoshida Yoshishige, with a parallel movement, the nuberu bagu (a transliteration into Japanese of the French term). For a brief period Kido Shiro, the formidable head of the Shochiku studio, hoped that cheaply made, innovative films by younger directors would recapture an audience being steadily lost to television.

But in Japan, 1959 also marked a political watershed. That year saw the first protests against the renewal of the US-Japan Security Treaty. By 1960 these escalated into mass demonstrations: a scheduled trip by US President Eisenhower was cancelled for fear of his safety, and Japanese Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke was obliged to resign - though the agreement was, nevertheless, eventually renewed. Against this turbulent background, Oshima made his first films, which already, in their focus on delinquent youth, gave voice to the tensions in Japanese society.

These two developments, one aesthetic and one political, met in Oshima's fourth feature, Night and Fog in Japan (Nihon no yoru to kiri, 1960), in which the director essayed a scathing satire on the disunity of the radical left. Within days of the film's release Asanuma Inejiro, leader of the Japan Socialist Party, was assassinated by a right-wing fanatic. Shochiku, convinced that Oshima's film was inciting civil disorder, pulled it from cinemas, an event that was a central factor in the director's departure from the company.

Throughout his career, Oshima remained a provocateur and iconoclast. He focused on those excluded or marginalised by Japanese society, from the Christian martyrs of the 17th century in The Rebel (Amakusa shiro tokisada, 1962) to the ethnic Korean minority of modern Japan in Three Resurrected Drunkards (Kaette kita yopparai, 1968) and Death by Hanging (Koshikei, 1968). Many of his protagonists are criminals: his debut feature A Town of Love and Hope and 1969's masterly Boy (Shonen) both dramatise the experiences of children forced into crime. The protagonists of Violence at Noon (Hakuchu no torima, 1966) and Death by Hanging are murderers, and Oshima portrays their crimes as a response to the oppressive structures of Japanese society. This proposition was most illuminatingly examined in Death by Hanging, a scathing critique of the death penalty, which expressed Oshima's opinion that “As long as the state makes the absolutely evil crime of murder legal through the waging of wars and the exercise of capital punishment, we are all innocent.”

Breaking the mould

In retrospect, it's impossible to imagine that Oshima could ever have been comfortable at Shochiku. His subject matter was too close to the bone, and his contempt for the established conventions of Japanese cinema too profound, for him to work successfully at the studio which more than any other had defined the style of Japan's classical cinema. Maureen Cheryn Turim's book on Oshima is subtitled Images of a Japanese Iconoclast, and Oshima himself has commented that “My hatred for Japanese cinema includes absolutely all of it.” Oshima's own works usually present themselves as self-conscious departures from convention, breaking both with the expectations of the industry - traditional narrative patterns, established genres and the star system - and with the style of earlier Oshima films.

Ozu is an auteur in the traditional sense: one whose style and themes are reiterated with sublime consistency in film after film. But Oshima is no less an auteur, albeit in the contrary sense that - to paraphrase David Thomson's comment on Ichikawa Kon - variety is his most consistent trait. Thus his career has moved between jidai-geki (period drama) and gendai-geki (contemporary), live action and animation, the aesthetics of montage and those of the long take. Night and Fog in Japan experiments with the use of zip pans and sequence shots; indeed, there are said to be only 43 shots in the entire film. By contrast Violence at Noon, like a Soviet silent film, builds up a narrative from some 1500 separate shots, while Diary of a Shinjuku Thief (Shinjuku dorobo nikki, 1968) intersperses scenes of apparent improvisation with text inserts. The latter film, one of the Japanese cinema's most remarkable expositions of the spirit of 1968, is of all Oshima's films the most obviously influenced by Godard. Some have found this stylistic fluctuation opportunistic, but in truth the very different styles of successive works speak for Oshima's concern to explore the varied expressive potential of different elements of film form.

Yet to develop an understanding of the way in which Oshima's films break with, and at the same time build on, earlier cinema, it is instructive to examine one of his most classical films. Oshima made Boy in 1969, at the height of his critical acclaim (it ranked third in that year's critics' poll in the Japanese film magazine Kinema Junpo). Unlike many of his films, it tells a simple story in straightforward fashion: a boy is taught by his parents to fake car accidents in order to extort money from the ostensible culprits. More than many of his works, Boy is a film of direct and intense emotional impact: it is difficult not to be moved and outraged by its young protagonist's plight.

