Polls and surveys

Forgotten pleasures of the multiplex, pt 2:

Films E-J

Herbert Ross’s Footloose (1984)

Unloved, unlauded but no longer alone: 80 mainstream movies from the past 30 years that were either commercially or critically buried

« Introduction | « Entries A-D |

Entries K-R » | Entries S-Y »

The Entity

Sidney J. Furie, US, 1981

By Michael Atkinson, critic, US

There may not be, outside of David Cronenberg’s wonder cabinet, a more nitro-powered horror-movie metaphor hell than that fueling this post-Exorcist remnant, in which Barbara Hershey plays an ordinary working-class woman (supposedly based on a real person) who is repeatedly attacked and raped by a huge, invisible being. Aurally and visually calibrated like a taser, Sidney J. Furie’s movie doubles down on the genre grittiness, then wallops you with unrelenting trauma; the bizarre prosthetic effects, of Hershey’s body being manhandled and screwed by unseen hands and body parts, would be merely one of the most lashingly surrealist visions in American film if it weren’t also deeply upsetting on so many levels that it’s like the movie is writing its own library of fiery feminist theory. The anxiety the film produces was too hot to handle, and after years of delays it was dumped, only to be semi-rediscovered by Austrian experimentalist Peter Tscherkassky in 1999 and re-edited as his short ‘Outer Space’. It remains unnerving and savage, arguably the most eloquent movie ever made in Hollywood about the struggle of the sexual underclass.

L’Eté meurtrier

Jean Becker, France, 1983

By Geoff Andrew, head of film programme, BFI Southbank

Released at a time when many were dazzled by the then fashionable cinéma du look (The Moon in the Gutter was made the same year), this subtle yet seemingly more conventional crime movie by the son of Jacques Becker has endured rather better than much of the output of Beineix, Besson et al. The film depends primarily on its sturdy script, which shifts with surprisingly smooth ease from what at first looks like a perky comedy of sexual mores (newly arrived coquette Isabelle Adjani ignites male lust and female gossip in a Provençal village) to an altogether darker, more complex study of treachery, falsehood, obsession and revenge. As events are related from different perspectives, expectations are confounded, stereotypes stripped away to reveal credibly conflicted individuals, and motivations properly muddied rather than simply explained away. Like the Georges Delerue score, the cast – which includes such stalwarts as François Cluzet, Edith Scob, Michel Galabru and Suzanne Flon – is an index of the overall classy craftsmanship, but in Adjani’s remarkable performance, at once forcefully raw yet technically refined, the film explores depths as unsettling as they are revealing.

Excalibur

John Boorman, US, 1981

By Kieron Corless, Sight & Sound

A student ghetto in Leeds, the early 1980s. A dedicated economy of pleasure prevails, its currencies being bodily fluids, copious alcohol and drugs, and recently discovered VHS tapes. Films are viewed communally, in the stygian gloom of dimly lit front rooms in various heightened states. There was a much simpler accounting of a film’s worth back then: in the words of one of my long-lost compadres, either “fackin’ superb” or “fackin’ shit”. In the former category was Boorman’s Excalibur. I can’t remember much about the film itself, more the sensation of stupefied surrender, an almost mystical communion not dissimilar, perhaps, to the film’s own rapturous immersion in a mythical, pre-rational universe. I’ve an abiding impression of thunderous Wagnerian overload, interspersed with quieter moments; an emerald-green world charged with potent poetry and primitive magic; the conviction and intensity of Nicol Williamson as Merlin. It registered as profoundly erotic too. Has Helen Mirren ever been hotter than she is here, playing the evil Morgana? And there’s a sex scene where Arthur shags his wife on a table while still wearing his armour (you won’t find that in Bresson’s Lancelot du Lac). I never saw Excalibur on the big screen, but still, at times it felt like you were actually in the film, as if the distance between viewer and film had been obliterated, so you became, as Jeff Koons once said, “a little lost in the fantasy”. Today, I still couldn’t tell you whether Excalibur is any good or not. It’s possibly kitsch, portentous 1980s nonsense, but I prefer not to watch it again, particularly now I’m permanently sober, and sully the few memories that remain of it.

