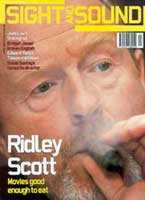

The Riddler Has His Day

The double whammy of Gladiator and then Hannibal has put director Ridley Scott right at the peak of his profession, but does he match up to the great auteurs, wonders David Thomson

In a recent interview for American television's 60 Minutes, Ridley Scott was about as enthusiastic as his gruff, laconic manner (and advanced age) would allow. He confessed that he was having a tremendous time, better than ever, getting up every morning to make movies. Could there be anything more fun in life? In fact, the man is 61; in effect, he seemed half that age. Is that the secret to carrying on in his very tricky business with his energy and panache - and with such pleasing results? Or are we observing a medium that promotes survival if a man acts half his age? And never gives a hint of that betraying defect - growing up - which is the one disqualification worse than growing old?

As one surveys the American film scene, it's hard to imagine that we will find ourselves celebrating 60-year-olds a decade or so from now. Age, experience and maturity are already anathemas; it can't be long before they cease to exist. People will remember Robert Altman as the last of an aberrant strain. More and more, the old are expected to behave like restless colts, or get out of sight. So it's quite remarkable to see the brindled veteran from South Shields rising to what is clearly a fresh peak, with Gladiator and Hannibal near-concurrent hits.

But don't ask too many awkward questions about how other people are faring in Hollywood as they reach Scott's age. Sixty is the marker looming up for (or already heavy on the shoulders of) Coppola, Lucas, Scorsese, De Palma, Schrader, Bogdanovich and Friedkin. The movie brats are being urged aside by the sheer rampant callowness of so many nerdy new waves. It's easier to recognise the historical perspective that said that any film-maker working past 60 had better be very strong, very determined or blessed with something like rare insight. Hitchcock was that age, more or less, when he made Psycho and The Birds - but it's an open question whether these were adult films or those of an old man trying to act young. Hawks was 62 when he did Rio Bravo. After 60, Huston made Fat City, The Man Who Would Be King and Wise Blood. Fritz Lang would do The Big Heat at 62. Sixtysomething Wilder did The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes; Fuller made The Big Red One and White Dog.

Still, I wonder whether those films weren't also green-lit by guys their age. Today, the decision and the funds depend on 35-year-olds who have likely never seen Rio Bravo or Fat City. Add a footnote: Max Ophuls, Murnau and Lubitsch didn't live to see 60, while Preston Sturges died at that very age after years of being adrift and after a directing fling of less than a decade - if one omits Les Carnets du Major Thompson. In short, are we asking too much to expect that anyone spends a career, or even a life, in film? Isn't there time off for good behaviour?

And Ridley Scott? Well, I'm writing a few days after Hannibal opened in the US. The reviews were mixed, but it's reckoned the film earned $58 million in its first weekend - only The Lost World Jurassic Park and Star Wars Episode 1: The Phantom Menace have beaten that, and one would like to hope that rather more of their customers were innocent babes (an American marketing concept) than parents allowed to see Dr Lecter's cookery class. Above and beyond that, Gladiator - which amassed $190 million in 2000 alone - has raked in 12 Oscar nominations, including best picture, directing, script and actor.

Ridley Scott has not yet won a thing. Indeed, his lone nomination hitherto - for directing Thelma & Louise (1991) - lost to Jonathan Demme for The Silence of the Lambs. This is the moment to stress - without so much as a trace of guilt - how much I like Ridley Scott's work. Even the sillier projects - such as G. I. Jane (1997) and Someone to Watch over Me (1987) - are made with relish and a boy's delight in the surface prettiness of things (you could even say that Someone is about falling in love with an apartment). I'm never bored or bewildered by Scott (OK - 1992's 1492 Conquest of Paradise gets very close), in the same way that for a good 10 years or so one could count on Michael Curtiz to be entertaining. Don't regard that remark as patronising - just look at The Adventures of Robin Hood, Angels with Dirty Faces, The Sea Hawk, Yankee Doodle Dandy, Casablanca, Mildred Pierce and The Unsuspected some weekend and recognise the sheer fluency and movie-ish oomph of an old pro. Curtiz directed those seven films in a 10-year span from 1938 in which he made 27 pictures altogether. Scott, so far, in 25 years has made 12.

