Primary navigation

Evoking his family’s life in their Pyrenean hideaway, This Our Still Life is a mesmerising blend of lyrical intensity and freewheeling impressions from unclassifiable British filmmaker Andrew Kötting. By Iain Sinclair

The magic and mystery of the hyperkinetic Andrew Kötting’s drama lie in the sweet torture of the constant striving for a stillness and silence he cannot endure, but which he is obliged to overwhelm and decorate with manic voices, archive, insects, steady infusions of light and love. There is no one quite like him in cinema.

And that’s just as well, because the energy displacement of this lurching between documentation, performance, mangled quotation, leaves the audience on the ropes, emotionally shredded, eyeballs branded with shimmering images and merciless sounds. All the eidolons of a very solid transience are presented for our delight, but grasp at them and they’re gone. Back into the paintings on the cabin wall, into an elective Walden Pond, into Mr and Mrs Kötting portrayed as a parody of Grant Wood’s American Gothic.

Gallivant (1996) – a camper-van tour of the whole island of Britain, a three-month endurance test during which Kötting explored and celebrated his bond with a feisty grandmother and a bird-voiced daughter, Eden – captured me completely. And I have followed him, wherever he wanted to go, from that day on.

He has tracked the ghost of a difficult father, and all those associated and troubling memories, across the globe, for his installation/book project In the Wake of a Deadad: from South London suburbia to the Faroes, to Hollywood and Mexico. With his obliging brothers, he swam the English Channel.

He makes art as he breathes, hard and fast: things in boxes, revised maps, paintings, postcards, installations, rants, poems, freewheeling film ‘songs’ in the tradition of Stan Brakhage – and collided and collapsed feature narratives, peopled with fabulous gargoyles and tree-climbing acrobats. When he can, he collaborates with Eden. He has invigilated her from the start, touching her tongue to stimulate speech and to counter the ‘lolling’ effect of Joubert’s syndrome, which defines, but never circumscribes, her existence.

This Our Still Life is established, securely, at a mountain retreat in the Pyrenees, a whitewashed trackside house with blue shutters and windows on the enveloping forest. Here, between 1989 and 2010, on a Samsung Digimax L85 and a Nizo super-8 camera, Kötting recorded the active diary fragments, the snapshot meditations and topographic sweeps that he has stitched together as a tribute to place.

Perhaps ‘retreat’ is not the best term for the ruined and recovered building, which appears to be an abandoned auberge on a pilgrims’ route through the mountains, between France and Spain, somewhere that would sit comfortably in Buñuel’s The Milky Way, or witness contraband carriers, spectres like Walter Benjamin trying to escape from a Nazi-occupied country.

Kötting’s exile is self-willed, a break from the furious pace of production that holds a certain temperamental melancholy at bay. But stillness is not possible. The camera roams in neurotic interrogation to animate the frame, tracking shafts of sunlight through smoke, bees on buddleia, rotting rodents, slithering snakes, toads on the hand, lizards on the wall. As a testimony built from affection, from intimacy with place and its accumulated objects, a home movie in the purest sense, this is a return to the earliest and most domesticated form of cinema. These are the brave accidents we hope to secure against our inevitable mortality.

The film opens on a time-lapse humming with decay, the rotting of a small native animal. Insect babble sets the speed dial for language too swift for easy interpretation. Awkward human intervention in this magnificent sweep of rocky landscape is absurd and doomed to failure, even when it yields such delicious comedy.

Only Kötting could collide Brakhage’s lyrical intensity, that probing at the edge of focus, with the stutter and stammer of Benny Hill’s caricatured Englishness. The funny voices. The portentous and culturally freighted subtitles. Upper-case announcements of the passing seasons, like a parody of Disney or David Attenborough, fix the mood for the next convulsive movement. We are offered a desert-island survey of all the found objects in Kötting’s mountain ark, the sacred and the surreal. Edible colours and images so ripe you can sniff the perfume of water beads on drooping leaf.