The Falcon and the Snowman

John Schlesinger, US, 1985

By Maria Delgado, academic and critic, UK

Whenever I see the phrase “adapted from a true story” in the opening credits for a film, I expect a worthy, earnest product boasting ‘fidelity’ to its source material. Here Schlesinger opts for something different. There’s a murkiness of both mood and character motives, as Steven Zaillian’s screenplay melds espionage thriller with slacker movie, all drawn from Robert Lindsey’s investigative study of two homegrown all-American spies nurtured in the bosom of respectable, bourgeois society. These childhood friends, who conspire to sell CIA secrets to the Russians, function as a portrait of the dismembered American psyche in the aftermath of the Vietnam War. Timothy Hutton is the ‘good’ Catholic boy disillusioned by the culture of underhand surveillance to which he is privy; Sean Penn is his loose-lipped, fallacious co-conspirator. The latter is superb as the jerky dealer-cum-addict spiralling out of all control as the pressures pile up. Volatile and vulnerable, his characterisation of the hapless Lee announces the manic energy and technical precision that has marked all his subsequent performances, from the shady lawyer in Carlito’s Way to the crusading activist in Milk.

Femme Fatale

Brian De Palma, France, 2002

By Sam Dunn, head of DVD, BFI

After a devastating performance at the US box office, Femme Fatale limped its way into the UK marketplace as a straight-to-DVD title with little fanfare and barely a murmur from critics. It was followed by the longest period of inactivity in De Palma’s career, a four-year silence only broken when The Black Dahlia and Redacted were offered up in surprisingly quick succession. Packed with all of the classic themes and concerns that made such earlier works as Sisters, Obsession and Blow Out so great (mistaken identity, artifice, doubling, voyeurism etc), Femme Fatale is both a kind of greatest hits package, delivered in bravura style, and a truly entertaining and stylish experience that goes as far as any of De Palma’s most celebrated films in deconstructing the nature of cinema and exploring the relationship between truth and representation. To call this manipulative picture puzzle the last great film of De Palma’s extraordinary career is a no-brainer, but to say that it’s among his finest works is probably closer to the truth.

Final Destination 3

James Wong, US, 2006

By Nick Pinkerton, critic, US

Part three was my point of entry to this very original horror franchise, but any of the other instalments would do. Bringing ankle-high expectations to the multiplex, I saw Final Destination 3 with a loud crowd in downtown Brooklyn and was smitten with the concept’s ingenuity. Not taking kindly to feeling cheated, Death picks off the survivors of freak accidents one by one. In this episode, the carnage occurs on a derailed, no-brakes rollercoaster – the other films concern escapees from an airliner explosion, a freeway pile-up and a speedway disaster, each graphically hallucinated before a (temporary) precognitive deliverance. Death, as it happens, has a terrific sense of humour, and goes about evening the score by setting in motion intricate chains of everyday happenstance that end in spectacularly violent kills – mousetraps built better with each passing sequel. “Fuck death!” shouts a defiant jock here, moments before a weight machine pulps his head. This may seem puerile, but it’s a flicker of originality in a genre increasingly dedicated to cannibalising its past, and it disquiets the spectator in a new way, for more of us honestly suspect that we’ll die in some ridiculous, left-field and embarrassing Act of God rather than at the hands of a nutter with a mask.

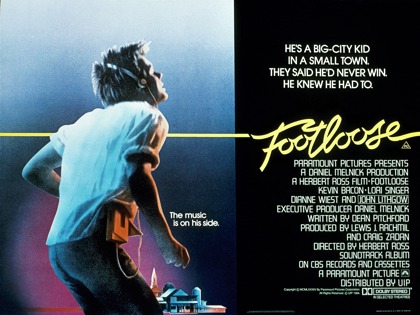

Footloose

Herbert Ross, US, 1984

By Jane Lamacraft, critic, UK

Kevin Bacon plays Ren MacCormack, a city teen who relocates from Chicago to the Midwest sticks, where he finds that rock music and dancing have been banned by John Lithgow’s Bible-thumper. Lori Singer (who beat Madonna to the role) struts her stuff as Lithgow’s daughter Ariel, a sassy missy so keen to kick the small-town dust off her red cowboy boots that, as her friend Rusty (Sarah Jessica Parker) says, she “probably memorises bus schedules”. A battle to stage a prom ensues, and for once the Hollywood diktat – that down-home values always vanquish city-slicking ways – is turned on its head. It has you from the get-go: the opening sequence is a toe-tapping montage of variously attired pairs of feet dancing to Kenny Loggins’s title track. Nearly three decades on, Bacon’s vest-clad set-piece dance in a flour mill looks cheesily 1980s, but the rest of Ross’s drama wears its age well, real song-and-dance joy for the pre-Glee generation. Watch it now, before the remake (with Dennis Quaid in the Lithgow role) hits your screens.