What I'm trying to say is that there's no shame if Ridley Scott is only as good or as interesting as Michael Curtiz - he simply doesn't get the practice (or live in the same context of competition). That's exactly why I like Hannibal more than some people do. It's a very cunning, very adroit retreat - away from impossible horror and camp mockery, towards entertainment - to ensure that a sequel stays watchable instead of advancing down one of the several crazy (and hideous) dead-ends available. If half the stories of its different directions along the way are true - with two strong writers (if you'll excuse that term) and a narrative commercial/aesthetic quandary as to whether Jodie Foster would do the picture (or it could be made right for her) - then Scott deserves all the gratitude of those who hired him. He brought the movie in. It works. It's smart, good-looking, sexy, fun.

But if you took the Demme film seriously, and have ever regarded the Thomas Harris books in that way (and by "seriously" I mean as if they were receptacles for intelligence, ideas and concentrated argument), then Hannibal is to be regretted. I'm more relieved than hurt because I thought The Silence of the Lambs was a collection of excruciating tricks unworthy of Jonathan Demme and essentially dependent on torture, cruelty and putting demented behaviour at the heart of the story. Demme was too good to spare us the pain; and the genre and the medium were too greedy to by-pass it. Lambs was an ordeal to watch and it was harder than ever to suppose that its gouging impact might not disturb fragile, damaged or already dangerous minds - I'm thinking of the kind of people one meets at the movies these days.

No, I'm not saying that Lambs might have been cut, censored or banned - no matter that not too many years earlier no one would have dreamed of making it. Censorship is a more reliable evil than the chance of a movie inspiring some unsteady mind. But if you don't think that's a risk Lambs takes - with nothing else of a compensatory nature - then I think you're kidding yourself and adding to the peril.

Of course, Hannibal is camp, and not just cooked but marinaded first - whereas Lambs was raw and terrifying. I give thanks for that relief, and would only note in passing how far it illustrates a dire problem for mainstream narrative cinema: that the story that worked on its own terms, that held its own reality, yesterday, becomes self-parody tomorrow. It's not just that you couldn't do Casablanca or Mildred Pierce now without making them pastiche. It is, literally, that Hannibal Lecter has become such a household joke that he can't be dreadful again. It seems clear that Anthony Hopkins and Scott saw that, and planned accordingly. That's how the movie was saved. But don't forget how surely this built-in slope is destroying all the main forms of narrative. Talk to children and teenagers today: they believe that all movies are innately silly, self-mocking and ironic. They no longer hear, feel or see a natural gravity - or the chance of it - in movies.

So Scott turned Hopkins loose after a decade in which the actor had had to 'do' Lecter for every boy, dog and talk show he encountered - while finding that sometimes they did the doctor better themselves. So Lecter now is Capote-ish, large enough for cloaks and Borsalino hats, and capacious enough as aesthete, perfectionist and scholarly scold for his disdain to extend over the rainbow. He is the kind of deliciously wicked uncle Clifton Webb promised as Waldo Lydecker in Laura. As fruity as summer pudding. Is the character gay? Well, not in any sense that would alarm audiences or befuddle political correctness. But by the code of, say, the 40s - yes, indeedy.

What's clever about this smuggled perfume is the fragrance it brings to Lecter's feeling - that sniff he gave her once - for Clarice. Demme grasped that straw, and it was alarming 10 years ago that Lecter had smelled out something Starling didn't yet know: that she was sexed. What made that thrilling, or menacing, was Jodie Foster's placing of agent Clarice Starling in a sexual out-of-bounds. Her FBI woman was so very numb and unaware, even if she was of legal age. It was when Lecter looked at her that for the first time she got an inkling of what sex could mean. The rest of the world dreamed of cannibalism, but Foster's eyes widened with the sudden vision of cunnilingus. No, not even the vision - the sensation.

I don't know what happened on the road to Hannibal. Maybe Ms Foster the actress prevaricated. Maybe she thought to herself that if they needed her they'd have to pay a fortune beyond even producer Dino de Laurentiis' reach. Or maybe she was playing with herself, because something of the Clarice-Lecter intrigue had really shocked and horrified her. Perhaps she guessed that the outrage would turn camp, and counted herself out; she's smart enough to know how limited her humour is on screen.

