Obituary

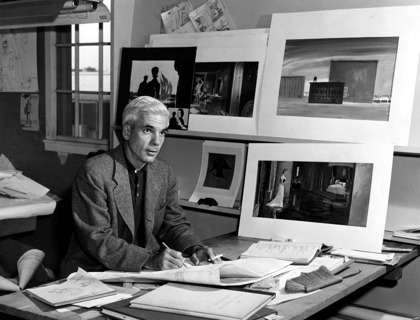

Robert Boyle

Photo courtesy Photofest

Production designer

10 October 1909–2 August 2010

Had he not graduated in 1933, Robert Boyle might have followed his dream of designing houses and skyscrapers. But during the Great Depression, building illusions was the only job going for a budding architect in California, and it was at Paramount that Boyle found refuge, working as a sketch artist under Hans Dreier, the production designer responsible for von Sternberg’s atmospheric, shadowy sets.

Yet over the following six decades, Boyle became a production designer known not for his extrovert style, but for his expert craftsmanship, his technical innovations and his eye for detail. “It’s very easy to make films that show off design,” he would later warn. “The problem is to exert some discipline.” In his view, his job was to create “a total physical environment that interpreted the script”. Or as he more tersely put it, the production designer was the one who “knew how to get the film done”. And throughout his long career, Boyle got 87 of them done, working for directors as varied as Alfred Hitchcock, Bud Boetticher, Norman Jewison, Douglas Sirk and Sam Fuller.

It was with Hitchcock that Boyle received his break, on Saboteur (1942). With a tight budget and the outbreak of war preventing the crew from using any actual military factories, Boyle improvised using storage bins with sliding doors and painted backings. Meanwhile a black swivel chair came in handy when Norman Lloyd needed to meet his fate spinning to the ground from the top of the Statue of Liberty.

If suspense was Hitch’s trademark, deception was Boyle’s. For The Birds he oversaw the painstaking construction of a single God’s-eye-view shot of seagulls swarming over a burning petrol station, from 33 individual bits of film. Interestingly, Boyle’s earliest cinematic memory was one of avian horror: as a small boy he was terrified by an eagle carrying off a child in the 1908 silent Rescued from an Eagle’s Nest.

However, if The Birds was Boyle’s technical tour de force and, as he would later admit, the craziest, most complicated project he ever worked on, North by Northwest provided the most dangerous moments of his career. Long before Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint climbed down Mount Rushmore, Boyle was precariously lowered down Lincoln’s face on rusty cables in order to photograph the site for backings and models after filming was forbidden there.

North by Northwest also proved that Boyle could let design triumph. We might have been absorbed by Cary Grant’s efforts to spy on James Mason, but it was Vandamm’s sleek, hilltop villa that really stole the show. Inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater house and designed by Boyle to be “the perfect jungle gym” for Grant to climb up, it was actually constructed on stage five at MGM – a fact that has always disappointed fans keen to visit the ultimate villain’s lair.

For Boyle, just like Hitch, reality and shooting on location were best avoided. There were some exceptions: he and Jewison scoured Eastern Europe with a tape recorder, playing tunes from Fiddler the Roof in remote villages to gauge how suitable they might be for the musical’s film adaptation (before Boyle decided to build the whole Jewish shtetl in Yugoslavia). Meanwhile, working on Richard Brooks’s In Cold Blood, Boyle used the actual Clutter house to chilling effect, and also built a perfect replica of the Kansas penitentiary’s gallows for the final scenes.

It seems though that Boyle was most at home building in the studio, where reality could be fashioned with the utmost control and precision. Jewison, depressed after not being able to secure a real submarine for his 1966 comedy The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming, promptly received a full-size fibreglass and styrofoam version. Under Boyle’s eye, Universal’s backlot contained all manner of cities and landscapes, from turn-of-the-century Chicago for Jewison’s Gaily, Gaily (1969) to a fully heated swamp (so the actors didnt get cold) in Cape Fear (1962). For Boyle, a self-christened “relic of the studio system” and one of the last designers to know all the secrets of the Golden Age’s hidden arts, Hollywood really was “a place where you can imagine whatever you wanted”.

For more information on Boyle, see Daniel Raim’s documentary on the production designer The Man on Lincoln’s Nose as well as Raim’s tribute to the craftsmen of Hollywood past Something’s Gonna Live.

Isabel Stevens

See also

Double Take reviewed by Jonathan Romney (April 2010)

Muraki Yoshiro, 1924-2009 remembered by Stuart Galbraith IV (March 2010)