Primary navigation

For years Michael Shannon has been building a reputation as an intense, risk-taking actor on stage and in supporting roles. But his compelling turn as the dream-haunted everyman in Take Shelter proves he can carry a movie. Nick Pinkerton talks to him

Curtis LaForche, the protagonist of Take Shelter, is a husband and father living in rural Northern Ohio, the Midwestern state whose one-time tourist slogan, stressing its self-identified ‘middle-ness’, dubbed it “the heart of it all”. Curtis works for a gravel company, providing a decent home for his wife and young daughter, who happens to be deaf. There is hope that insurance will pay for an operation for the little girl; Curtis and his wife are setting aside any extra money for a summer beach house. They have a future.

There is a certain genre of contemporary country and western song that celebrates the simple joys of orthodox life in small-town America – call it the checklist song, the ‘got my truck and got my dog and everything is all right’ song. Curtis has ticked off just about everything he’s supposed to need: the pick-up and the dog and the ex-prom-queen perfect wife and the beer-drinking buddy who tells him, “You got a good life.”

But when he’s asleep, it all turns against him. In his dreams, the dog attacks him; his wife, holding a kitchen knife, glares at him with homicidal intent. The background of all of these night terrors is the vision of a storm building on the horizon, supernatural in its destructive power. As the self-conscious Curtis expresses it, when he’s finally able to express anything: “I’m afraid something might be coming. Something that’s not right.”

Curtis’s house sits in a wide, broad, bright expanse of flatland, but the dank, dungeon-like storm shelter in his yard, with its subterranean, enclosed space, begins to exercise an inexorable hold on him. (Here director Jeff Nichols finds a visual analogy to a troubled mind’s self-condemnation, and proves himself unusually skilled with the often arbitrarily used widescreen frame.) Curtis dips into the family savings, takes out a loan he can’t afford, violates his employer’s rules, undermines the tenuous security of his life – all so he can expand the shelter into something more like a civil-defence structure. As Curtis is doing this, he starts to think – along with everyone else around him – that he might be going crazy, like his mother before him. This question – whether Curtis is prophet or madman – forms the uncertainty on which Take Shelter teeters.

Take Shelter

Curtis is played by Michael Shannon, making his second film with director Nichols following 2007’s Shotgun Stories. The actor – whose slowly building reputation for intense screen performances culminated with a Best Supporting Actor nomination for 2008’s Revolutionary Road – spoke to me on the phone from a very different set in the Midwest. He’s in Illinois, shooting Zack Snyder’s Superman film Man of Steel, in which he’ll play the heavy, General Zod.

On a friendly sort of first-name intimacy with the characters he plays, Shannon explains the particulars of Curtis’s pathology: “If it was up to Curtis, none of this would be happening. He doesn’t relish it. There’s some people that may have some eccentricities or maladies but they kind of revel in them, or they’re not necessarily looking to get rid of them. And Curtis isn’t interested in being eccentric in any way. I think he’s ultimately ashamed of what’s happening to him – even more than afraid, he’s ashamed.”

Shannon has made a specialty of men coming undone. His lead performance in 2006’s Bug – the William Friedkin-directed film of the Tracy Letts stage play in which Shannon had also starred – established him before a growing audience as a screen actor capable of expressing rare shadings of disquiet. Bug in fact continued a project that had been underway since 1993, when Shannon – then barely 19 years old – first appeared in Letts’s trailer- park-gothic play Killer Joe, which opened in Evanston, Illinois and eventually took Shannon through the Edinburgh Festival to the West End’s Vaudeville Theatre.

“The formative experiences of my career really have been working on material written by [Tracy Letts],” says Shannon. “I guess my persona started crystallising during my work with Tracy, because before that I was really just kind of doing a hodgepodge of whatever could come my way. I started out in Chicago in very small theatres. It wasn’t until I started working with Tracy that I got a little more focused.”

