Polls and surveys

Forgotten pleasures of the multiplex, pt 1:

Films A-D

Robert Aldrich’s All the Marbles (1981)

Unloved, unlauded but no longer alone: 80 mainstream movies from the past 30 years that were either commercially or critically buried

« Introduction |

Entries E-J » | Entries K-R » | Entries S-Y »

After Dark, My Sweet

James Foley, US, 1990

By Jason Wood, programmer, UK

Pulp novelist Jim Thompson has been adapted for the screen several times with the transition never entirely successful (The Grifters comes closest). And yet, from the controversy that dogged Michael Winterbottom’s The Killer Inside Me through to Maggie Greenwald’s feminist tilt at The Kill-Off and Bertrand Tavernier’s relocation of Pop. 1280 to a French African colony in Coup de Torchon, Thompson on screen has always caused a ripple. But James Foley’s 1990 adaptation of After Dark, My Sweet, set in the simmering heat of a rundown suburb of Palm Springs, seems to have evaded the radar. Given that this is the tale of an apparently dim-witted ex-boxer (Jason Patric) on the run from a mental institution who falls into the clutches of the vampish Fay (Rachel Ward), the staple Thompson themes of paranoia, treachery, violence, mental instability and sexual tension are all accounted for. Foley charts an intimate and at times poetic journey towards failure and misery following the incompetent kidnapping of a child. Replicating the moral ambiguity inherent in the novel, this is a taut, intelligent work, powered by a suitably venal turn from Bruce Dern as the unscrupulous Uncle Bud.

A.I. Artificial Intelligence

Steven Spielberg, US, 2001

By Jonathan Rosenbaum, critic, US

I’m not alone in considering A.I. Artificial Intelligence a very great and deeply misunderstood film. Others as disparate as Andrew Sarris and the late Stan Brakhage have more or less agreed with me, as well as my friend and favourite academic critic, James Naremore. But it’s also clear to me that any ordinary auteurist way of processing cinema can’t begin to handle this masterwork adequately. Reading it simply as a Spielberg film, as most detractors do, or even trying to read it simply as a Kubrick film, is a futile exercise with limited rewards, even though the fingerprints of both directors are all over it. (I tend to see it as I believe Kubrick sometimes envisioned it – as a film of his, informed by Spielberg’s sensibility.) Seeing A.I. as a perpetually unresolved dialectic between these filmmakers yields a complicated logic, an ambiguity where the bleakest pessimism and the most ecstatic feelgood enchantment swiftly alternate and even occasionally merge – viewed this way, it becomes a far more enriching experience, however troubling and unresolved. As a profound meditation on the difference between human and mechanical, it also constitutes one of the best allegories about cinema.

Alien 3

David Fincher, US, 1992

By Jason Wood, programmer, UK

The most reviled entry in the Alien series and a relative box-office failure, Alien 3 was Fincher’s feature debut. Concocted by a small army of writers, Walter Hill and Vincent Ward among them, the film is oppressive enough to feel like Kafka in space. Sigourney Weaver returns as Ellen Ripley and finds herself on a desolate penal colony populated by rapists. If Ripley’s gender were not enough to cause disharmony, her parasitic stowaway really puts the fiend among the felons. Since the film was shot in the UK, this dissolute bunch are portrayed by such British stalwarts as Pete Postlethwaite, Paul McGann and Ralph Brown. None of this sounds promising, but Fincher’s film has much in common with Ridley Scott’s original: the build-up is slow, accruing tension by increments, and there’s a palpable sense of dread. Not until some way in does a prisoner yell, “It’s starting’”as the special effects are wheeled out and the film spins off the rails. But until then it is gloom all the way and all the better for it.

