Before The Rain

The venerated Japanese director Akira Kurosawa is best known for his period Samurai epics, but his rich career also took in sharp urban dramas. Philip Kemp looks at three of the best.

Among his collaborators and crew, Akira Kurosawa was known as kaze-otoko - 'wind man'. (The nickname tenno - 'emperor' - was wished on him by the Japanese press.) It's not hard to see why. From the scuttering of windblown leaves that provides a dry, mocking ostinato to the dances of death in Yojimbo (1961) to the pennants snapping and fiuttering above the doomed armies of Ran (1985), his characters are buffeted by winds of fate. But it's not only wind. Throughout his work, weather plays such a determining role it almost becomes a character in its own right. In Dersu Uzala (1975) the chief adversary is no human agency, but the vicious Siberian cold that all but kills the inexperienced Russian surveyor; the mists that drift around Cobweb Castle in Throne of Blood (1957) seem emanations of the otherworldly forces that lure Lord Washizu (the film's Macbeth figure) to his downfall. And no Kurosawa movie feels complete without at least one torrential downpour - most unforgettably in the 25-minute battle that climaxes Seven Samurai (1954), with the swordsmen skidding and sliding in the mud and slashing wildly at the bandits as they canter by.

Interestingly, the one climatic extreme largely absent from Kurosawa's period films is intense heat. It's as though for him the world of the jidai-geki (period drama) operates at a cooler, more remote level. Heat he reserves for his present-day urban stories, presenting it as correlation of the social meltdown of post-1945 Japanese society, with endemic crime and corruption replacing feudal oppression as the country's besetting disorder.

In three Kurosawa movies in particular, the scope and slant of the action are not just coloured, but virtually defined by an oppressive heatwave. The crime dramas Stray Dog (1949) and High and Low (1963), and the psychological drama I Live in Fear (aka Record of a Living Being, 1955), are all pervaded by images of relentless, inescapable heat. Every character, male and female alike, is constantly dripping with sweat. Shirts stick wetly to backs, foreheads are mopped, hats and newspapers waved in futile quest of a breeze. Outside the sun beats pitilessly down on pedestrians inching along dusty, airless streets, hugging the walls to catch the least sliver of shade. Interior scenes are nagged by the whine of electric fans, whose ineffectual clamour seems only to fray everyone's tempers further.

It's as if the heat in these films was not so much the cause as the end result of human aggression, a form of emotional global warming. Anger is the element in which almost everybody swims, with most of the characters operating somewhere along the scale from irascibility to outright fury. In this short-fused atmosphere, violence is the inevitable outcome, with the killer in the two crime movies an erupting boil on the unhealthy skin of society - worse than others in degree, perhaps, but not in kind. In both films the pursuing detective comes to feel a perverse identity with his quarry, seeing him as the man he might all too easily have become.

But Kurosawa takes his heat imagery a stage further. In all three of these films a character makes a descent into hell. In the two crime movies he manages to survive and return; in I Live in Fear the protagonist descends into a mental hell of his own making and ends up trapped there forever, gazing at a nightmare vision of the world on fire.

The Orpheus figure in Stray Dog is a young police detective Murakami (Toshiro Mifune) who has his gun stolen by a pickpocket. Humiliated by the loss and taking it as a personal slight, he sets out to hunt down the thief - a quest that gains in urgency when the stolen gun becomes a murder weapon. Tipped off by a prostitute that the gun may be sold on the black market, Murakami takes on the guise of an unemployed drifter and, in a virtuoso eight-minute dialogue-free montage sequence, roams through the sleazy underbelly of Tokyo, his casually slouching posture at odds with the fierce watchfulness of his eyes. Though Stray Dog was one of Kurosawa's biggest successes prior to Rashomon (1950), he always spoke of it disparagingly - 'It's just too technical. All that technique and not one real thought in it' - and this montage sequence may suggest why. Powerful and visually inventive though it is, with a sense of documentary authenticity and backed by Fumio Hayasaka's atmospheric score with its snatches of nightclub jazz, it looks a little like bravura technique for its own sake. Half as long would have been just as effective.

