Primary navigation

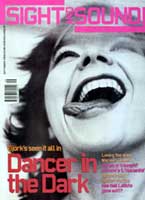

Lars von Trier's anti-musical Dancer in the Dark sparked protests when it won the Palme d'Or this year, but José Arroyo thinks it's as exhilarating as it is exasperating

Watching Dancer in the Dark I kept wondering whether director Lars von Trier wasn't experimenting his film right down the toilet. Here Denmark's ageing enfant terrible mixes genres, bucks conventions and eschews celluloid; his direction is formally innovative and visually daring. The performances, particularly Björk's, are riveting. But is this film that begins with a song from The Sound of Music, 'My Favourite Things', and ends with its heroine hanged from the gallows a challenge or a cheat? Does it all add up? For once reports of booing and hissing at Cannes can be believed. Yet the wildly differing receptions this film received there were probably not between individuals but within them: Dancer is as exasperating as it is extraordinary.

It tells a simple, melodramatic story: Selma (Björk) works day and night to afford the operation that will save her son Gene (Vladica Kostic) from the blindness he will genetically inherit from her. Bill (David Morse), a cop neighbour, attempts to steal her money and forces her to kill him. It looks like murder: her goodness makes her a victim. That there is no last-minute reprieve is not the most unusual thing about this story. To begin with, it's told as a musical.

Making Dancer in the Dark a musical melodrama is an odd choice and an inspired one. Musicals and melodramas both deal with expression and emotion, but in very different ways. In musicals, characters leap into dance or break into song when they're bursting with a feeling they can't contain; in melodrama, the protagonists also feel intensely but they have to repress its expression - only the audience is witness to the burdens of their knowledge. Where the terrain of musicals is romantic love and the formation of community, the terrain of melodrama is generally that of the family, romance and the psychosexual havoc which results from trying to live up to socially imposed sexual mores. At their best, say Meet Me in St Louis (1944) or Written on the Wind (1956), musicals and melodramas are lush, stylish, excessive - they accentuate or reveal emotional states through mise-en-scène

Using a melodramatic situation as a structure for a musical offers von Trier a basis from which to work against the musical's conventions. First of all, it is rare that characters in musicals have any kind of job except in show business. Here Selma is a factory worker, seen working at a steel press. Moreover, in the rare musical where factory work is involved, such as The Pajama Game (1957), the musical numbers are an indication of a sharing in community. Here Selma has to withdraw from the community into her own head before the music starts.

In combining the conventions of musicals and melodramas while simultaneously working against them, von Trier has achieved a rare feat: Dancer is a musical about alienation. Selma is loved by her best friend Kathy (Catherine Deneuve) and her admirer Jeff (Peter Stormare). Even the cop Bill admires and, one suspects, loves her, not the least for her goodness. But it is this very goodness, combined with a single-minded certainty, that cuts her off from them and from the world. Selma's love for her son Gene is overwhelming, overriding every other human relationship. She can't allow herself any other emotional attachments, and can't even allow her son to feel loved because he needs to be tough to face the future that awaits him. Selma's estrangement has a purpose, but her resulting isolation is no less intensely felt.

If Selma's love for her son cuts her off from the world, it's her love of music that makes her feel alive. In her interior dream world, abstract noises become concrete as music. A good example of this is the 'Cvalda' number early in the film. Selma is at the factory. The noise of the machines is the traditional cue that a number is about to begin. Industrial noises create a rhythm that is then enveloped, developed and swept up by a full orchestra on the soundtrack. Selma sings, "Clang the machine, what a magical sound, so clang the machines, they greet you and say, we tap out a rhythm and sweep you away." Her co-workers join in the dancing as Selma sings, but at the end of the number, when Kathy wakes her from her dream world, she finds herself alone. Moreover, her lack of attention to her work has meant she has almost broken the machinery. The number is not about the celebration of work, as in the Eastern Bloc musicals the film refers to; it's about how work is such a drudge that even industrial sounds provide an escape. The escape into herself is depicted as a joy, yet a dangerous one because it puts what is already a threadbare living in danger.

