Sick City Boy

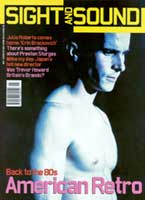

As the New Economy boom (and seemingly imminent bust) reminds us of the "greed is good" 80s how does American Psycho work as social satire and what does it have in common with Stanley Kubrick's portrait of thuggery A Clockwork Orange, asks Nick James

In Mary Harron's new movie version of the cult novel American Psycho the first victim is an African-American man sitting in a New York alley with a paper cup in front of him, homeless and hungry and smelling of shit and booze. Wall Street worker Patrick Bateman taunts him with offers of money and food, then hisses into his ear "Why don't you get a job?" before stabbing him in the stomach. This is lighter treatment than the same beggar receives in Bret Easton Ellis' original 1991 novel, where Bateman's blade "pops" his retina, cueing a gruesome description of eyeball matter oozing down his face.

An Irish drunk lying on his back in a tunnel singing songs of the old country gets it first in Stanley Kubrick's adaptation of Anthony Burgess' A Clockwork Orange (recently released on UK screens for the first time since 1972 when Kubrick withdrew it after several 'copycat' crimes were laid at its door). Stuck in a dystopian future, his misfortune is to be visited by young British yob Alex and his droogs on the lookout for some ultra-violence. "I could never stand to see a moodge all filthy and rolling and burbing and drunk," muses Alex before he and his pals lay in with assorted weapons.

Street people are the hapless victims in this kind of social satire not because they make us feel guilty about our relative wealth and privilege but because they are out of the loop, beyond the pale, non-participants. They can't be consumers of the critique, only targets of its messenger. Bum-killing aside, these two films otherwise bear little comparison. Both are adaptations of satirical novels about young psychopaths who are meant to represent the ills of their age. Both show women as perpetually available objects for mistreatment (though Harron has them show their contempt for Bateman's inanity).

Thereafter it's all contrast: A Clockwork Orange is a 60s novel inspired by a 50s phenomenon (teddyboy gangs) set in a future which Kubrick renders as a 70s sex-and-violence fantasy married to a somewhat paranoid vision of brain-washing as a treatment for young offenders. American Psycho is a 90s novel set in the late 80s which Harron has lovingly recreated as a fetishised hall of mirrors for mirror men. Kubrick's film attacks a Britain of rigid and blind institutions which are no longer recognisably with us. Harron's lampoons the denizens of US finance houses and their rabid boomtown consumer culture. One young male protagonist is at the bottom of the social heap, the other at the top. Is there anything else that links these films other than the vicious survival-of-the-fittest ethos of their central characters? The short answer is yes, but to follow my thread we must do like Mary Harron and revisit the 80s.

The flaunt-it, goldrush aesthetic of the 80s was satirised almost from the outset. Culturally it was a pompous decade that took its fantasies of glamour extremely seriously - think on the one hand of the po-faced New Romantic art crowd straining for a post-Bowie, post-punk, post-gender utopia in clubland, and on the other of the brokers and traders with their anal focus on 'correct' forms of consumption. In the US these were two sides of the social coin and the twain met in the clubs of New York. It was a time ripe for ridicule, irony and sarcasm, the heyday of postmodernism. But, being the 80s, it attracted serious ridicule, irony and sarcasm.

American novels of cocaine abuse and anomie among the well heeled took the zeitgeist limelight. Jay McInerney's 1984 Bright Lights, Big City concerned the free-fall of a magazine fact-checker lost in clubland and dumped by his model girlfriend. Its hero's dilemma begins when he finds himself in a club in the early hours where "the bald girl is saying this used to be a good place to come before the assholes discovered it." The question here is whether the narrator is one of the assholes. Given the book's self-lacerating tone, maybe he is, but the girl with the shaved head is also "emblematic of the problem... Her voice... is like the New Jersey State Anthem played through an electric shaver." The usual emblematic bum is not a victim here. He doesn't turn up until the last chapter where he confers a blessing on the repentant hedonist with his bleeding nose as he staggers back to sane bourgeois comfort and someone more conventional to look at than the bald woman.

Ellis' 1985 fiction debut Less Than Zero followed in McInerney's footsteps. It's about a rich West Coast boy trying to decide whether or not to let go of his feckless, coke-addled teen milieu and go back to college. This was satire so discreet it looked like celebration. Both books are firmly and unapologetically set among the well off. They describe and perhaps promote the anomie of limitless self-gratification and, despite the fall each protagonist experiences, I would guess they were hungrily consumed by the envious. Movie versions of both emerged in 1988, but the novels had been defanged to fit the earnest mould of the Brat Pack movie.