Yet Oshima's film can also be interpreted as a reinterpretation of and a riposte to Ozu. The composition of the family that Oshima depicts - father, mother and two boys - mimics the nuclear families of Ozu's Early Summer (Bakushu, 1951), Tokyo Story (Tokyo monogatari, 1953) and Good Morning (Ohayo, 1959), just as Oshima's interior compositions intermittently echo Ozu's. But the similarity points up the difference: in Boy, the woman is not in fact the biological mother of the elder boy, and the family is insecure and peripatetic, lacking a permanent home. In Ozu's Good Morning, a family dispute is occasioned by the children's demand that their parents acquire a television. In Boy, a scene in which the two boys sit glued to the television signals the family's achievement of something resembling normality: a normality achieved, ironically, only through crime, and doomed to be momentary and precarious.

Boy is also discreetly fixed in the context of Japan's recent history, in a way which again may be read as a response to Ozu. Ozu's later films may feature characters who have served in the war, or refer to characters who died in it, like the elderly couple's son in Tokyo Story. Ozu's treatment stresses the pathos of wartime suffering. The fact that the father in Oshima's film is himself a war veteran, whose arm was shattered in combat, is given more ironic political implications: he blames the wound for his inability to work. The war, Oshima implies, is the root of his criminality, and this story of the crimes of one particular family is thus offered to the viewer as a microcosm of the post-war Japanese experience, at variance with the official narrative of peace, reconstruction and economic growth. It is significant that this domestic tragedy unfolds under the flag of the rising sun which, as Audie Bock has observed, represented for Oshima “something dead: the Japanese nation since 1960”.

In one particularly striking sequence in Boy, the tensions within the family explode into violence, with the Japanese flag in the background. The quarrel, unlike most of the film, is shot in black and white, until the return to colour in the final shot of the sequence gives an extraordinary emphasis to the blood-red rising sun in the centre of the flag. Here, the effect is to increase the emotional intensity of the scene. Yet this is only one of several scenes in the film for which Oshima chooses to switch to black and white; often, the transition has the opposite effect - by disrupting the visual style of the film, it distances the viewer from the action.

In discussing Oshima's work, critics from Noel Burch to Maureen Cheryn Turim have evoked Brecht. Donald Richie has suggested that a more direct influence is that of expressionist theatre - before becoming a film-maker, Oshima belonged to a troupe that staged expressionist plays. But the comparison with Brecht is nevertheless instructive. Brecht coined the term Lehrstück, or 'lesson play', to describe his didactic approach: his characters learn nothing so that the audience may learn something. The celebrated Brechtian alienation effect was intended to ensure that the audience would not be absorbed into the fiction but, rather, would think objectively and critically about the events of the drama.

The richness of Oshima's work, however, lies in its ability to fuse alienation with involvement. His films balance realism and stylisation, just as his viewers are expected to respond both emotionally and intellectually. Thus Death by Hanging begins with a documentary depiction of the execution chamber and a detailed description in voiceover of the process of a hanging, before developing into a fantasy when the condemned man's body refuses to die. Nor does the film simply separate its realistic elements from its fantastic ones. The opening voiceover undermines the documentary qualities of the sequence by evoking the colour of objects and furnishings which, since the film is in black and white, the viewer cannot see. By contrast, the stylisation of the later scenes does not preclude an emotional response: the scenes where the prison officers re-enact the now amnesiac protagonist's upbringing and crime to remind him of his guilt are grimly hilarious.

It is this balance of involvement and distance which is the key to Oshima's art, not only in the films discussed in detail here, but also in the bold experimentation of Diary of a Shinjuku Thief and The Man Who Left His Will on Film (Tokyo senso sengo hiwa, 1970), and in the scalpel-like structural precision of The Ceremony (Gishiki, 1971). These are all films which repay detailed analysis - and which now, more than ever, challenge our viewing habits and our political assumptions. It's a final paradox that Oshima seems less contemporary than some of his elders precisely because his work was informed by a modernist aesthetic and by Marxist theory; ironically, it is these 'progressive' formal and political elements which now give his films a period flavour. Yet the concerns of his cinema - discrimination, inequality and the dangers of state power - are no less relevant in the 21st century than they were in the 1960s, and they pose crucial questions at a time when most of us in the developed world have chosen to retreat from political engagement, like the lovers in In the Realm of the Senses withdrawing into private concerns. In that sense, Oshima's work - never so unfashionable - has never seemed so vital or so probing.

An Oshima retrospective runs at BFI Southbank from 1 September. 'In the Realm of the Senses' is rereleased on 28 August