Galaxy Quest

Dean Parisot, US, 1999

By Ben Walters, critic, UK

It’s no easy feat for a film to simultaneously spoof a genre and deliver the goods on its own terms. The Scream franchise, inaugurated in 1996, stands out on this front, but Galaxy Quest deserves as much praise. Tim Allen, Sigourney Weaver, Tony Shalhoub and Alan Rickman play veterans of a Star Trek-style television show, nursing their variously bruised egos on the fanboy circuit before being sucked into space by credulous aliens who mistake them for their last, best hope. The joke is that they turn out to be just that. The cast is superb, deftly negotiating the turn from has-been testiness to self-surprising heroism, and the script, by David Howard and Robert Gordon, is clever and knowing but also copper-bottomed and heartfelt. The real achievement is the film’s treatment of fandom, clear-eyed about its absurdities but unrepentant in celebrating the passion and even romanticism beneath the nerdiness.

The Godfather Part III

Francis Ford Coppola, US, 1990

By Armond White, New York Post, US

It is a great injustice that critics deny The Godfather Part III (1990) any of the effusive acclaim given The Godfather (1972) and The Godfather Part II (1974) – this mistake overlooks the great power of Part III as Coppola complicated and fulfilled his project. Coppola elevated the gangster movie by importing art-movie strategies into the time-folding structure of Part II, then in Part III he added self-referential details and casting that certifies the autobiographical ethnic immigrant legacy. The object of Part III is to personalise a Hollywood genre that had become the folly of superficial movie-brat appreciation. Michael becomes American cinema’s greatest character since Scarlett O’Hara by embodying the 20th-century dilemma of upholding American identity while being conscious of the country’s contradictory, sometimes immoral acts; his punishment and long-delayed confession reunites the Godfather saga with a Catholic sense of sin and provides the series (and Al Pacino’s stages-of-man performance) with well-proportioned unity. Despite a few flawed sequences and performances (though not Sofia Coppola’s cosseted Mary, an uncannily contemporary product of the depravity Don Vito began) violence is shown to exact its cost. The narrative thrust of the first two films require this – they are incomplete without it. Part III matters because Michael, the corrupted American scion, finally repents. Unfortunately, repentance – the emotion that gave Greek tragedy its power – is what The Sopranos era has eliminated.

Gojo reisenki: Gojoe

Ishii Sogo, Japan, 2000

By Anton Bitel, academic and critic, UK

Gojoe might formally resemble a chanbara (period swashbuckler), but it deviates from generic convention no less than its main characters – repentant warrior monk Benkei (Ryu Daisuke) and Genji clan heir Yoshitsune (Asano Tadanobu) – abandon worldly affairs. Disguised as a demon, Yoshitsune slices through armies of Heike samurai with preternatural calm, while Benkei hopes to expiate his own bloody past by ending the slaughter. Both men are on a quest for enlightenment, the one trying to overcome personal demons, the other to become a god, and their ultimate, pre-destined confrontation on Kyoto's Gojoe Bridge spans the divide between history and fiction, politics and metaphysics, chaos and cosmos. Ishii presents a revisionist version of this legendary clash, before finally reattaching his idiosyncratic re-imagining to the inherited tradition – but by then his characters have transcended their own myth, even their own humanity, and evaporated into a plane of pure spirit. The combination of deadly serious performances, unnervingly eerie locations, restlessly fluid camerawork and the ominous rumblings of an industrial score ensures that Gojoe bristles with unrelenting intensity.

Grégoire Moulin contre l’humanité

Artus de Penguern, France, 2001

By Philip Kemp, critic, UK

Artus de Penguern is best known as an actor – he played the blocked writer Hipolito in Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s Amélie (2001) – but he also directs, and his first and only feature could be conceived as the anti-Amélie. Both films share a heightened, stylised vision of Paris but where in Jeunet’s saccharine whimsy everybody can be redeemed by the power of sweetness and innocence, de Penguern’s city of dreadful night is peopled by crazed monomaniacs whose vindictive fury can be stilled only by violent death. The film’s view of humanity is relentlessly and hilariously bleak. Relations between the sexes are a disaster area; almost everyone has been maltreated, cheated on or dumped, and the nearest to a harmonious couple are a pair of predatory sex maniacs. Almost everybody teeters on the edge of homicidal violence; the only sane people Grégoire (de Penguern himself) encounters in his nightmare odyssey are some mild-mannered porters from the Rungis meat market, and inevitably it’s them he attacks when he finally snaps. Grégoire Moulin mines a vein of gleefully misanthropic comedy rarely seen on screen since the heyday of W.C. Fields.