Bug

Come 1997, Shannon’s focus was extending to starving himself to star in a production of Georg Büchner’s Woyzeck at London’s Gate Theatre – directed, at the actor’s behest, by the doomed Sarah Kane. Büchner’s play-fragment had famously been filmed in 1979, starring Klaus Kinski and directed by Werner Herzog, who in turn would direct Shannon in 2009’s My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done. None of this is coincidental. Like Kinski, Shannon is an actor who doesn’t let you see the gears turning – who doesn’t betray the process of decision-making in his fervid performances. When I point out certain mannerisms that recur in Shannon’s work, he discusses his ‘process’.

“You know, it’s something that’s really just impulse,” he insists. “I’ve thought maybe on certain occasions that it was something I should have more control over, but a lot of it is really just a matter of me not thinking too hard about what I’m trying to do as an actor and really just trying to get to the actual experience the person’s having. However my face looks or my voice sounds is a bonus if it’s good – but it’s not really in the forefront of my mind. I’m just really trying to have whatever experience that person’s having.”

Shannon’s pedigree, very much in the experimental theatre, is not generally a fast track to international recognition. But in 2006, the same year he directed Ionesco’s Hunger and Thirst in Chicago (“I knew if I didn’t direct it, then nobody else would, ’cause it was such a strange little play”), the film of Bug made an impact in Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes. (Its director, William Friedkin, seems to have returned to his early role as a bridge-builder between stage and screen: just as he filmed Pinter’s The Birthday Party in 1968 and Off-Broadway sensation The Boys in the Band in 1970, he recently completed a film of Letts’s Killer Joe with Emile Hirsch in the role originated on stage by Shannon.)

In Bug, Shannon’s character is harried by the idea that he has been stitched up with intrusive implants during US government tests. This delusion is strangely believable, as Shannon’s face is a minefield of tics; there is a squirming thing in him, and you can almost see something burrowing just underneath his skin, trying to break out. The imbalance of Shannon’s face is intrinsically suspenseful: is one eye slightly larger than the other? Whatever the case, Shannon’s off-centre close-ups are fraught with anxious anticipation; even in repose, his face has the quality of an object poised on a ledge, ready to tilt and drop at any second.

The Runaways

Shannon is equally effective in wide shot. He is a big man – six foot four and solidly built – and part of what makes Curtis’s plight so affecting in Take Shelter is the sight of this strong, seemingly self-reliant fellow reduced by suffering – even wetting the bed at one point. His size also gives his vulnerability an undertone of potential threat, which in Take Shelter manifests itself in one cloudburst monologue after a whole film of leaden skies. (“There is a storm coming!” he bellows.)

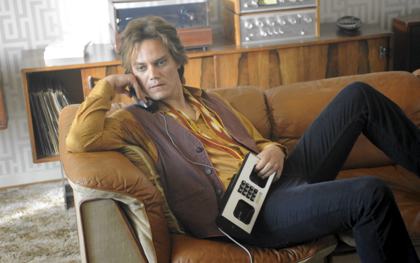

Shannon can fling his big frame about with abandon; in fact one of the delights of The Runaways (2010) is watching Shannon, playing would-be Svengali and bounding glam-Frankenstein Kim Fowley, nearly scraping his head on the low ceilings of his band’s rehearsal trailer. Playing producer/hustler Felix Artifex in the 2010 Off-Broadway production of Craig Wright’s Mistakes Were Made, Shannon was a dynamo, pleading with and placating moneymen and talent through juggled multi-line calls, spewing saliva the length of the stage, tethered to his desk by his phone cord – the anchor that keeps him from launching into the stratosphere.

Curtis’s fear in Take Shelter is a flexible metaphor, one that resonates in a time when – don’t you feel it? – the world seems to be built on sand. The film taps the free-floating economic incertitude particularly felt among the working class (“You take your eye off the ball one minute in this economy, you’re screwed,” says Curtis’s older brother during a common-sense talking-to) and the fear of apocalyptic natural disasters so much in the news.