So Scott went another way - towards an older, more sexually experienced woman. Julianne Moore looks like a handsome hippy 40; she also looks and reacts like a woman with few fears or illusions left about men. In becoming isolated at the FBI because of her professionalism, even her perfectionism (the thing she really shares with Lecter), she's evidently had enough bad affairs to prefer the company of her computer. But Moore saw the old movie, understood the flicker of attraction, and knows Lecter will lead her to the dance. And she's drawn by the prospect, just the chance, of being eaten.

Looked at that way (I could find no other), Hannibal is sexy, dirty, naughty, funny and knowing. Indeed, it has enough to let you notice that Lecter and Clarice are a cartoon version of Humbert and Lolita. It's not enough to make the film intelligent or interesting - and Nabokov's novel is all of that. But it keeps a two-hour picture engaging. The laughs and the gotchas are well paced, and it would take a very earnest soul not to be tickled by the hair-raising act that befalls Ray Liotta. Was there ever a cockier look so oblivious to things happening upstairs?

Then there is Italy, or Florence, which Scott does with the empty flourish he has commanded all his career - as if the settings were ready to be eaten. In this instance there could be a vein of comedy in that, a kind of scenery-chewing hungry tic in Hopkins so he can't pass a quattrocento throw cushion without having a nibble. Long ago, in that first, very arresting picture The Duellists (1977), Scott showed his total immersion in the visual language of advertising. Indeed, I have seen no evidence since that his notion of beauty extends one inch beyond the urge to depict landscape, buildings, furniture, clothes - come to that, anything - as if it was purchasable. And so in The Duellists, just as one was marvelling at the inane, implacable bond of honour and torment that would forever tie Harvey Keitel to Keith Carradine, there was always the intense but irrelevant urge to get oneself a property in the Dordogne.

Let me try to be more precise, and properly angry, about this. The look of advertising is meant to be ravishing and seductive; it is, if you are persuaded by such words, handsome, spectacular, lush, elegant... rich, expensive, valuable, luxurious, edible. It is not beautiful, for the plain reason that such eye-pleasing attributes as form, balance, chiaroscuro, depth of focus, harmony of colour and so on are all absolutely poisoned by the function of advertising - to make us envious or insecure about not having this golden thing. So when you look at The Duellists you want that magic-hour location, whereas when you look at Renoir's Partie de campagne you feel the interaction of human nature and nature itself and thus the seasonal round in which all living things must change and wither. It's the difference between a sense of possession and an admission of mortality, or tragedy (for nothing, truly, is possessed for long).

We know very well that Ridley Scott and his brother Tony have had a commercials company for years. Those are details on a professional résum´e, and enough to indicate the lamentable thrust of their art-school training. That's their choice, and they're welcome to it. It has surely added to their fortune. But the movies belong to all of us, and someone needs to insist that there's an oceanic gap between the beauty to be found in Renoir, Fritz Lang, Antonioni, Nicholas Ray and Ophuls and the modern lacquer that's glibly described as "beautiful photography". Indeed, granted the advances in technology available to photography nowadays, the majority of cinematography we see deserves to be assailed as slick, lazy, anonymous and "lush" compared with the movie styles of the 40s. "Beautifully photographed" is a term that merges characterless proficiency with the kind of buying eye that so undermines Ridley Scott as an artist. For the 'beauty' in Renoir, Antonioni and the others is not just a way of seeing. It's a way of feeling about nature, structure and the lives led in those settings. It's organic, whereas Scott's eye is a decorative coverlet draped over a world the director doesn't trouble to probe.

Scott's cheery ignorance reminds me of an occasion, years ago, when I taught John Berger's Ways of Seeing in an introductory course on film, or looking at the world. Ways of Seeing was the book that came from a television series in which Berger attempted to analyse the ideologies (or the lack thereof) in modern notions of seeing and attractiveness. I discussed his annihilation of advertising, and I think - with the advantage of his examples - I made a decent job of it. But at the close of the lecture, a student came up to thank me. Prior to that day, he said, he had felt lost and aimless, uncertain what to do with his life. Now the cloud had moved aside. Sun filled his face. He would go into advertising. I'm sure he's there now, with every right and reason to reckon he's one of the élite shaping the world's understanding of itself.