Hangin’ with the Homeboys

Joseph B. Vasquez, US, 1991

By Michael Brooke, critic, UK

This smart, funny, wordly-wise portrait of four young men of assorted ethnic heritage opened too close to the hype-magnet Boyz N the Hood to have a chance of striking out on its own. Despite good reviews it was deemed too similar and tanked at the box office. But, as Karen Alexander pointed out in S&S (December 1991), it’s an almost vanishingly rare example of early 90s New Black Cinema that offers an intelligently critical study of its protagonists’ masculinity instead of excusing and/or celebrating its excesses. Johnny has academic ambitions, Vinny – aka ‘Fernando’ – mimics Dennis Christopher in the similarly charming Breaking Away (1979) by pretending to be Italian, Tom has dreams of acting stardom, while Willie’s favourite catchphrase anticipates (and may have been ripped off by) Ali G a decade later as he responds to every self-inflicted setback with a knee-jerk: “It’s because I’m black, right?” Some of the plotting is clunky (Johnny’s romantic dreams are shattered by a wildly implausible coincidence) and the female characters needed far more rounding for the underlying message to hit home, but it’s an infinitely better and indeed more genuinely charming film than its title suggests.

Henry V

Kenneth Branagh, UK, 1989

By Graham Fuller, critic, US

I first saw Kenneth Branagh’s sombre directorial debut in the Cannes market, where presumably it was shunted because of the French Revolution bicentenary. Despite the allegations of hubris then levelled at its maker, the film seemed revelatory as a post-Falklands War denunciation of imperialist warmongering. Many viewings since have reinforced my opinion that it’s one of the finest of all Shakespeare movies, up there with Dieterle and Reinhardt’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Welles’s Othello and Chimes at Midnight, Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood, Kozintsev’s King Lear and Olivier’s own Henry. Branagh’s bold imports from the Henry IV plays, showing the significance of Falstaff for Prince Hal and the Boar’s Head crew, mesh perfectly with Henry’s monarchical isolation on the night before Agincourt, as does Bardolph’s hanging, which Olivier, minding British wartime morale, omitted along with the Scroop conspiracy. In keeping the latter episode, Branagh laid bare the exigencies of medieval realpolitik. Stylistically, the film constantly astonishes – the subtle tracking shot that follows Branagh’s spine-tingling Saint Crispin’s Day speech and the bravura 500-foot track across the Agincourt carnage betokened similar sequences in The Lord of the Rings and Atonement.

Hudson Hawk

Michael Lehmann, US, 1991

By Naman Ramachandran, critic, UK

This box-office turkey ($65 million budget, $17 million takings), universally reviled by critics and shunned by audiences, deserves a re-evaluation. Upon repeat viewing, it is difficult to see why the film was so disliked. Bruce Willis, the charismatic lead, was at the height of his popularity having just come off Die Hard 2. The plot, by Willis and Robert Kraft, about a brother-sister pair attempting world domination by controlling Da Vinci’s gold-making machine, is enjoyably hokey but certainly no more outlandish than, say, Raiders of the Lost Ark. The dialogue (Steven E. de Souza and Daniel Waters) bristles with anarchic one-liners. Marx Brothers purists will shudder, but the film is so full of wisecracks that it requires a second viewing to appreciate them all, like Duck Soup. And the sharply edited sight gags are evocative of Buster Keaton in his pomp. Plus, as the Mayflower siblings, Sandra Bernhard and Richard E. Grant are among the best comic villains ever. And any film containing the immortal line: “If Da Vinci was alive today, he’d be eating microwave sushi, naked, in the back of a Cadillac with the both of us,” can’t be bad, as the legions who have made the film a DVD hit will testify.