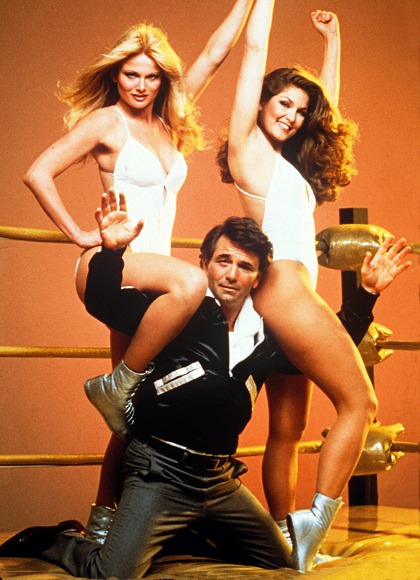

All the Marbles

Robert Aldrich, US, 1981

By Nicolas Rapold, critic, US

This story of a female wrestling duo and their hustling trainer (Peter Falk!) is forgotten even by Aldrich fans, who tend to tune out after Hustle (1975), but as the trio tool around the grapplers’ circuit in a Detroit clunker – set against fading Rust Belt landscapes – their grit and hope come through. Performers playing at a seemingly fake sport but with very real stakes of bruises and cash, the ‘Dolls’ (Vicki Frederick and Laurene Landon) cling to their showbiz dignity even while covered in mud. Aldrich’s nose for the pleasures of violence (specifically, catfights) remains keen in the terrifically entertaining bouts, some starring professional wrestlers. Aldrich died two years later, but nailing the climactic fight in front of a sing-along audience at the MGM Grand, he went out with a bang.

The Arrival

David N. Twohy, US, 1996

By Nick Bradshaw, Sight & Sound

This back-of-the-truck paranoiac sci-fi B movie – in which Charlie Sheen’s rogue ex-NASA scientist discovers hot-planet-loving aliens in human guise ramping up CO2 production from covert jungle power stations across Latin America – is not only the most entertaining screen treatment of global warming I’ve seen, but the most compelling allegory for the perverse bind in which our climate change politics are now stuck. A sequel today would have to feature an alien takeover of the US Republican party – which brings to mind The Arrival’s spiritual antecedent and the original biomorphic takeover fable, Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1955). Like Don Siegel’s cult classic (and unlike Roland Emmerich’s impatient planet-buster The Day After Tomorrow, 2004), The Arrival puts its hysteria on slow burn: it has its showy special effects, but its most severe implications are delivered in some wonderfully reticent dialogue by a smooth Ron Silver. I can’t say the film has Body Snatchers’s pulp poetry, but it does feature attempted murder by bathtub and a goateed Sheen at the nadir of his popularity taking every opportunity to expose a pumped and oiled torso.

Avalon

Oshii Mamoru, Japan, 2000

By Jasper Sharp, critic, UK

Overshadowed by Oshii’s anime pair Ghost in the Shell (1995) and Innocence (2004), this Tarkovsky-inspired foray into live action possesses a similar pessimistic regard for technology. Filmed in Poland, with Polish actors performing in their own language, the film depicts a group of virtual-war-game addicts and their quest for their in-game Holy Grail. Oshii’s idiosyncratic use of CGI follows a different tack from other titles of its ilk, its dystopian ‘reality’ scenes digitally leached of colour, which only returns to the frame to varying degrees the further its characters are from the coldly inhuman technology of Avalon’s false paradise. The rendition of the immersive game world is stunning: tanks roll across open plains as the players hide out in ruined buildings, assailed by helicopters and heavy-duty artillery fire; when hit, bodies flatten into two-dimensional projections before shattering into a myriad of triangular shards. In the end, our protagonist’s elevation into the final ‘Class Real’ phase of the game, accompanied by Kawai Kenji’s characteristically majestic operatic score, really does take the film to another level entirely.

Boogie Boy

Craig Hamann, US, 1997

By Michael Brooke, critic, UK

Ex-con Jesse (Mark Dacascos) tries to make it as a rock drummer while under constant threat of being sucked back into a life of drug-fuelled crime. It’s hardly an original premise, and writer-director Hamann’s previous claim to fame as one of Quentin Tarantino’s buddies back in his Video Archives period (mutual friend Roger Avary is executive producer here) didn’t set pulses racing in anticipation. But the director turned out to have a real feel for scuzzy low-life dialogue, fleshed out here by a surprisingly upmarket cast that includes Frederic Forrest and Emily Lloyd as the weirdest motel habitués since Norman Bates. There’s a barnstorming turn from Unforgiven’s Jaimz Woolvett as Jesse’s heroin-addicted former cellmate, and cameos by the super-culty likes of Joan Jett, Traci Lords and Linnea Quigley. As the troubled Jesse himself, Mark Dacascos reveals a wider thespian range than his martial-arts past might have indicated, though a bone is tossed to his fanbase in the form of a furious fight at the climax. Despite this promising start, Hamann’s filmography has since run dry.