Take Shelter’s characters are never mere metaphorical placeholders, however, thanks to Nichols’s firm grounding in the particulars of his setting, both physical and social – the commmunal fish fries and enforced family dinners – and the undressy, lived-in supporting performances from Shannon’s Boardwalk Empire co-star Shea Whigham as Curtis’s workmate and friend Dewart, and from the now-ubiquitous Jessica Chastain, doing quiet, alert work as Curtis’s wife Samantha. Even the nature of Curtis’s bad dreams is grounded in a very real regional specificity: I have a friend who grew up not far from the setting of Take Shelter, in the tornado-prone stretch once called the Great Black Swamp, who is still disturbed today by something she calls the “Terrible Tornado nightmare”.

Take Shelter

Take Shelter also plugs into more quotidian fears. As Shannon puts it: “I feel like a lot of the film is kind of a poetic expression of some actually fairly common anxieties I think most men deal with at some point in their lives, making that transition from being a young, carefree man to being a family man.” Here Shannon found his own point of entry into the material. “There was a lot of synchronicity for me doing this role, in that I was having some similar experiences to Curtis’s – not with the dreams or hallucinations or anything, but just starting a family. I was wondering if I was good enough to be a parent. In the film, Curtis’s father had passed away recently, and my father had passed away recently. In the film it’s a pretty subtle detail, and I don’t talk about it a great deal, but I think it influences what Curtis is going through, and maybe inspires some of the dread and anxiety he’s dealing with.”

Before relocating to live with his father in Chicago, Shannon grew up in Lexington, Kentucky, where he found a real-life model for taciturn Curtis. “I used to have a stepfather named Big Mike,” he says. “He was Big Mike and I was Little Mike. My mother married him after she had been with my father. And she and Big Mike had three kids together, so we all lived together for a little while. He is definitely a prototypical example of one of these guys who can’t really say very much about what’s happening inside of them, what’s happening in the world in general. They just kind of get up and go to work, come home and eat dinner, they like to throw the ball around in the backyard – and that’s about it.”

Considered mad for prophesying coming catastrophe, Curtis can’t but remind a viewer of another patriarch: Noah. I point out a biblical through-line in Shannon’s roles – his character in Shotgun Stories, known simply as “Son”; the King James phrasing of My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done; the ‘vengeance is mine’ role of Agent Nelson Van Alden in the HBO series Boardwalk Empire. “He really is Old Testament,” says Shannon of Van Alden. “He’s coming from a real fundamentalist background. I think he probably grew up in a cabin with a mud floor and no presents at Christmas.”

Take Shelter

When asked for career models, though, Shannon gives a slightly unexpected answer: “Oddly enough, I find Jimmy Stewart to be very inspirational. Talk about a career that had range! He really did so many things: to be Capra’s go-to guy and Hitchcock’s go-to guy and the western’s go-to guy…”

I mention another actor he reminds me of, Robert Ryan. Like Shannon, Ryan had the same stooped, effaced tallness, and evokes the same combination of menace and pity. Look at Ryan, for example, as the drifter who menaces Ida Lupino in 1952’s Beware, My Lovely – a performance that splits a viewer’s concern between fear for Lupino’s safety and empathy for Ryan’s lacerating anguish. With Shannon, as with Ryan, one has a sense that filmmakers and casting directors consider him a potential threat to women, thus barring him from the higher plateau of stardom that comes with romantic leads.

“You know I actually got real close to landing a job like that recently,” Shannon tells me. “I had gotten all the way to the point where I was reading with the leading lady – it was the last inch to the finish line – and I think the director just realised there was something about it. As big a fan as he was of my work, there was something about it that wasn’t quite jiving.”

With Shannon, as with Ryan, there is an unsettling, radiating darkness that seems to come from somewhere beyond what can be taught. And that’s something at least as valuable as range – the very rarest thing, in fact, in American pictures.

‘Take Shelter’ is released on 25 November, and is reviewed in the December 2011 issue of Sight & Sound

Odds Against Tomorrow remembered by Paul Tickell (December 2011)

A Serious Man reviewed by Michael Atkinson (December 2009)

Out of the rubble: B. Ruby Rich on World Trade Center (October 2006)

The Perfect Storm reviewed by Andrew O’Hehir (September 2000)

The Iron Giant reviewed by Leslie Felperin (January 2000)