The Hunger

Tony Scott, UK, 1983

By Carmen Gray, critic, UK

The Hunger brilliantly marries the classic vampire genre with the fashion-savvy energy of a then-new MTV age. It opens with a live nightclub performance of ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead’ from seminal goth rock band Bauhaus, the singer posturing bat-like behind an iron grid in shadow and blue light as a coldly glamorous Catherine Deneuve smokes and looks on from behind her sunglasses. Critics disparaged the film on its release as all slick, flashy style – but therein lies its very charm.

David Bowie channels his lean, androgynous elegance and otherworldly stage image into the role of John Blaylock. Picked up in 18th-century Europe by Deneuve’s Miriam, a vampire from ancient Egypt, he’s one of a line of her lovers who last 200 years before degenerating into sentient dust – and his time’s agonisingly up. Why Miriam is exempt from this fate is never explained, but plot details seem insignificant amid the dream vampire-couple pairing of Bowie and Deneuve and their sumptuous Manhattan townhouse of antiques and endlessly billowing curtains.

Deneuve’s scorching chemistry with Susan Sarandon (as a doctor tempted into vampirism) is also key, with much controversy surrounding the film centred on their sex scene. But The Hunger’s unabashed eroticism sits naturally with a genre always closely tied to the sensual, turning as it does on the paradox of creatures voraciously parasitic and fatally addicted to perpetuating life.

Hustle & Flow

Craig Brewer, US, 2005

By Trevor Johnston, critic, UK

The story of a Memphis pimp who fancies himself as a hip-hop artist seems made for the ersatz redemption Hollywood thrusts upon us on a regular basis. Not in the hands of writer-director Craig Brewer, however, who treats his film’s characters and circumstances with unfailing respect, who clearly knows the terrain (Memphis is his home town) and who gets a magnificent performance from stalwart supporting actor Terrence Howard, who absolutely nails the central role. His Djay is a canny operator, adept at keeping his working girls in line, but then discovers another side of himself while putting together a demo tape to press into the palm of Ludacris’s local-boy-made-good when the rap star passes through his old stomping ground on the Fourth of July. While that make-or-break confrontation is taut as cheese wire, the landmark sequence here is when Howard and cohorts lay down their tracks in a jerry-rigged home studio, the act of conjuring music from silence proving so unexpectedly primal it gives them a life-changing sense of self-worth. In this inspirational yet far from saccharine moment, Brewer reveals his true agenda, a potent statement of the human potential going to waste in divided America’s forgotten inner-city streets.

The Icicle Thief

Maurizio Nichetti, Italy, 1989

By Guido Bonsaver, academic and critic, UK

This is a film that should appear in every anthology of postmodernist cinema. It marks the peak of Maurizio Nichetti’s film genius: he co-wrote the script, directed the film and played two different characters. It tells the story of a film director who shoots a remake of De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, then watches as its television screening is totally messed up by a Berlusconian-type commercial channel that continuously interrupts the black-and-white film with colourful adverts. The director tries to intervene but, in the process, causes a surreal fusion of three different levels of reality – the neorealist remake, the adverts and the director’s life – with the funniest of consequences. But The Icicle Thief is not just a successful comedy of errors; it contains a heartfelt homage to neorealist cinema and conveys a serious point about the damage to film culture and to Italian society inflicted by the increasing power of commercial television.

I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead

Mike Hodges, UK/USA, 2003

By James Mottram, critic, UK

Unlike its predecessor Croupier, there was to be no reprieve for Mike Hodges’ richly atmospheric I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead, no second life courtesy of US critical support. A former London gangster out to avenge the death of his brother, this ambiguous character study was inevitably dismissed as a rehash of Hodges’ 1971 debut Get Carter. But Clive Owen’s inscrutable hardman Will Graham couldn’t be more different from Michael Caine’s Jack Carter, having spent the last three years living off the grid, running from his old self. “It’s grief,” he says, “for a life wasted.”That the “non-consensual buggery” of Graham’s younger sibling Davey, an act that causes him to take his own life, is so central is a fabulous face-slap to the macho posturing of a genre that had, post Guy Ritchie, lapsed into self-parody. Even in the wake of Tony Soprano’s therapy sessions, the scene in which Graham listens to a counsellor explain the psychological implications behind Davey’s rape is wonderfully unexpected. Epitomised by Ken Stott’s kingpin, the male characters all feel threatened, their sexuality, status and even sanity all under attack. In a world that stinks of new money, Hodges’ nocturnal noir is a lament for a bygone era, one that Jack Carter knew so well.