Bound

Andy Wachowski & Larry Wachowski, US, 1996

By Hannah McGill, critic, UK

Amid the many dark-witted, bloody capers that surfaced in the 1990s, the Wachowski brothers’ pre-The Matrix mob thriller stands out for its simplicity, discipline and style. At once contained (it barely leaves one apartment) and baroque (crazed camera angles, a vividly dramatic score), it balances brilliantly excess and control. Then there’s the innovation that almost prevented it from getting made and that remains startlingly unusual today: a central couple who happen to be gay and whose gayness neither defines nor destroys them. (Persuading two mainstream actresses to take the roles was a challenge for the directors, yet Jennifer Tilly and Gina Gershon have never been better or better cast.) Bound is far from innocent of the ironic, referential sensibility so prevalent at the time of its making: the gruff mobsters, Tilly’s hyper-feminine moll and Gershon’s swaggering tomboy all come from the big box of movie archetypes, and the film’s moral blackness and relentless pacing pay tribute to Hitchcock. Still, Bound feels fresh and sincere, rather than film-school smug, its confidence prefiguring the familiar/original shot in the arm that was The Matrix. Its very straightforwardness is rewarding, coming as it does within a genre that so often births tangled plots and silly twists; its performances and presentation never falter.

The Bounty

Roger Donaldson, UK/US, 1984

By Patrick Fahy, BFI

In the late 1970s, David Lean and Robert Bolt toiled on scripts for a two-film epic about the Bounty mutiny, which (as per Richard Hough’s source book) blamed Fletcher Christian for troublemaking while casting Captain Bligh as hero. Though budgets sank that project, Bolt later rewrote the first script for this, Donaldson’s first Hollywood film, charting the Bounty’s voyage as flashbacks from Bligh’s court martial – thus the film itself puts Bligh on trial (and restores his honour). Mel Gibson proves suitably English and turbulent as Christian, but Anthony Hopkins is magnificent as Bligh, every inch Bolt’s description, “the soul of a hawk in the body of a pigeon”. His navigating from memory across 4,000 miles of ocean provides a stirring climax. Vangelis’s score has dated, but the film has Lean’s fingerprints all over it: beautiful locations, a raft of fine actors (Day-Lewis, Neeson, Olivier etc), Bolt’s signature law-versus-nature theme and a realistic maritime feel, captured by cameraman Arthur Ibbetson (twice Lean’s focus puller, and hired here at Stanley Kubrick’s recommendation when the original DP jumped ship days before shooting).

The Box

Richard Kelly, US, 2009

By Mark Fisher, critic, UK

The Box is based on Richard Matheson’s 1970 short story ‘Button, Button’, later adapted into an episode of the revived The Twilight Zone in 1986. A well-dressed stranger, Mr Steward (a magisterially disquieting Frank Langella), arrives at a family’s home carrying a box with a button on top of it. If they press the button, Steward informs them, they will receive a million dollars; however, someone that they don’t know will die. This metaphysical-moral dilemma becomes the basis of a film that occupies the space between true horror and science fiction and the realm of the weird. Kelly uses elements from both Matheson’s story and the The Twilight Zone, adding references to Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Sartre’s existentialism, conspiracy theories and his own childhood experiences. Sometimes this syncresis can seem unwieldy, but ultimately The Box has the (in)consistency of a dream and the quality of an infernal labyrinth. In part, The Box is disturbing because the nightmare geography it opens up – in which actions in one part of the world result in suffering and death elsewhere – is disconcertingly in tune with the geopolitical predicament that globalised capitalism and eco-catastrophe impose on us.

Breakdown

Jonathan Mostow, US, 1997

By Tim Robey, The Daily Telegraph, UK

Jonathan Mostow has done mid-level studio blockbusters (U-571, Surrogates) and one perfectly solid franchise instalment (Terminator 3), but he’s never improved on Breakdown, a resiliently simple idea pushed into ever sweatier places. It begins with a road trip, an apparent breakdown and a lift from a stranger (J.T. Walsh, at his matter-of-fact best). The reveal is an organised kidnapping ring, which demands far more money than Kurt Russell is able to cough up for his captured wife (Kathleen Quinlan). Mostow’s tight hold on the script’s thumbscrew logic is matched by his skill with the cast: Russell is so good at registering the steps from smug, flustered city rat turning heads in a diner to bewildered terror that you wonder why more Hitchcockian everymen haven’t come his way. There’s a dash of Duel (1971), a hint of The Hitcher (1986) and, like John Dahl’s Joy Ride (2001), it’s a redneck roadkill suspenser that knows exactly how to use the rear-view mirror.

