Primary navigation

Less interested in its heist than its characters’ psyches, Odds Against Tomorrow was a favourite of Jean-Pierre Melville – and Paul Tickell

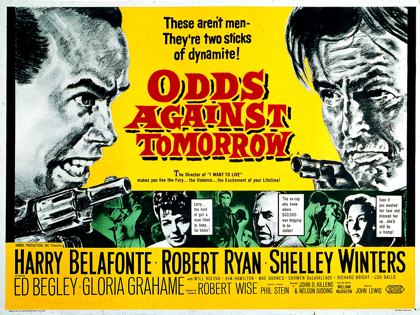

Although it gets the occasional screening and is available on DVD, Robert Wise’s Odds Against Tomorrow (1959) remains a neglected masterpiece. In its treatment of race and with its African-American star Harry Belafonte (who was also the film’s executive producer), the film is ahead of its time. It is also a testimony to Wise’s versatility – this is the director who gave us everything from The Curse of the Cat People (1944) to The Sound of Music (1965).

Odds Against Tomorrow is best described as a noir-ish heist movie. The heist movie often concerns itself with process – a minute but exciting examination of some spectacular robbery or kidnap. It also likes to linger over the fallout when the job goes wrong. But Odds Against Tomorrow shows little interest in the planning and mechanics of its heist – a bank robbery in a small industrial town outside New York. What really distinguishes the film is its concentration on what goes wrong beforehand – so much so that the robbery only occurs at the very end of the film.

The ending is truly apocalyptic, as the robbery leads to a shootout in a petrochemical plant and then an explosion reminiscent of Raoul Walsh’s White Heat (1949). But there’s no self-combusting Jimmy Cagney yelling, “Made it, Ma. Top of the world!” This is total obliteration – a damnation of biblical proportions without even the saving grace of Cagney’s gleeful nihilism.

The infernal flames are of a piece with the film’s opening shots, which depict New York as some kind of doomed, windswept city of the plain. The malign wind is more metaphysical than elemental, its force even greater in the first interior shots – of a hotel through whose lift shaft it howls like a banshee.

Things are already looking – and certainly sounding – bad. But Wise’s film is no parade of glib pessimism. It earns its despair. For screenwriter Abraham Polonsky (blacklisted as a communist during the McCarthy-era Hollywood witch hunts, and credited here as John O. Killens), tragedy is located in a set of social meanings, not some abstracted ‘human condition’. Polonsky’s interest in the social as well as the psychological – and ultimately also the political – is rooted in story and character. Most of what goes wrong before the heist, which is being organised by ex-cop David Burke (Ed Begley), can be attributed to the racism of one of his recruits – ex-con Earl Slater (Robert Ryan). Thus the bank robbery is doomed to failure for ‘personal’ reasons and not because of some breakdown in the plan or because of some great detective work.

Ryan’s racist – an interesting role for an actor so vociferous in real life on behalf of civil rights – is no cardboard cut-out. He doesn’t exactly gain our sympathy, but there is an understanding of his desperate circumstances. Stigmatised by his time in prison and out of work, Slater has a steady girlfriend, Lorry (Shelley Winters), but still feels like a loner. Further troubled depths are revealed when we see him first rejecting and then succumbing to the sexual advances of his neighbour Helen (Gloria Grahame).

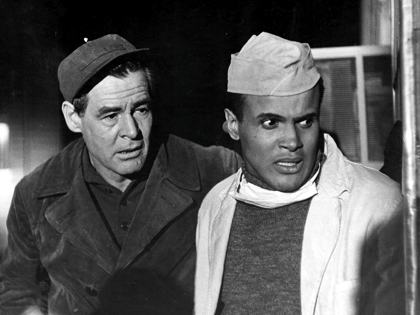

Just as Earl Slater is no straightforward villain, Ed’s other recruit, African-American Johnny Ingram (Harry Belafonte), is no obvious hero. (Slater, of course, hates him on sight.) Ingram is a nightclub singer who is certainly one for the wine, women and song – and the horses. His gambling debts leave him at the mercy of loan-shark gangsters. His womanising and general flakiness have led to a painful separation from his wife and their daughter. However, against the odds, he is trying to make a go of things. And failing.

The extensive location shooting in the film was pioneering, right from the windswept opening; the use of specialist infra-red stock makes the streets look utterly real yet somehow out of kilter, with Slater more like a ghost than a man of flesh and blood. This ‘estranged’ realism is carried over into scenes set in New York’s outlying districts, a phantasmagoria rather than suburbia: industrial wastelands and waterways jammed with flotsam and jetsam. Killing time before their bank job, the robbers feel equally washed up as they contemplate the floating jumble.

It’s in scenes like these that Wise gets behind his characters’ social personae and into their psyches. It’s all done by suggestion – by mood and image rather than crude psychologising. These are cinematic states of mind that have come to be associated with European auteurs, but here they are in 1950s America. Indeed Odds Against Tomorrow was French noir director Jean-Pierre Melville’s favourite film.

Wise, a former film editor who cut Citizen Kane, is adept at finding the fleeting moment that reveals a character’s soul. To describe such moments – for instance, when Johnny sees a discarded doll in the water – is almost to kill them by critique, like breaking down a delicate butterfly into its component parts. But it’s the parts coming together that produce these elusive moments. That floating doll conjures up the women in Johnny’s life, and that includes his daughter; but it’s also Johnny himself – with whom the gods are toying before they discard him. It’s all of these things and none of them. After all, Johnny is just looking and the film only suggesting. But that’s symbolism for you: the art of suggestion.

The score by John Lewis, pianist of the Modern Jazz Quartet, plays a big part in the making of such moments. It’s vibrant and aggressive, following events as they unfold while also at times leading them like some motivational force. But Lewis’s bebop hardness and objectivity (before the MJQ, he played with Charlie Parker) can also switch at the drop of a hi-hat into something more subjective and soul-searching.

These swift mood changes don’t happen without the light touch of editor Dede Allen, who would go on to work with Arthur Penn on Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Night Moves (1975). Gene Hackman’s private eye from Night Moves wouldn’t be out of place in Odds Against Tomorrow. Here’s a man who bites off more than he can chew, which is as good as asking the Fates to come and get you. And in Odds Against Tomorrow, they do. The genius of the film is that its Greek tragedy is rooted in the here and now of a racially divided 1950s America. And there’s no need for a chorus: the characters’ dry oneliners and gallows humour provide their own running commentary.

Paul Tickell is the director of the features Crush Proof and Christie Malry’s Own Double-Entry

“Strongly reminiscent of the sort of socially significant melodramas that Hollywood was making ten years ago. The same players are given the same melancholy-tough dialogue… and the message is still the same – a generalised plea for racial tolerance in a context of seediness and corruption… [it] emerges as an efficient but unnecessarily portentous thriller.”

— Monthly Film Bulletin, Feb 1960

“Robert Wise has drawn fine performances from his players. It is the most sustained acting Belafonte has done. Ryan makes the flesh crawl as the fanatical bigot. Begley turns in a superb study of a foolish, befuddled man.”

— Variety, 31 December 1958

Touch of Evil reviewed by Brad Stevens (December 2011)

Keep calm and watch films: Joshua Jelly-Schapiro sees the Harry Belafonte doc Sing Your Song at the trinidad + tobago film festival (October 2011)

Cerebral subversive: Peter Biskind pays tribute to the late Arthur Penn (October 2010)

Royal rapscallion: Andrew Collins on Gene Hackman (November 2005)

The big stealer: Nick James on Robert Mitchum (August 2005)

I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead reviewed by Ryan Gilbey (May 2004)