Aspects of Dancer in the Dark are so recklessly ambitious they're thrilling. Is it conceivable for musicals to be gothic? Well, Dancer has a musical number with a corpse. After shooting Bill, Selma breaks into a musical dialogue with his ghost where explanations are given and forgiveness is granted. Selma even sings to Bill's wife, gently judging and blaming her for being criminally unconscious of what is happening around her. This kind of song dialogue risks risibility. It's what the Marx Brothers used Margaret Dumont to caricature in their films - the fat lady at the opera who has to struggle through several octaves merely to trill 'open the door'. But as lovers of opera know, these musical dialogues, properly judged, are the grounds for differentials of knowledge among characters that create a moral dimension to the work and allow it the scope of tragedy which is closed to traditional operetta and musical comedy. Here Selma and Bill know the reason for the killing. The fact that Bill's wife, representing the rest of society, is ignorant and misunderstands everything, is what enables the film to take on a tragic dimension. The highly stylised, quasi-gothic form of this number is balanced by the effect of emotional realism that Björk and her music succeed in conveying.

The most beautiful number in the film is 'I've Seen It All'. It takes place shortly before Selma kills Bill. Selma is walking home along the railroad having been fired from her job. Her admirer Jeff, who is following her, realises that she is going blind when she is nearly hit by an oncoming train. Just as with Judy Garland in The Harvey Girls, the sounds of the train's wheels on the track are the cue for a song. As Selma starts to imagine herself inside a musical number, the cinematography seems to be filtered by amber tones, and moments appear in slow motion. While Selma removes her glasses and prances, the song she is joyfully singing indicates a generous resignation to a life already lived: "I've seen what I was and I've seen what I'll be, I've seen it all there is no more to see." While the duet is being played out, the men on the train dressed in western gear mournfully perform some slow movements: they may look like the exuberant frontier men in Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, but their actions are gracefully restrained, almost muted. The number is the emotional core of the film, but also indicates why the film doesn't work as a musical: there are problems with the music, the dancing, the tone.

Dancer in the Dark underlines its intertextuality and cues the audience to its uniqueness by generic references that are meant to situate it within and distinguish it from the musical. At the beginning of the film we are told how unrealistic it is when characters burst into song in musicals. Selma talks about how in the last number in a musical, a sweeping crane shot always makes the camera seem to go up through the roof; she says she always tries to miss this bit because it's a sign that the film is about to end and she prefers to think the singing and dancing go on forever. Later on, when she's walking to the gallows, she sings about how there's always someone to catch her when she falls, because this is a musical. But of course there isn't. It isn't that type of musical.

But what type of musical is it? The film refers to Busby Berkeley by citing his famous geometric overhead shots. There are also plenty of references to the MGM musicals directed by Vincente Minnelli, Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly. The presence in the film of Deneuve and Joel Grey instantly brings to mind Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (1964) and Cabaret (1972). Grey's character, the Czech tap dancer Oldrich Novy, carries an awareness of musicals from what used to be called 'Iron Curtain' countries. And of course, The Sound of Music, which Selma is rehearsing with the local amateur dramatic group, refers to the famous 'integrated' musicals from Broadway which Rodgers and Hammerstein are credited with inventing with Oklahoma! (1955). But Dancer is not quite like any of these models, for though it shows an extraordinary awareness of the genre, it doesn't show much sensitivity to an audience's pleasure in it.

One of the reasons why Dancer is exasperating is that music, dancing and mise-en-scène are all problematic, albeit in different ways. The problem is not necessarily the music per se. Björk has composed an extraordinary score, melodic and complex, which contributes to and develops the film's narrative. Hearing it on CD, my admiration increases with each listen. But watching the film, one only hears it once, and on first listen it sounds samey. Possibly this is because Björk is the only singer in the film, and has a very particular and distinctive style. As the film unfolds, the songs become hard to distinguish from each other. One does not whistle a happy tune coming out of this film.

Dancer is also insensitive to dance. Von Trier has bragged about how he used 100 cameras to film the musical numbers as it freed him and the performers and offered surprise moments that wouldn't have been captured if the numbers had been carefully storyboarded. However, this also meant it was impossible to co-ordinate dancers and camera and thus construct a true filmed choreography. There are snatches of the numbers in the factory and the railway that suggest that Vincent Paterson's choreography might have been marvellous. But who's to know? The way the numbers are filmed and edited privileges 'surprise moments', so what we get is a series of occasionally interesting movements rather than the poetic communication of mood, tone and intensity of feeling we expect of filmed dance.