The Butterfly Effect

J. Mackye Gruber & Eric Bress, US 2003

By Mark Fisher, critic, UK

“Change one thing, change everything,” goes the tagline from The Butterfly Effect. The well-known concept derived from chaos theory maintains that small causes can produce massive effects – the famous example being the flutter of a butterfly’s wings in one part of the world causing a storm somewhere else. But while The Butterfly Effect retains the idea that small changes can result in unpredictable consequences, the film – made all the more disturbing because it stars Ashton Kutcher, familiar from such froth as That ’70s Show and Dude, Where’s My Car? – has a more bleakly pessimistic message: you can’t change anything important; misery is inevitable; all you can change is who suffers and what afflicts them, and even that won’t be the result of deliberation. Kutcher plays the multiply traumatised Evan Treborn, who discovers that he has the ability to go back into crucial moments of his past and alter them, as if he is the digital editor of his own life. But he finds that averting one trauma always produces another in its place. In the end, The Butterfly Effect owes more to theologian Alvin Plantinga’s concept of ‘transworld depravity’ – the idea that evil and suffering are inevitable in any conceivable world in which human beings have free will – than to the open-ended ecosystems of chaos theory. Plantinga developed the idea because he wanted to prove that God and suffering were compatible, but The Butterfly Effect gives us the transworld depravity without any possibility of redemption. Here, it is as if the fatalism that simmers not far beneath consumer culture’s obligatory optimism suddenly comes to the fore. And, in the mid-2000s, the film’s notion that sometimes catastrophe is not amenable to intervention could not help but play as – a perhaps appropriately unintentional – comment on misadventures in Iraq.

Une chambre en ville

Jacques Demy, France, 1982

By Geoff Andrew, head of film programme, BFI Southbank

Maybe it was because the score was by Michel Colombier rather than Demy regular Michel Legrand; maybe it was because Deneuve’s insistence on singing the lead role herself led the director to cast Dominique Sanda (who agreed to be dubbed); maybe it was because of the background – a violent 1950s dockers’ strike – to the tale of a doomed adulterous amour fou. Whatever the reason, this dark, deliriously intense liebestod never attained the success of The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964), and has therefore barely travelled beyond France. More’s the pity, since as with the earlier film, once one accepts the formal artifice of an all-sung narrative, the mix of poignant music, a rich libretto, exquisite expressionist design and vivid characterisation steadily builds to a denouement of truly operatic power. Though Sanda and Richard Berry are excellent as the ill-starr’d lovers, they are perhaps upstaged by Danielle Darrieux as the former’s rueful mother and by Michel Piccoli – bilious green suit and red beard evoking psychotic jealousy – as her impotent cuckold husband. A mid-song throat-slitting is merely the most shocking moment in a virtually unknown masterpiece.

Contact

Robert Zemeckis, US, 1997

By Jonathan Romney, The Independent on Sunday, UK

At the time of Contact, Robert Zemeckis said what really excited him about CGI was that it allowed him to change the colour of a sky. Before his increasingly ugly experiments with motion capture (Polar Express etc), Zemeckis was exploring the more delicate possibilities of the new special-effects palette. This drama about the search for extra-terrestrial life ostensibly promises a cosmic blockbuster but proves rather more adult and introspective. Certainly, there’s a New Age/therapeutic streak to this inner-space odyssey, in which Jodie Foster’s scientist ventures into the Great Beyond, only to find… herself. But Zemeckis’s elegant visual imagination makes her voyage remarkably affecting, even when Foster’s Ellie arrives at her destination, which resembles a hippy-era velvet painting. The film has an inspired opening sequence: as we pull back further and further from earth, generations of radio broadcasts hover around the planet. Another image that has stayed with me is a close-up of Foster’s face in transit, its contours uncannily shifting and warping as she hurtles into the unknown (like the missing reverse-angle shot of 2001’s stargate sequence). Few have followed, but Contact suggested a path for CGI genre cinema that was subtly expressionistic, even anti-spectacular.

Contact High

Michael Glawogger, Austria, 2009

By the Ferroni Brigade, Austria and Germany

This wondrous comedy cocktail combines inspirations from such divergent sources as stoner psychedelia, Louis de Funès farces and literary influences from Lewis Carroll to Vonnegut to create a hallucinatory hippy-Buddhist mandala. It’s one of Glawogger’s richest and most personal films, but it’s conceived as the kind of universal popular entertainment that doesn’t care for target-audience tailoring and thus doesn’t fit the marketplace. Hence Contact High failed to make contact with a large audience in Austria and remains unseen almost everywhere else – and ironically now waits be resurrected as one of the magical maudit masterpieces of the past decade.

