Primary navigation

More than just a homage, Johan Grimonprez’s extraordinary montage uses Hitch’s mischievous TV appearances as the launch pad for a brilliant riff on Cold War politics and the idea of the double. By Jonathan Romney

As all Hitchcockians know, a macguffin is the object of desire in a narrative – the thing that everyone is chasing, but that really has no function except to make the story happen. Hitchcock defined the macguffin in a famous anecdote.

A man in a train is asked by another passenger about the mysterious object in the luggage rack; he explains that it is a macguffin, used to hunt lions in the Adirondack Mountains. But there are no lions in the Adirondacks, the other man objects. To which the first imperturbably replies, “Then that’s no macguffin.”

In Double Take, Alfred Hitchcock himself is the macguffin – the protean, elusive mystery around which Johan Grimonprez’s extraordinary montage revolves. Hitchcock’s narrative strategies, thematic obsessions and persona have long fascinated artists: Pierre Huyghe and Douglas Gordon are among those who have recently attempted entire or partial remakes – ‘doubles’ – of Hitchcock films. Now the Hitchcockian theme of doubling is the basis of this hybrid film by Belgian film-maker, artist and academic Grimonprez, who previously explored the topic in his 2004 short Looking for Alfred, about his search for Hitchcock lookalikes.

In Dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y (1997), Grimonprez used archive footage to contemplate our era through a chronicle of airline hijacks. That film also involved doubles – it was informed by Don DeLillo’s idea of the terrorist and the novelist as twins, both engaged in (re)writing history – and itself pursued parallel careers on the cinema and gallery circuits. Grimonprez’s new film again plays a double game: Double Take is deadly serious in its scrutiny of politics, anxiety and the media, but it’s also a witty entertainment that responds to Hitchcock with much of the master’s own lightness and mischief.

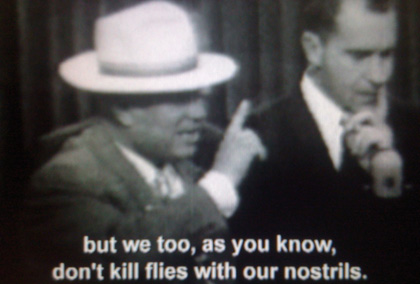

The film’s several strands are all underwritten by the theme of the double. In a mini-history of the relationship between Russia and America, Grimonprez follows these rivalrous twins from the early years of the space race, through the Cuban missile crisis, to Reagan’s ‘Star Wars’. A key point in this ongoing face-off is the televised 1959 meeting between Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev and Vice-President Richard Nixon, the so-called ‘Kitchen Debate’ (it took place in a model kitchen at a Moscow trade fair). When Nixon claims that the miracle of television gives America the technological edge over the USSR, the bald, tubby showman Khrushchev (a Hitchcock double, of course) responds with cheerful and flamboyant derision. The American can only grin helplessly through his opposite number’s routine, as Khrushchev shows just who is the master of television here.

Another strand follows Hitchcock’s career as television clown – both a master of prime time and its mocker. The director’s comic introductions to his US series Alfred Hitchcock Presents prove his command of the medium, while simultaneously deriding it. An Englishman abroad, at once inside Hollywood and foreign to it, Hitchcock was in an ideal position – with the diplomatic immunity of a cultural ambassador – to satirise America and its media. In his introductions he is particularly scathing about commercials, no doubt to the horror of his sponsors. The ad break is characterised as the enemy of suspense: it is designed, Hitchcock warns his viewers, “to keep you from getting too engrossed in the story.” In his own tantalisingly fragmented narrative, Grimonprez includes a series of commercial breaks – vintage TV ads for Folgers instant coffee in which the American housewife is terrorised with the threat that her husband will leave her if she can’t provide a decent java.

Patriarchal beyond the imagining of Mad Men, these hilarious, horrifying ads signal the primacy of anxiety in American culture. They are not the only commercials in Double Take: in a relishable teaser ad, Hitchcock welcomes us into his library to announce his forthcoming feature The Birds. But in his TV appearances the maestro also constantly advertises himself, projecting himself as his own trademark – at one point, casting his shadow on to his logo, the curly flourish that outlines his stylised silhouette. Remarkably, Hitchcock’s clownishness did not undermine his reputation as a dark psychologist and scare-master: this homeopathic dose of comic syrup only reinforced his authority. So too with Khrushchev: the more jovially he goofed around, the more he petrified America.