These people present themselves as the first human family and the last. A small Swiss Family Robinson commune who play very seriously at wilderness before returning to wherever they came from, before they bumped along this mountain track in wobbly, early archive footage – when Eden was a babe and her mother smiled and ducked away from the camera, or was caught, as in primitive diary form, bathing in a tub.

The whole process is wrapped in compulsive synaesthesia, painterly spills and splashes rendered as blots of sound: straw-hat Elvis karaoke or moody sonic conjurings by the ever-attentive Scanner. “The local,” the critic Gareth Evans wrote, in response to this film, “in both heat and hearth needs to be radically re-imagined as the prime locus of our needs and search for belonging.”

Kötting’s local is an inch from his skin, a fat white snail held out to test his daughter. He peeps and probes from behind wild flower meadows and outcrops of rock. The house itself, its diurnal rituals recorded, sketched, scribbled over, becomes a screen for a projected spectacle. It is cinema as architecture. The lit windows are a play of shadows and movement, as the filmmaker/voyeur retreats into the forest.

Kötting has spoken about being in this place, at Louyre, alone, and needing to step back, to stay in the darkness. The empty house is filled with ghosts. In coming outside, he confirms the status of the recovered dwelling as a theatre of absence. This Our Still Life, in all its zany slapstick activity, contrives an argument between stasis, objects laid out on a table to be described and recorded, and the enormous space and presence of the rocks, the forest, the night.

This is not, finally, the still life of the family group who are playing, with proper respect and attention, at wilderness. This is their memory-mash, their summer songs, their winter walks to old Albigensian stronghold-ruins. There is the steady recording eye of the poet, work that parallels Gary Snyder’s reports from Mount St Helens in his collection Danger on Peaks (2004). “Step by step, breath by breath – no rush, no pain.”

So you have the solitary, the man with the camera-notebook, and you have the supporting family group. And you have the house, a temporary shelter, a block of soft-lit windows, of other lives remembered. And you have the grey ridges, the caves, the snow peaks. There was one extraordinary moment when Kötting came back, after one of his nocturnal expeditions into the dream of the forest, to hear the voices of his wife and daughter, who were already safely returned to England. One of his recordings had activated itself. Electronic retrievals played, spontaneously, against the accumulated layers of mountain silence.

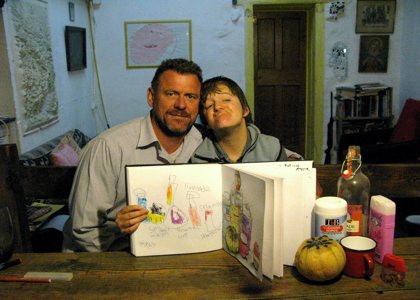

As Brakhage had it, “First we must deal with the Light of Nature, then with the Nature of Light. And set your science aside, please, as we’ve no more use for it than what is of it as embodied in the camera in hand.” The doubling of eye / mind exposure and capture is the germ of this project: father ‘directing’ daughter as she sings or paints. Father and daughter learning, one from the other, as they make an inventory of objects, relics and household devices.

This is naked cinema, a thing of great value in a period of cultural stagnation and economic adventurism. This is the analogue presentation of the shadow on the cave wall teased into the digital age. And yet another file in the exuberant and ever-expanding Kötting catalogue, the multivoiced self-portrait of an artist without artifice, an art-worker learning to live in his own still life.

Andrew Kötting talks about the inspirations behind This Our Still Life in the December issue of Sight & Sound

This is our land: Frances Morgan on liminal Britain at the London Short Film Festival (January 2011)

Ivul reviewed by Nick Bradshaw (August 2010)

Play away: our Young Journalism Competition winner Jamie Chadd interviews Andrew Kötting about Ivul (November 2009)

This Filthy Earth reviewed by Peter Matthews (December 2001)

The cruel seaside: Iain Sinclair on Last Resort (March 2001)