The film's look also contributes to its status as an 'anti-musical'. First of all, it's drab: Selma wears ugly, worn print dresses; her house is so bare, a tin chocolate box becomes a symbol of richness; the non-musical sequences are shot in dreary browns and metallic greys. Second, the film is shot on digital video, which makes the image feel thin and somehow incomplete. Traditionally musicals and melodramas convey a feeling of richness, which derives partly from costume, colour and camera movement, but partly from the use of celluloid itself.

Celluloid gives a rich, textured image with a depth of tonalities and a range of sensitivity to light. In 35mm even scarcity comes across as plenitude, and it seems perverse to film a story dealing with extreme states of feeling in thin digital video. But of course, frustrating as they are, all of these elements add up to a carefully chosen aesthetic. It's frustrating in terms of expectations of the traditional pleasures of the musical or the melodrama, but the various elements cohere as an organic attempt at a stylised kind of realism. The film becomes thrilling in the moments when one is aware that these odd, usually impossible, choices actually work.

Many elements in Dancer in the Dark initially come across as profoundly irritating, but as the film progresses their raison d'être as aesthetic choices becomes clear. As in von Trier's earlier Breaking the Waves (1996), the film is mostly shot with handheld camera and plays with the traditional rules of continuity editing. Rather than cutting to a reverse shot in a conversation, for example, von Trier does a swish pan (the equivalent in literature of constantly repeating 'he said' or 'she said' after every line rather than merely using quotation marks). However, as the film continues to anchor itself in characters' faces, it becomes clear that the swish pan, a non-cut, also has a narrative value. The device creates an urgent expectation of a response. Likewise filming on digital video initially feels like a cheat. Then one realises that this thin look fits in with the grimness of Selma's life. Moreover, cinematographer Robby Müller creates a look for the musical numbers that is similar to old 8mm Technicolor footage. The cinematography thus creates a sense of 'pastness', an evocation of memories in danger of fading. The film is set in the 1960s in an imaginary America, and its look underlines that the past is another country, at the same time evoking both an attachment to and an estrangement from it.

Watching the final scene, I could only think, "What a bastard." One could imagine von Trier gleefully thinking up how best to upset his audience: wouldn't it be fun and completely different to make a musical about this great sacrificial mother and then hang her during the finale? It seems like a perverse theatrical shock tactic. Yet as the final number unfolds one finds oneself moved. The old punk aesthetic of publicly revelling in the display of the socially forbidden has been evident in von Trier's work since his debut The Element of Crime (1984).

If Dancer in the Dark is exciting to watch in itself, it becomes positively exhilarating when seen as a von Trier film, for the man seems capable of anything. The hallucinogenic visuals of The Element of Crime stayed in the mind long after the plot was forgotten. The hypnotic work on memory in Europa (1991), with its dazzling use of back projection, made it an extraordinary work of art cinema. In The Kingdom/Riget (1994), von Trier produced great television that wove black humour, a gothic story and social critique into a seamless and gripping narrative. Breaking the Waves proved his virtuosity with melodrama. Here, in spite of the dazzling technique on display, the use of jump cuts, zooms and so on, von Trier always lets his camera rest on faces, often in extreme close-up. As in Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc (1927), what the faces reveal is the film's truth; what they represent is a condemnation of the fact that a society would kill a person with the very virtues it claims to protect and uphold.

Björk's performance has been described as one that is 'felt' - she couldn't act, she could just be. Yet what is important is what she represents and conveys; how she achieved this is beside the point. And her performance is a tour de force: seeming plain one moment, exotically beautiful the next, she conveys the extraordinary intensity of Selma's repression. Indeed often in Dancer in the Dark it feels as if von Trier and Björk are two virtuosos on a collision course (Catherine Deneuve is often caught unawares by the camera, seeming to stand back, as if dazed and confused at the carry ons). Yet whether it's through collision or collaboration, art is what von Trier and Björk have succeeded in producing.