And if it strikes you that Gladiator, say, is beautiful - as opposed to just burnished, collectible and in fine condition - so be it. I found Gladiator a sumptuously empty film. Monotonous in plot, muddled in action and daft in its ending, it was determined to knock out the eye while neglecting the mind. It was 'about' nothing except a set of clichés of what Rome was like. But it has 12 Oscar nominations and a patina that normally requires centuries of slavery. It's not a film about Rome, but a wallowing in the Roman look.

All too often such disastrous 'stylishness' besets Ridley Scott. Even what I take to be his best and most interesting pictures - Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982) - are as much concerned with the design of their future places as with the quality of their people. Scott has an escape clause there: the more our world adopts his code of beauty, the less human personality will mean - so the intriguing diminution of human character in these two movies fits with the look of things, and especially their mannered shabbiness. Whether that was intended or comes as accidental bonus, you must decide. Whatever the answer, Scott's facile eye is easier to take with imaginary landscapes or decor, so there's something both magical and sinister in the baroque dankness of the future Los Angeles and the fossilised orgy of the dead planet where the alien lurks.

Twice - with Ian Holm in Alien and Sean Young in Blade Runner - Scott handled the fascination and pathos of a humanoid not quite all there, yet seeming to lead the way for the rest of the 'full' humans who were already enervated or drained. I've never been convinced that Scott is actually the feminist he's credited as, but still he judged the maturing of Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) in Alien very well. Yet it seemed typical, at the end, that he saw no reason not to titillate us with Weaver in her sketchy (designer) underwear while also allowing the large intellectual prospect that the alien had fallen for her character. Alien is a very tidy, enclosed study in claustrophobia (it ends in the safety of a sleeping tube), and a satisfying film about a heroine in distress. But Scott deserves more praise because he had felt out the ominous sexual charge of the series to come, and captured the ambiguity of loneliness in space.

To argue that Scott sometimes neglects people in his enthusiasm for 'cinema' or entertainment - that he's more interested in shooting things than in revealing depths - is rather as if someone were spoilsport enough to notice that despite the sweet movie-esque coherence of Casablanca, its attitude to people is adolescent and superficial and thousands of miles away from real war and suffering. Was the war ever quite so much fun? And there's always been a trend in film criticism eager to say that doesn't matter. The same enthusiasm saw the real relief of Casablanca as the film opened and declared with wide-eyed innocence - the same state of mind ready to think Paul Henreid has been in a concentration camp as opposed to a country club - that surely films did matter and touch history. Whereas, the 'reality' of Casablanca is the story of so many strange refugees - with Conrad Veidt and Dalio the real, heroic victims - gathering together under the warm Warner lights to make a romance. Thus the monstrous villain and the droll sidekick were actually actors who had been deprived of their artistic heritage - and in the case of Dalio that world was one of the finest ever known.

All I am trying to suggest here is that Ridley Scott makes romances - and, for myself, I enjoy them very much, at the level I do the best films of Michael Curtiz. His actual unawareness of human depth is regularly masked by his very acute casting instinct. Remember, long ago, that he guessed what Sigourney Weaver might become - saw not just that she was pretty and smart, but tall, lofty, a touch aloof and chilly, with the seed of truculence, like a young woman raised by the military. He knew that in casting such antithetical figures as Keitel and Carradine (the hipster and the obsessive), he might be home already. He relaxed Geena Davis, he discovered Brad Pitt, he had a rapport with Ian Holm, he felt the pain in John Hurt and knew what might be causing it, he knew where Jeff Bridges' rather mortified heroic nature could be found. He casts very well indeed, and reminds us of the old Hollywood adage: if you cast well, you can leave the actors to it.

But it is up to us - I mean the very small resistance movement ready to read or write about film - to argue that this is not enough. In proposing the equality of Ridley Scott and Michael Curtiz, I am seeking to draw our attention to how little of a subject we have left.