Impulse

Graham Baker, US, 1984

By Adrian Martin, academic and critic, Australia

The specialty of British-born director Graham Baker (Omen III: The Final Conflict, Alien Nation) is the subtle exaggeration of disquieting incongruities in the daily world. The storyline of Impulse gives him the perfect premise. One day, for no apparent reason, ordinary people start acting out of impulse, shedding all forms of civilised restraint. In most movies this would lead to grand dramatic gestures: utopia or apocalypse. Impulse refuses these options. Neither divine nor evil, Baker’s characters stay close to the banal everyday. Although a little sexual licence flowers in dark doorways around town, the impulse these ordinary folk indulge in is acting out peeved, spiteful fantasies – the kind of aggression that arises from life’s 1001 daily, niggling irritations. After the revolution, what happens in Impulse is that a typically harried bank customer is now willing to shoot the people in front of him to get ahead in the teller’s queue; or a little old granny, sick of waiting for the traffic light to change, will gleefully ram her car into it.

Isn’t She Great

Andrew Bergman, US, 2000

By Ryan Gilbey, New Statesman, UK

One scene embodies the unsung sassiness of this razzle-dazzle, no-warts-at-all biopic of Jacqueline Susann, author of high-trash bestseller Valley of the Dolls. Before she hits the big time, Susann is moping in the street after another rejection. When, she wonders, will her luck change? “I’m 29 years old,” she sighs. “Yeah, right,” scoffs a passing businessman. “Fuck you!” she responds – the joke being that Bette Midler, who plays Susann, was 52 at the time. In other words, this is a biopic that knows it’s a biopic. Even the elisions (the near-exclusion of Susann’s autistic son, the prettified account of her death from cancer) comment on the whole genre’s compromised nature. The movie is infectiously upbeat but never twee: the garish colours tickle our eyeballs and Paul Rudnick’s script has champagne bubbles in every other line. The showbizzy cast is a knockout: Midler, Stockard Channing, David Hyde Pierce, John Cleese, Amanda Peet and the incomparable Nathan Lane, an icon of the overlooked if ever there was one.

Jennifer’s Body

Karyn Kusama, US, 2009

By Hannah McGill, critic, UK

The simultaneous hype and opprobrium dealt out to star Megan Fox and writer Diablo Cody – as geek-combusting megababe and hipster queen respectively – rather swamped this film upon release. And with Hollywood groaning with come-of-age kids whose lives were changed by Heathers or Election or Mean Girls, a degree of fatigue now attends every perky parody of carnivorous high-school mores. So, why favour this one? Because throw out all the packaging it came in, and it’s surprisingly eloquent about the pain of adolescence and the contradictions associated with female power. The near-erotic intensity of teenage female friendships; the death cult that reliably possesses sensitive boys and girls at a particular age; the can’t-win teen-girl conundrum of being equally derided for innocence and experience… Jennifer’s Body captures all of this with an eloquence that almost feels misplaced within its trashy trappings. Sure, it’s got its silly bits and its horror effects and school slang will date as rapidly as these things do, but unlike Cody’s far more celebrated Juno – from which feelings were brutally excised to make way for witticisms – it’s frank, funny and empathetic about female identity-forming and the ravages of hormonal change.

Joan Lui – Ma un giorno nel paese arrivo io di lunedì

Adriano Celentano, Italy, 1985

By the Ferroni Brigade, Austria and Germany

Who would make a film like this today? It’s a monumental, monstrously expensive, madly inventive experimental musical about the Second Coming of a Christ who arrives into a world of violence, corruption and hypocrisy that looks strikingly like modern Italy, whose apostles are left-wingers of all kinds, and who’ll sing ’n’ dance it out with evil incarnate to save mankind from a fate it likely deserves. Only during the 1980s, that decade of decent mass enlightainment, could you pull one like this – and only if you were the last real European star, a pop-cultural axiom, a one-man industry/genre. Joan Lui was a financial fiasco of singular proportions and critics were always too bland-brained to appreciate Celentano’s flamboyant genius. Today, one watches the film and weeps for all that lost greatness and kindness.

See also

Sight & Sound’s collected film polls and surveys

Galaxy Quest reviewed by Kim Newman (May 2008)

Isn’t She Great reviewed by Charles Taylor (August 2000)

I’ll Sleep When I'm Dead reviewed by Ryan Gilbey (May 2004)