Primary navigation

In this first of a three-month series of articles devoted to British television classics, David Jays revisits Dennis Potter's haunted song album of a series, Pennies from Heaven, a forerunner in the European anti-musical tradition to von Trier's Dancer in the Dark

"Would someone with a hard face please protect me from those sickly and sugared old tunes?" television playwright Dennis Potter once begged. His imagination was steeped in songs from his childhood and adolescence in the mid-twentieth century. They provided the titles for most of his plays, and inspired his most distinctive work. In Pennies from Heaven, first broadcast by the BBC in 1978, popular song seeps into everyday life, momentarily transforming miserable circumstance. Instead of characters bursting into song as in a conventional musical, Potter has them mime to records of the 1930s, voicing ardent second-hand dreams.

Potter retained an ambiguous stance about popular songs, alternating between rancour and reluctant captivation. Interviewed by Graham Fuller, he spoke about the songs in his work, "half of which I hate... It's sometimes the ones that I hate most that can give me the most traffic, simply because I become aware of saying to myself, 'Why the hell is it in my head then?' Music clings to our memories because it lulls our fears, caresses our hopes. It lies to us, and we choose the lies that give most comfort.

The case of an American deserter and his lover who were found guilty of murder in 1945 provided the inspiration for Potter's plot (and for the 1989 film Chicago Joe and the Showgirl). Arthur (Bob Hoskins) is a married songsheet salesman with a fistful of dreams and an eye for the ladies. On a selling trip to Gloucester, he begins an affair with Eileen (Cheryl Campbell), a schoolteacher, who becomes pregnant. She loses her job and ends up on the game in London. They decide to cut and run, but Arthur is mistakenly accused of the murder of a blind girl, and is eventually hanged.

Miming (to a record of Al Bowlly, the principal sweet-voiced soloist in Pennies) was a technique that Potter had used briefly in a previous television play, Moonlight on the Highway (1969). It was still sufficiently unfamiliar for the BBC announcer who introduced the repeat run of Pennies from Heaven in 1990 to miss the point by saying "Bob Hoskins sings and dances..." Potter establishes the dissonant artifice of his method in Arthur's first song, which Hoskins mimes to a woman's voice. Beginning with his back to the camera, he opens the curtains of his comfortless marital bedroom, letting in golden sunshine as he spreads his crooner's palms.

Subsequent disjunctions between song and situation occupy a variety of comic registers, from charm (as Arthur glimpses Eileen through a harp on the music-shop counter) to madcap literalism (mist swamping the performers in 'Smoke Gets in Your Eyes') and blithe optimism, as hostile bystanders spin into coy chorus. Sometimes the illusion is slyly pelted with sound effects - a glass, tossed aside with debonair ease, smashes off screen - and occasionally illusion takes over completely, characters melting into the sunny illustrated covers of the sheet music. Arthur and Eileen sink into the rosy cover of 'Love Is the Sweetest Thing', even as he whips off her knickers.

Elsewhere, the match between feeling and song seems perfect. A compassionate torch song from Cheryl Campbell's soft-voiced teacher replaces a reading from the psalms at school assembly. Tuneful romanticism seems increasingly less apt as the narrative darkens, a delusive force that allows a café lecher to croon 'I Only Have Eyes for You'. There are fewer numbers after the bustling first two episodes; when Arthur is stuck in agonised discussion with his wife or mistress, you wish a song would interrupt to make things better.

Of course, Hollywood is no stranger to lip-synch, but prefers to paper over cracks in blissful illusion. When Marni Nixon provided the singing voice for Eliza Doolittle in My Fair Lady (1964), no-one noticed the join. Audrey Hepburn's huge dark eyes shone on the pillow as she vowed she could have danced all night, and Wilson's bell-like tone seemed a perfect fit. Potter and his director Piers Haggard, however, maintain the anti-illusionist emphasis throughout. There is no suggestion that the characters are actually singing - as in the opening number, the vocalist is often sharply inapt. And Tudor Davies' choreography, like the songs themselves, is heartfelt but limited, displaying few virtuoso touches, preferring the stilted conventional vocabulary of splayed palm, cocked wrist and modest wriggle.

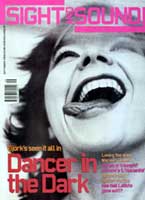

Like Pennies from Heaven, Lars von Trier's latest film Dancer in the Dark brings harsh reality smack up against brightly coloured escapism. Björk's heroine drudges through an unforgiving job and, like Arthur, ends up on death row, but the bleak narrative is intercut with spirited musical numbers. Like Potter, von Trier stands in a tradition of artists who acknowledge the energy of American musicals but have sought to accentuate the contradictions, to slip spanners into Busby Berkeley's gleaming works.

When Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev visited the United States in 1959, he viewed a rehearsal of Cole Porter's Can-Can at Twentieth Century Fox. The frothy dancing shocked him: "This is what you call freedom," he fumed. "Freedom for the girls to show their backsides to us is pornography... It's capitalism that makes the girls that way." Ah, that must be it, then. Certainly many European writers and filmmakers have been drawn to and recoiled from the model of the Hollywood musical, a sleek machine of melody, spectacle and hundreds and hundreds of girls. For the Weimar critic Siegfried Kracauer, the stage chorus line was a "machinery of girls", their choreographic precision like the working of pistons, their tap dancing a mechanical rattle.

Bertolt Brecht's imagination was fired by American literature and films. Long before he left Germany, he fashioned an imagined America: an unforgiving version of Chicago for In the Jungle of the Cities, the joyless city in The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny. Imperial Britain exerted a similar appalled fascination, providing the setting for his most popular experiment with musical form, The Threepenny Opera. "Nothing is more revolting," wrote Brecht, "than when the actor pretends not to notice that he has left the level of plain speech and started to sing." He enjoined actors to "speak against the music", and relished the fact that "the tenderest and most moving love song in the play described the eternal, indestructible mutual attachment of a procurer and his girl." Like Potter, he enjoyed sundering fact and comforting illusion, preferring a "separation of the elements". His composer, Kurt Weill, favoured a less dissonant model of montage, and these tensions were exacerbated when G. W. Pabst began filming The Threepenny Opera, producing what Brecht considered "a barefaced distortion". He unsuccessfully sued for control of the story, and the dispute inspired his formulation "Contradictions are our only hope!"

As Pabst assembled his film of beautiful shadows, another German musical created an icon of anti-glamorous charisma. Marlene Dietrich's lumpen Lola in The Blue Angel (1930) slouches to the front of the cabaret stage and sings 'Falling in Love Again' with deadpan disinterest. Moths cluster around the flame; the candle shrugs and tells them to expect the stench of burning wings. Fifty years later, Fassbinder presented an even more tarnished version in Lola (1981), where enchanting cabaret provides a literal front for municipal corruption.

Lola is the archetypal name for a twentieth-century siren. Another Lola's songs, in Jacques Demy's 1961 film of that name, are saturated with sadness. Melancholy is Demy's distinctive demystifying contribution to the musical, and his subsequent Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (1964) boldly separates story, appearance and mood. An unexceptional plot of provincial disappointment; a startling confectioner's palette of candy pinks and greens; and artless singing to Michel Legrand's plangent recitative, for which Catherine Deneuve's singing was dubbed. (Deneuve's reappearance, sans glamour, in Dancer in the Dark is surely no coincidence.)

Hollywood musicals also revelled in the tension between European severity and American entertainment. It is the subject of Silk Stockings (1957), a musical adaptation of Ninotchka, while Funny Face (1956) takes the battle to the Left Bank, where Audrey Hepburn's solemn ideologue finally mellows before Fred Astaire's happy hoofing. In Communist eastern Europe, Hollywood musicals provided uncomfortable ideological role models. Dana Ranga's captivating documentary East Side Story (1997) traces attempts to assimilate entertainment yet guard against capitalist menace. Soviet filmmaker Ivan Pyriev, for example, changed the object of desire, so that his agricultural workers exalt their tractors in song. Socialist musicals were still about dreams, still believed in a rainbow round the corner. Spectators bring their own devout longings to films; Ranga interviewed east European fans who worked in a bank and a sweet shop, wilful dreamers revelling in colourful escapism just like Potter's hero.

'I want the audience to be as disoriented as possible,' Potter told Kenith Trodd, his producer on Pennies from Heaven. Seeing the joins interested him, and he wedged disparate material into his plays to emphasise fractures. Discomforting identification is one such jarring element, whether the Singing Detective's severe psoriasis or the voyeuristic author in Blackeyes. Although Potter always denied autobiographical interpretation of his work, in Pennies from Heaven the murder for which Arthur unjustifiably swings was committed on 17 May 1935 - Potter's own date of birth. In the condemned cell, Arthur's wife asks where everything went wrong. "The day I was bleeding born," he replies.