Stray Dog, like so many of Kurosawa's early films, teams his two favourite actors, Mifune and Takashi Shimura, pivoting the action around their contrasting and complementary screen personas. Shimura plays Murakami's section chief Sato, calmer and more settled in his personal life and a steadying infiuence on his younger colleague. This seems a touch schematic, and we might also expect him to be the more tolerant of the two, with greater sympathy for human weakness. But Kurosawa shows us the downside of the older man's apparent good nature: to him, all the criminals he pursues are simply evil, to be eliminated. Murakami, for all his anger and personal resentment against his quarry, can't see it so simplistically. 'I can't think that way yet,' he says. 'In the war I saw men turn bad very easily.' (The war, still recent, casts a long shadow over the film. 'He changed completely after the war,' says the killer's mother, smiling helplessly.) Murakami's 'yet' is pointed. Give him time, and he may well become like his boss - outwardly more amiable, but with the crucial sensitive edge of his human sympathy eroded.

For the moment, though, as Sato notes, his young colleague has a lot in common with the man he's hunting. 'You understand him too well,' he warns, quoting a saying that 'Mad dogs only see what they're after.' Murakami, with his obsessive pursuit, is turning into a mad dog himself, slavering and panting in the heat. Eventually even Sato starts to share in the single-minded obsession; heat is a great leveller. But the pursuit gets nowhere until the weather breaks, the skies opening in one of those torrential Kurosawan drenchings. Yet though the case is solved, there's no easy closure to grant us release. When Murakami finally confronts and disarms him, the killer - who's no more than a youth - doesn't snarl defiance but howls abjectly like a punished child. We're left with a desolate sense of lives distorted and wasted.

High and Low, made 14 years later, shows us a Japan growing prosperous and - it seems - healed from the wartime wounds. Some have even done well enough to be able to ignore the sweatbath of summer, living high above the urban sprawl of Yokohama in air-conditioned villas, well placed to catch any breezes that blow. One of these privileged individuals is Kingo Gondo (Mifune), a rich industrialist scheming to seize control of the ill-managed company he works for. At the crucial moment an attempt is made to kidnap his son. It's bungled; the kidnappers mistakenly seize the boy's playmate, son of Gondo's chauffeur. But they still demand the same vast ransom, reckoning Gondo's conscience will work in their favour. If he pays up his plans will collapse and his career will be ruined.

This dilemma, though, proves not to be what the film is about; it's even something of a macguffin. Or perhaps a semi-guffin, since it preoccupies the first half of the movie. High and Low makes the metaphor of a descent into hell even more explicit; in fact, the film's Japanese title, Tengoku to Jigoku, literally means 'heaven and hell', and the action splits between these two locations. The first half of the film plays out in 'Heaven', Gondo's luxurious villa, as he wrestles with his conscience, consults the police and finally decides to pay the money demanded. This section of the film is shot soberly; Kurosawa, foregoing his usual dynamic editing style and oblique angles, films in long, unbroken, meandering takes, giving precedence to the dialogue. We might almost be watching a filmed play.

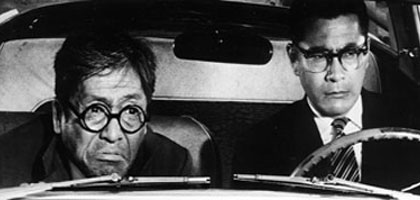

Once the ransom's paid and his career is ruined, Gondo virtually drops out of the action. The actual handover of the cash, a virtuoso four-minute sequence shot aboard a high-speed train in real time, acts as a midway interlude after which we descend into hell, following the police investigation through the grimy inferno of midsummer Yokohama. This soon becomes a murder hunt, since the kidnapper kills his accomplices to cover his tracks. In this half of the film Kurosawa reverts to the style of film-making we expect at this mid-stage of his career - restless, dynamic, fuelled by nervous tension, with a fast mobile camera, insistent cutting and swift horizontal wipes that speed the action and mirror the urgency of the police investigation. Led by Inspector Tokuro (Tatsuya Nakadai, Mifune's chief opponent in Yojimbo and later the star of Kagemusha, 1981, and Ran), the cops penetrate steadily down into the murky depths of society, to the sordid waterfront bars and heroin dens where the killer hunts for fresh victims, a far cry from Gondo's elegant villa.