Assembled by Grimonprez, Hitchcock’s TV japes reveal a startling preoccupation with doubling, with mistaken or lost identity – themes that recur obsessively in his films. One programme is introduced by the director disguised both as his own apocryphal brother and as the Hitchcock marionette whose string he pulls. Elsewhere he is quizzed by police, and protests, “Wait a minute, sir, you’ve got The Wrong Man.” Conversely, in another sketch, he is assumed to be mad because he insists he is Hitchcock: “Sure, sure, everybody is!” says the orderly who leads him away.

Meanwhile, history is a twin to Hitchcockian cinema: the Cold War was an extended suspense narrative, the Cuban missile crisis its nail-biting peak. Grimonprez’s film confirms the classic theory that cinema – and Hollywood in particular, articulating American anxieties – is most eloquent about history when treating it indirectly as metaphor, as in 1950s space-invasion movies, or indeed 1963’s The Birds. When Hitchcock addressed the Cold War directly – notably in the largely forgotten Topaz (1969) – the results were nowhere near as resonant.

Double Take bounces along wittily in its montage sections, its retro flipness recalling the 1982 archive assemblage The Atomic Café, about H-bomb panic. A knowingly portentous counterpoint is the interwoven story in which Hitchcock (voiced by impersonator Mark Perry) narrates a 1962 encounter with his own future self. An uncanny doppelgänger tale in the Hoffmann/Dostoevsky tradition, it is adapted by British novelist Tom McCarthy from a story by Jorge Luis Borges (another Hitchcock ‘twin’: both men were born in August 1899). This sequence is illustrated with newly shot footage, including images of bowler hats that ‘twin’ Hitchcock with another fastidiously decorous cultural subversive, René Magritte.

Meanwhile, the late Ron Burrage talks about his own career as a Hitchcock lookalike, and relishes the absurdity of making a living as someone else. The presence of the engaging Burrage – whose only real resemblance lies in his girth and his sense of fun – highlights the fact that Hitchcock was his own best and most merciless impersonator.

It is only in the Borges/McCarthy story that Double Take contains anything approaching an explicit commentary. No doubt Baudrillard, Virilio and Zizek are among the virtual presences in attendance, but the film’s theoretical content is to be gleaned largely from its suggestive juxtapositions and repetitions. Edited by Dieter Diependaele and Tyler Hubby, Double Take is a virtuoso feat of collage, only occasionally doctoring its images for effect: at moments, footage of Hitchcock is scrutinised by being slowed down and magnified, the effect recalling both Douglas Gordon’s gallery piece 24 Hour Psycho and Godard’s Histoire(s) du Cinéma.

The film ends with an excerpt of Donald Rumsfeld’s notoriously gnomic speech about “known knowns”, “known unknowns” and “unknown unknowns”. A macguffin, presumably, is a “known unknown”: while no one in a story knows exactly what it is, everyone operates under the assumption that it exists. What could be more macguffinesque than Saddam’s elusive ‘Weapons of Mass Destruction’? In interviews, Grimonprez has talked about ‘lookalike politics’ – which I take to mean a style of politics generated by rhetorical supposition, for example the prosecution of the Iraq war as if the WMD threat were indisputable. The orderly who leads the real/fake Hitchcock to a padded cell tells him that, sure, sure, everyone is Hitchcock. He has a point. Hitchcock’s narratives educated the world in the art of paranoid reasoning; whether watching movies or TV news, we are now so thoroughly schooled in suspicion that, to a modest degree, we are all a little bit Hitchcock. However, that the Iraq war was allowed to happen suggests perhaps that when it came to the crunch, the world was not quite suspicious – not quite Hitchcockian – enough.

Johan Grimonprez discusses making ‘Double Agent’ on page 49 of the April 2010 issue of Sight & Sound

Grey zone: Mark Fisher on Chris Petit’s essay documentary Content (April 2010)

We have always recycled: Rick Prelinger on the incurable rise of ‘archive fever’ (online, March 2010)

The Beaches of Agnès reviewed by Jonathan Romney (Film of the Month, October 2009)

Direct action hero: Tim Lucas on French documentarian Chris Marker (DVDs, June 2008)

Under the influence: Robin Buss on French film-makers’ affinity for Aldred Hitchcock (May 2006)

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934) reviewed by Jonathan Coe (September 1999)