Just as he sometimes denigrated the songs themselves, Potter's interviews gave an uncharitable account of Arthur, adulterous and deluded. Bob Hoskins, however, transforms the character through his absolute conviction in every contradictory moment. His narrow black eyes burn and flood, indicators of consuming emotion. Romance seeps into rutting and he refuses the discrepancy between rhapsodic melody and his blunt assertion, "It's all between the legs, innit." Hoskins makes Arthur the most fervent, least polished of the miming performers. He is a hefty dancer who sometimes loses his puff during a song, coming to a halt and flailing for fantasy.

"It's looking for the blue, innit, and the gold," he urges, defending his fervour for the songs. "The patch of blue sky and the bleeding gold dawn, and the light in somebody's eyes." Director Piers Haggard takes his cue from this for the songs which, unlike the numbers in the subsequent Hollywood film, do not take place in gleaming fantasy sets. The drab brown interiors are merely bathed in gold and blue light for moments of rapture and romance.

The audacity of Potter's juxtapositions remains breathtaking. In the third episode, Eileen reads about Rapunzel to a rapt classroom. She has just learned that she is pregnant, and the pupils hear a pained and lowering account of Rapunzel's prince, his eyes scratched out by thorns, and his weeping beloved. When they snigger about the unmarried Rapunzel having twins, a rattled Eileen snaps at them, only for the class to erupt into 'Love Is Good for Anything That Ails You.' The children grab toy saxophones and guitars as Eileen begins a roguish shimmy at the blackboard. The performance is charming, the blithe shift perfect for these cheerfully pre-moral kids and their fallen teacher, but the disjunction of tone is shocking. Despite the buoyancy, the classroom remains cramped, the children self-conscious.

In the 1981 film version, by contrast, Eileen is played by Bernadette Peters, an experienced Broadway performer, and we whoosh into a white-on-white fantasy classroom full of cavorting tots. Set in America, Herbert Ross' lavish movie was produced by MGM, who saw it as a potential return to the glories of their musical heyday. Ross achieves a series of ingenious production numbers (wittily designed by visual consultant Ken Adam, the master of opulent artifice), but misses the way songs slip through people's heads in the television series, threading the humdrum. In Ross' hands, brief reveries become full-scale fantasies.

Pennies from Heaven is set against the straitened economics of the 1930s, but largely chooses not to dramatise them. It was Hollywood itself, paradoxically, that found the perfect visual image for the effects of old man depression on bubbling musicality. Gold Diggers of 1933 bursts open with 'We're in the Money', chorines dancing around huge cardboard coins until bailiffs arrive to pull the plug on their show. In the television Pennies, Eileen mischievously hums, 'We're in the money,' a quotation to massage the awkwardness of going on the game; but Potter's real interest here concerns dreams repressed and shamed.

"Strange how potent cheap music is." Private Lives by Noël Coward provides the most celebrated line about popular songs, both rueful and condescending. Coward's lovers are without a scrap of innocence - in Private Lives, popular music tugs at the memory, but is analogous to the cocktails and Riviera honeymoons that betoken the protagonists' sophistication. In Pennies from Heaven, songs are tangled in a very different set of associations, innocent and bucolic. They become another form of aspirant storytelling and consolation, alongside hymns, psalms and fairytales. To Potter, they represent "the most generalised human dreams... a sort of religious yearning that the world should be whole"; these songs "are only diminished versions of the oldest myths of all in the Garden of Eden."

The dubious popularity of popular music is continually mocked, even by the shopkeepers whom Arthur supplies with sheet music. "People who whistle in the street are not the sort to come into my shop," sniffs one customer. A contemptuous headmaster churns out fodder for the coal pit rather than developing young imaginations: "What do they want with visions or trees shaped like diamonds, or any memory at all of the Garden of Eden? Cheap music will do. Cheap music. And beer. And skittles." Even though Potter is reluctant to mock the songs, Haggard's close-ups on kitsch popular products (Force cereal, Camp Coffee, Bisto) suggest a superfluity of disdain seeking an outlet. It's striking, too, how rarely we see the public's enjoyment of the songs - Arthur is his own most enthusiastic customer, and the only punter who appreciates his taste is Tom, Eileen's chilly pimp.

Potter's satire on censorious authority may be ludicrously overstated. What endures is his expression of yearning, as direct and luminous as the song lyrics themselves. "You all go around with grit and gravel in your eyes, and you can't see what a beautiful world it is that we live in," Arthur exclaims. "Shining, the whole place shining." And that's what the musical always offers: the impossible revelation of happiness on earth.