But we're constantly reminded of that villa, perched high above the city in aloof seclusion. Every so often Kurosawa's camera lifts from whatever grimy back alley the police are raking through, and there it sits, cool and white and far beyond the reach of the sweltering masses below. It's precisely that contrast, in fact, that first impelled the kidnapper, an impoverished young intern, towards his crime - as he tells Gondo when they at last come face to face. 'Your house looked like heaven', he says accusingly. 'Hate made my life worth living.'

Here, as in Stray Dog, the cops find they're starting to align themselves with the criminal, to share his viewpoint. 'That house makes you angry,' growls one of them, dusty and sweating, gesturing at Gondo's villa, 'as if it's looking down on you.' Once more it's a moot point whether the soaring temperatures are the cause or the outcome of so much festering social resentment.

Made midway between Stray Dog and High and Low, I Live in Fear is one of Kurosawa's strangest and most personal films, and here too the all-pervasive heat seems as much a mental state as a physical condition. Again the protagonist is an industrialist played by Mifune, but his character could hardly be more different from the urbane, calculating Gondo. For a start, Kiichi is a 70-year-old patriarch; at the time he made the film, Mifune was exactly half that age. It's an extraordinary performance, undertaken with utter disregard for naturalism, let alone credibility. Eyes glaring from dark facial make-up (as though his skin has already been seared by the nuclear blast he so fears), scowling ferociously, clenching his jaw and jutting out his head like a tortoise, he never for one moment convinces as a septuagenarian. Instead he gives us a fierce expressionistic sketch of a man still bursting with youthful willpower and mental energy, furious at finding himself trapped in an ageing body.

Once again images of heat and anger set the mood. Right from the start Kiichi is simmering with ill-suppressed rage, brandishing and snapping his hand-held fan as though he'd like to hit someone with it. This mood, exacerbated as ever by the pitiless heat, transmits itself to those around him, and the family conferences that punctuate the action mostly degenerate into shouting and violence. The family business is a foundry, a place of heat and raised voices, which eventually burns down - one might almost think, from spontaneous combustion. But in fact the fire is Kiichi's doing, part of his monomaniacal plan to force his whole family - including his mistress - to leave Japan and move to Brazil, where he thinks they'll be safe from the nuclear confiict about to engulf his country.

The fear of nuclear holocaust was far from unreasonable in 1955, with the Cold War at its height and the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki a raw, recent memory. As Dr Harada (Takashi Shimura), a volunteer in the Family Court where Kiichi's family battles things out, remarks, 'It's a feeling that all us Japanese know only too well.' The previous year, 1954, H-bomb paranoia had given birth to the first of the Godzilla movies, sublimating public anxiety into the image of a cartoon monster created by irresponsible nuclear testing. Kiichi - like the killers in Stray Dog and High and Low - is different not in kind but in degree from those around him. Stubborn and reactionary, he takes his fear beyond the bounds of sanity and arrogates to himself the right to make decisions for his whole family.

For I Live in Fear isn't finally about the fear of nuclear weapons. Kurosawa uses this theme as a way of exposing the damage caused to Japanese society by its long tradition of patriarchal despotism. Kiichi is a bully, demanding unquestioning obedience from his family and outraged when it's withheld. Only when he realises that in his obsession he's caused the ruin of his loyal workforce does he feel shame, and the shock unhinges his mind. He ends up confined to a mental hospital, believing that he's moved to another planet safe from nuclear war. 'What's happened to the Earth? Still many people there?' he asks Dr Harada, who's come to visit him - and then, glimpsing the setting sun, 'Oh my God. It's burning. The Earth is burning. Burning.' The heatwave has broken and the rains have come, bringing relief; but Kiichi, trapped in the hell of his own mind, will never know it.

The Kurosawa season at London's NFT runs through January and February. The director is familiarly known in the west as Akira Kurosawa, so Japanese names in this article appear in the western formulation, with surname second.