Primary navigation

Tim Lucas finds more than a touch of Tennessee Williams’ southern gothic in two tales of familial decadence

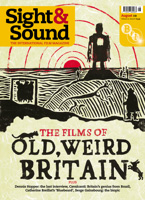

Girly

Freddie Francis; UK 1969; Scorpion Releasing; Aspect Ratio 1.78:1; Features: video interview with screenwriter Brian Comport, audio interview with Freddie Francis, alternative title card, trailers

Goodbye Gemini (pictured)

Alan Gibson; UK 1970; Scorpion Releasing; Aspect Ratio 1.78:1; Features: audio commentary with star Judy Geeson and producer Peter Snell, trailer

Following last month’s focus on The Fugitive Kind, these first releases from new US cult label Scorpion Releasing suggest that something needs to be written about the influence of Tennessee Williams on horror cinema. Williams’ plays – often described as southern gothic and dealing with family secrets, forbidden acts and the dark seeds festering in the heads of sexually blocked outsiders and dowagers – can be seen as an American variation on what J.B. Priestley achieved earlier with his novel Benighted, faithfully filmed by James Whale in 1932 as The Old Dark House. A comparison to the “ghastly elegance of Tennessee Williams” was actually invoked on a US poster for Georges Franju’s Eyes without a Face (1959) but truer heirs to his work would be films such as Walter Grauman’s Lady in a Cage (1963), Jack Hill’s Spider Baby (1968), Gunnar Hellström’s The Name of the Game Is Kill, television’s The Addams Family and, certainly, Freddie Francis’ Mumsy, Nanny, Sonny & Girly (1969), whose Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice-inspired title has been abbreviated for its resurrection on DVD. It and its fellow release, 1970’s Goodbye Gemini, are a serendipitous pairing: two similarly obscure British horror films dating from a time when the screen’s new freedoms had rendered gothic horror passé and in serious need of a transfusion. Though the two films are related only by a shared distributor (Cinerama Releasing), they are both tales of familial decadence, influenced by Williams to different degrees, in which young adult siblings seem to be staving off the temptation of actual incest by committing other transgressions, namely happy-go-lucky acts of murder.

Directed by ex-cinematographer (The Innocents) and self-described horror hack Francis, Girly is based on a Maisie Mosco play called Happy Family and trails an ancestral train that reaches back to The Old Dark House, Tennessee Williams’ Baby Doll (1956), Shirley Jackson’s 1962 novel We Have Always Lived in the Castle and, in some odd respects, TV’s The Prisoner. Young adult siblings Sonny (Howard Trevor) and Girly (Vanessa Howard) use the latter’s Lolita wiles to lure park drunks back to the family manse – Oakley Court, best remembered as the abode of Dr Frank N. Furter – where they are forced to participate in infantile family games and traditions, eventually to be killed under the eye of Sonny’s grinding Super 8 camera or kept on as imprisoned boarders in numbered rooms. Brother and sister find their ideal pawn in the weak, toadyish New Friend (Michael Bryant), whom they frame for the death of his bullying lover (Imogen Hassall) – they’re introduced with the dialogue “You bitch!” “You bastard!” – only to find that he’s authentically responsive to their childish horseplay, their emotional escapism and the erotic rewards doled out by the outwardly prim Mumsy (Ursula Howells) and, eventually, Girly.

Among the most tasteful of cameramen, Francis became one of the most garish British horror directors, sometimes surprisingly void of taste and visual elegance. He personally detested the genre but his few attempts at macabre comedies such as this (another would be 1974’s Son of Dracula with Harry Nilsson) are his hardest to like. The actors (including Pat Heywood as the bisexual Nanny, who sleeps in a drawer at the foot of Mumsy’s bed) are the saving grace of this film, whose comedic aspirations are at times visibly cramped by the cast having to work bare-legged in freezing winter air. That said, Bryant’s portrayal is nicely layered and Howard’s charms – which extend to a memorable close-up during Girly’s first orgasm – are considerable. The film is certainly missing something, but other examples of this odd genus, such as William Castle’s version of The Old Dark House and Terence Fisher’s The Horror of It All (both 1963), had no better luck finding it.

Made the following year, Goodbye Gemini, based on Jenni Hall’s novel Ask Agamemnon, was directed by Canada-born Alan Gibson, 20 years Francis’ junior but whom Francis would outlive by 20 years. Filmed with a smoother, more vital sensibility, it opens with two orphaned adult twins – Julian (Martin Potter) and Jackie (Judy Geeson) – arriving in London to live with a starchy Welsh housekeeper, arranging her fatal trip down the stairs and skipping away carefree from the murder scene. (Agamemnon is their teddy bear, on to which they have projected some kind of otherwise absent parental authority and wisdom.) Despite Julian’s inability to conceal his sexual attraction to his sister, the twins proceed to charm Swinging London with their blond good looks before falling in with a mutton-chopped thrill-seeker named Clive (Alexis Kanner of The Prisoner), who owes £400 to the mob but, rather than save his skin, is hellbent on pressing it closer to Julian’s. There is an unusual emphasis on British gay culture for the time, with more than a few gay characters and female-impersonating entertainers, while Julian’s own homosexual panic gradually builds to an outburst of violence. There’s no mistaking Gibson as the future director of Hammer’s Dracula A.D. 1972; this film, likewise set in Chelsea, has a similarly brass-heavy score, lots of wild party scenes, and stodgy bit parts by old-guard stalwarts to help carry the marquee. As with Girly, it’s not a particularly strong psychological thriller, and it’s similarly hampered by cold-weather shooting, but it’s rich enough in character and performance to keep one watching.

Both films are handsomely rendered on disc, and the extras are conscientious, though both more and less than we need.