The Craft

Andrew Fleming, US, 1996

By Sophie Mayer, academic and critic, UK

The far edge of grunge and the pinnacle of The X-Files marked out 1996. Dark magic as a metaphor for teenage disaffection was in fashion: the next year would see the emergence of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Harry Potter, a series of books in no way reminiscent of Jill Murphy’s The Worst Witch, made into a television movie starring Fairuza Balk in 1986. In The Craft Balk plays the worst witch again, but here giggling potions and Grand Wizard crushes are replaced by homoerotic rituals and the crushing of romantic rivals to death. Sarah (Robin Tunney) inherits supernatural powers from her mother; her arrival in town prompts Nancy (Balk), the dark rebel, to call together a coven of disaffected girls. Empowerment is fun at first, punishing jocks and creating beauty to a perfect mid-90s soundtrack of Elastica, Juliana Hatfield and Portishead, plus Siouxsie and The Smiths. Dumb and jumpy enough for a Halloween drinking game, The Craft is – until its disappointingly hysterical conclusion – a smart satire on adolescent fears.

Deep Cover

Bill Duke, US, 1992

By James Bell, Sight & Sound

Bill Duke’s bleak thriller has had its champions, but still hasn’t the reputation it deserves and it’s far too often lumped in with more routine exploitation movies. Here the drug barons aren’t charismatic Scarfaces we secretly root for, they’re ugly and nasty – the repellent Felix Barbosa was never going to inspire a gangsta rap tune as Tony Montana did. It’s a film with a genuinely dangerous edge, in which violence is used to tighten the narrative tension, not to offer show-stopping release. But neither does Deep Cover deploy a contrived ‘grittiness’. It sits in its own distinct place, fascinating in the tension it forges in the marriage of Michael Tolkin and Henry Bean’s superb script – rooted in realism and issues of race, political hypocrisies and personal motivations – and the film’s stylised, visual artifice, poetic narration and brilliantly used hip-hop score. That tension also sparks between Laurence Fishburne and Jeff Goldblum; neither has ever been better, Fishburne coiled with incredible intensity as the conflicted undercover cop, and Goldblum, as the increasingly corrupted attorney, giving the film unpredictable, eccentric dimensions. You can return again and again to Deep Cover and find new notes. It’s one of the most distinctive thrillers of the 1990s.

De l’autre côté du lit

Pascale Pouzadoux, France, 2008

By Ginette Vincendeau, academic and critic, UK

Despite recent assertions in the British press that “France is a romcom-free zone” there has been a remarkable rise in French romantic comedies in the last ten to 15 years. The phenomenon is clearly related to the popularity of the Hollywood genre, but equally its French credentials go back to the New Wave, and more recently Amélie (2001). It is also connected to an equally remarkable rise in women directors. This combination of popular genre, American aura and feminine focus means that – quelle surprise! – such films are non grata for auteur critics. Yet if the 100 or so films in the category are uneven, there is much to treasure. De l’autre côté du lit is one of my favourites. A youngish couple with two children going through a bad patch decide to swap roles – Monsieur will stay home and look after the children, Madame will take his manager’s post in the office. He guffaws that at last he’ll have a rest, but ends up exhausted while she blossoms. It’s funny, stylish, has two of France’s top stars (Sophie Marceau and Dany Boon) and makes a feminist point – which is more than one can say of many French films of higher repute.

The Devil Wears Prada

David Frankel, US, 2006

By Nick James, Sight & Sound

I was the lone male at a screening clearly set up for alumni of women’s magazines when I first saw The Devil Wears Prada. Despite feeling about as welcome as a hairball in a freshly painted room, I had a good time, without feeling I needed to engage too heavily (I didn’t have to write about it). Only now have I noticed, for instance, that David Frankel directed television series like Entourage, Sex in the City and Band of Brothers. Yet the film, adapted brilliantly for the screen by Aline Brosh McKenna from Lauren Weisberger’s novel, stayed with me. Initially, I parked it as a good genre piece that comes pretty close to a classical Hollywood comedy of the Lubitsch-Wilder type without quite getting there. On second viewing, I conceded that it was much sharper than I gave it credit for, particularly about vanity. Of course, I love it partly because it’s about a magazine editor; my fantasy scene is where dragon editor Meryl Streep has lovely assistant Anne Hathaway poised at her shoulder to tell her who every guest is at a party (I could use one of those). And, of course, Hathaway’s stance mirrors my own semi-fascinated, half-hearted, love-disdain for fashion. I have a feeling that this film will get better and better with age.

See also

Sight & Sound’s collected film polls and surveys

A.I. Artificial Intelligence reviewed by Philip Strick (October 2001)