The critique sharpened as the me-decade rolled on and the fiscal grotesqueries of Milton Friedman, Margaret Thatcher, Donald Trump and other 80s icons became harder to stomach. The keynote movie was Oliver Stone's Wall Street (1987) with its anti-slogan "greed is good" uttered by its resident ogre, corporate raider Gordon Gekko, the archetype of the 80s money man. As Gekko Michael Douglas jutted out his chin and made cobra eyes at the victims of his ruthless workaholism. His other oft-quoted utterance is "Lunch is for wimps." Aspects of the Gekko creed have returned to haunt us today with the new boom (and looming bust) in cybershares. In the forthcoming movie Boiler Room, which is about a judge's son who works in a 'chop-shop' (a company that trains people to hard-sell worthless bonds), the team of traders recite Gekko's dialogue word perfect while watching a video of Wall Street. Like, say, In the Company of Men and Claire Dolan, Boiler Room doesn't feel like a new take on hard-edged city life, but an 80s film made now.

In the same year Wall Street was released, Tom Wolfe, a scion of 70s New Journalism who had switched to novel writing, put out The Bonfire of the Vanities. Wolfe's ambition was to draw a vast portrait of New York's different social levels on a scale worthy of Dickens or Zola. His 'hero' Sherman McCoy was a 'Master of the Universe', a WASP bond trader who takes his Mercedes down a wrong turning and ends up in the Bronx where, by accident, he finds himself accused of killing a young black man. It's worth quoting a little of Wolfe's prologue, which enters the mind of a Jewish mayor of New York trying unsuccessfully to face down a rebellious televised Harlem crowd, to get the full flavour of his race-paranoid thesis: "They [the WASPs] won't know what they're looking at [on TV]. They'll sit in their co-ops on Park and Fifth and East Seventy-second Street and Sutton Place, and they'll shiver with the violence of it and enjoy the show. Cattle! Birdbrains! Rosebuds! Goyim! You don't even know do you? Do you really think this is your city any longer? Open your eyes! The greatest city of the twentieth century! Do you think money will keep it yours?" If the Brian De Palma movie failed to make Wolfe's novel feel relevant, a more succinct take on WASP redundancy was found in Whit Stillman's 1989 Metropolitan which had its well-heeled gentry go gentle into that good night of acceptance.

What all this 80s them-and-us social satire reminds me of is the way the spectre of 'the masses' haunted modernist writers in the early 20th century as described in John Carey's book The Intellectuals and the Masses. The growth in population and literacy that led to the advent of mass culture was greeted by a Nietzsche-inspired vein of disgust and horror in the writings of such highbrow authors as H. G. Wells, T. S. Eliot, F. R. Leavis, W. B. Yeats and Virginia Woolf. Carey argues that "the principle around which modernist literature and culture fashioned themselves was the exclusion of the masses, the defeat of their power, the removal of their literacy, the denial of their humanity." But, he concludes, "What this intellectual effort failed to acknowledge is that the masses do not exist." Literature constructed the idea of the masses by "the imposition of imagined attributes" - the consumption of newspapers and tinned food, for instance.

What you consume has been the marker of who you are in literature for the better part of the 20th century. And long lists of what Patrick Bateman consumes notoriously make up a large amount of Ellis' novel. What we consume is also a part of him - it's impossible to read Bateman fully without knowing who Sherman McCoy and Gordon Gekko are. McCoy gets a brief namecheck in the novel and Gekko a walk-on part, postmodernism now being in full swing. All this self-reference poses problems for the film-maker, however, who can't rely too heavily on an interior voice.

Sufficient distance from the 80s allows Harron to treat Ellis' gruelling subject matter with a greater sense of fun. She takes a more broadly comic, arm's-length view of Patrick Bateman - there's almost a hint of Austin Powers about actor Christian Bale's willingness to camp it up. He looks unreal in a very 80s way - a lot like Christopher Reeve as Superman (Nietzsche again?). In the book mockery of Bateman's status-obsession is a sly matter of shifting tone - it leavens the intense babble of bloodlust inside his head. Harron makes lampooning 80s man as a creature of surfaces her grandstanding play.

For Harron it's about getting the surfaces right. (Like Claire Dolan, her film has a cold, metallic, surgical gleam.) Bateman's apartment is a white sepulchre, a plinth for his statuesque "hardbody". A mantra-like list of bodycare products is delivered in voiceover as Bateman applies them in his shower: a nominally straight man showing a super-feminine level of interest in beauty care as he prepares for the intensely masculine world of Wall Street. It's as if he's putting on armour. The portmanteau word "hardbody" is just one of a series of puns to do with the vulnerability of the flesh - for instance, Bateman works for a company called Pierce and Pierce. A "hardbody" is not only an 80s creation of Nautilus and Stairmaster but also Bateman's nickname for the kind of woman he needs to find - one invulnerable to his wish to stab and cut.

Harron refuses any empathy with Bateman. She isn't interested in the causes of his internal crisis. She plays down the violence and plays up Bateman the bore, who likes to explain in detail his musical preferences to uninterested whores. For her, as reported in this magazine (S&S July 1999), Bateman is "a symbol" who "represents the craziness of an era, all its psychoses wrapped up in one person - obsession with clothes, obsession with food, obsession with his skin." The problem with this approach is that it weakens the satirical attack. You immediately feel her art-crowd contempt for the cityboy. Preaching to the converted, the film panders to the average movie fan's disdain for 'suits' in a way the novel avoids. You'd think the art crowd had no part in this 80s obsession with clothes and restaurants, that they were untainted by greed and ambition. This is a failure to acknowledge the roots of the novel's cult success, which lie in its complicity with the idea that there's something of Bateman in many young men. You can hear the incomprehension when Christian Bale says of the cityboys he met while researching the role, "For a lot of them, it's their favourite book. They just don't seem to get that it's laughing at them." Observations which posit the question, is the novel also a failed satire?

To understand what's missing from Harron's film we need to go back further, to the mid 70s. Ridicule, irony and sarcasm - the weapons of satire - were the first recourse of UK punk rock, which borrowed its sound but not its lyrical content from US punk rock. Its key slogan was "no future" and its style was a co-option of Dickensian urchin rags and sex-shop bondage gear - what could be more satirical? The link between the sneering of A Clockwork Orange's Alex and Johnny Rotten's ranting delivery is obvious, and rhetorically they are manifestations of the same voice of British youth discontent, of a generation that realised the manufacturing industry was a dead end many of them could be stuck in. It's hard in the neat and tidy new millennium to remember how large crowds of unruly youth did gather in the 70s. You only have to watch footage of the pitch invasions that invariably followed soccer matches or the pitched battles between mods and rockers to realise how much things have changed. They've changed too in New York, where Mayor Giuliani's "zero tolerance" policy swept visible evidence of the 'underclass' away from the streets, keeping Tom Wolfe's lurid vision of a Third World invasion at bay for the time being.

With the 80s came an unprecedented interest in the history of youth style and rebellion that went hand in hand with the new fascination with the rich. Writers who came out of punk in the UK turned their attention to style. The birth of such style magazines as The Face and ID coincided with marketing companies' and academics' attempts to understand Subculture the Meaning of Style (to use the title of Dick Hebdige's then-essential book). Links were established between the 50s teddyboys who inspired A Clockwork Orange and the 'gorblimey' brokers, the cockney boys who had been allowed on to the trading floors of the stock exchange. Brash, arrogant, brutal and self-possessed, they were matched by a generation of post-punk writers who would eventually dominate British journalism, creating a new grub street of vicious satirists prized for their irreverence, though eventually used to bolster a very British philistinism.

The UK punk voice had its impact on Ellis too. Less Than Zero was named after a 1976 Elvis Costello song from the album My Aim Is True. This was the album that defined what was then called New Wave music - the tidier, more intellectual pop that ran parallel with early punk - but Costello had also co-opted the Alex sneer, and some of his lyrics, particularly on the Armed Forces album, have the tang of Burgess about them. On the US side of punk, Talking Heads, by their very neatness, were also tidied into the New Wave category, but their most requested song 'Psycho Killer' came from their early punk moment. Listening to the lyrics it's easy to imagine it was one of the starting points for American Psycho. Indeed, Talking Heads are mentioned more than once by Bateman, somewhat against type since the rest of his musical taste is hilariously outré.

In particular the middle verse of 'Psycho Killer' - "You started a conversation/That you won't even finish/You're talking a lot/But you're not saying anything/Well I won't say nothing/My lips are sealed/Say something once, why say it again" - perfectly summons up Bateman's attitude to the social round in New York. He can't say anything because what's burbling on and on in his head is unsayable. Heads singer David Byrne's nervy voice edges to breaking point, then relaxes as he delivers the perfect 80s epitaph: "We are vain and we are blind/I hate people when they're not polite."

The voice in Bateman's head is a fucked-up rich kid's counterpoint to Alex's. It speaks of the collision between smart preppy kids and street-smart punks. It wants to destroy the passer-by, but not because it wants to be anarchy - it already is. Ellis' voice is complicit with Bateman's, its endless riffing on product labels a cry for help you feel the author shares. But effective satire requires the satirist to take up a morally superior position and Ellis, being helplessly of the demi-monde himself, can't find that position any more than Harron can.

If spectres of authority haunt A Clockwork Orange, there are none to speak of in American Psycho. The only cops we see all die when Bateman, having apparently killed too publicly, shoots at their patrol cars and they explode. Harron treats this on-the-run sequence like a Simpson and Bruckheimer movie, with Bateman an untouchable action hero. It climaxes with Bateman hiding in his own office phoning in a full confession that will later be treated as a joke by his lawyer. It's clear that Harron believes Bateman to be a fantasist, that he may not in fact have killed anyone except in his own mind - and since Bateman is a notoriously unreliable narrator there's plenty of evidence to back her up (he tells us things he can't possibly know, experiences ridiculous identity mix-ups, former victims turn up and are polite to him).

Violent movies are fed to Alex by state officials, who have injected him with some new drug as they pin back his eyelids and keep his eyeballs lubricated. The drug means that if he tries in future to become violent his recall of these movies will make him nauseous. Violent movies are a staple diet for Bateman - we know he watches Body Double and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and that he always has some videos he needs to return to the store. It's the movie in Bateman's head that's making him sick. And since the 90s were, by general consent, a continuation of the 80s by other means, you have to wonder where Bateman is now, and how he's channeling all that rage and sickness.