Primary navigation

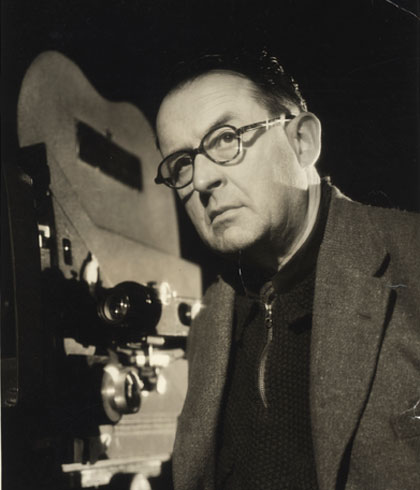

More than any other director bar Hitchcock, the Brazilian Alberto Cavalcanti had a profound influence on British film-making in the 1930s and 40s. But he remains an unjustly overlooked figure, says Nick James

Maybe it’s a truism that many of the most enduring cinematic visions of Britain have been the work of directors from beyond these shores – whether American (Losey), Polish (Polanski), Italian (Antonioni) or Czech (Reisz) – all using their ‘expatriate gaze’ to throw into relief the richness and strangeness of the domestic everyday. But arguably the greatest expatriate influence on our national cinema was that of a comparatively neglected Brazilian film-maker, the most significant figure in British cinema history who still lacks an English-language biography: Alberto de Almeida Cavalcanti. During the 1930s and 40s he transformed the capacities of British film-makers, yet his story is paradoxical, because it calls auteurism into question, and makes a powerful case for the genius of collaboration at a time when British cinema might profit from a return to that ethos.

Though Cavalcanti is one of the most important figures in British film history, and the director of several significant films – including such classic titles as Went the Day Well? (1942) and They Made Me a Fugitive (1947), and the best-known segment of the compendium Dead of Night (1945) – he remains a contentious figure. The documentarian and film historian Paul Rotha, for instance, attacked Cavalcanti’s three years in charge of the GPO Film Unit (from 1937-1940, after its godfather, John Grierson, had left) claiming, “No film told its story clearly… Each started with some universal conception and then led nowhere. It was due, perhaps, to Cavalcanti’s insistence on good technique at all costs.”

The sneer implicit in that statement betrays Rotha’s prejudice in favour of a strictly utilitarian approach to documentary, but he was not entirely wrong. For Cavalcanti, even when he moved to Ealing Studios to assist in making their famous run of 1940s fiction features, was the antithesis of, say, an Alfred Hitchcock. He was always more fascinated by the emotion of individual scenes, by how the effect of that event might be heightened, than he was by the anticipatory need to keep a narrative driving forward.

To see how Cavalcanti came to be so influential in Britain, we must briefly retrace his earlier life. Born in Rio de Janeiro in 1897, he was sent to Geneva to study architecture at the age of 15. But after his father died he gave up the practice and moved to Paris, where he began his film career working for director Marcel L’Herbier as a production designer on Résurrection (1922), before assuming assistant-director duties on L’Inhumaine (1924) and Feu Mathias Pascal (1925). He also worked on Louis Delluc’s L’Inondation (1923) and George Pearson’s The Little People (1926), and edited Marc Allégret’s Voyage au Congo (1926).

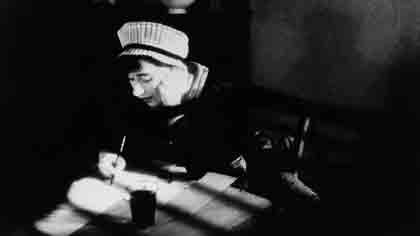

Rien que les heures

By the mid-1920s Cavalcanti was a central figure among the French avant garde, and a friend of the surrealists. His first major triumph came out of a seeming disaster. Creditors chasing his producer Pierre Braunberger impounded the negative of Cavalcanti’s studio-shot debut Le Train sans yeux (on which he had replaced Julien Duvivier). In response, he got together friends to make a cheap alternative shot on the streets of Paris. Rien que les heures (1926) is a documentary avant la lettre (the term ‘documentary’ was coined the same year by John Grierson in a review of Robert Flaherty’s Moana). A playful, multi-layered urban portrait shot with an eye for the bizarre, it anticipates such better-known ‘city films’ as Walter Ruttman’s Berlin – Symphony of a Great City (1927) and Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1928). Prophetically, it opens with the intertitle: “This film does not need a story, it is no more than a series of impressions on time passing.”

However, much of the kudos Rien que les heures won for Cavalcanti was lost by the end of the decade. An enthusiast for the coming of sound, he wanted to learn more about the technology, so in 1929 he began to direct French and Portuguese versions of American films for Paramount at the Billancourt studios. His silent-snob friends did not approve, and his later switch to directing commercially successful comedies for an independent company did nothing to repair his artistic reputation in their eyes. Eventually, in 1933, he sickened of these films himself, and fled to London – into the arms of John Grierson and his newly established GPO Film Unit.

Though it’s the British films involving Cavalcanti that concern us here, it’s worth pausing to consider the influence of his years in the French film industry. His knowledge of sound and his strange modernist juxtapositions were what attracted Grierson – alongside, of course, the cachet of his connection with the surrealists. But while Cavalcanti always displayed a certain offbeat whimsicality of approach, those surrealist credentials shouldn’t be overemphasised. The Brazilian would prove, in the long run, to be just as much an adherent of French poetic realism as such former confrères as René Clair, Julien Duvivier, Jean Grémillon, Marcel Pagnol and Jean Renoir.

Cavalcanti’s memory of his journeyman years in France was matter-of-fact: “We shot strictly to very tight scripts and, as we had no money to spare, we couldn’t improvise.” Later, at Ealing, when someone suggested that one scene in Went the Day Well? was “too dark”, he replied: “I’ve been making films in France for years and years where nobody could see nothing, and everyone was delighted.”

An amateur lot

The leap from the avant garde to Grierson’s documentary movement has often been regarded as anomalous, but in fact Cavalcanti’s transition was more congenial than it appears. A film-maker who was schooled in L’Herbier’s silent-era ‘impressionism’ and spoke little English might seem a strange choice to bring into the fold with Grierson’s supposedly strict bunch of socialist zealots, whose rhetoric insisted on documentary being about ‘social utility’ and ‘civic education’. But then, as Brian Winston argues in his book Claiming the Real, Griersonian documentaries looked to poetic effects even before Cavalcanti arrived.

Pett and Pott

“The search for the picturesque is to be found in even the least ‘aesthetic’ subjects,” argues Winston. “Like Flaherty before him, Grierson did not seek out an alternative documentary-specific code to represent time and space. Both were content with the legacy of Hollywood, not least because dramatisation was seen as being essential to the form.” Winston’s point that all documentary is, to some extent, drama-doc is undeniable; but the picturesque, in this context, is also connected with the French idea of photogénie found in the writings of Louis Delluc, Louis Aragon and Jean Epstein. As defined by Michael Chanan in The Politics of Documentary, photogénie “means more than ‘attractive to the camera’… [it’s] also a sense of transcendence which film lends to the phenomena under observation, a shimmering that gives us the impression of seeing things as we’ve never seen them before”.

It was Cavalcanti’s job to help the GPO Film Unit achieve just such poetic effects, and his arrival did indeed have an enormous impact on the approach of the young film-makers gathered there. This is not the place to go into the unit’s whole output (the BFI DVD collections ‘Land of Promise’ and the three volumes of ‘the GPO Film Unit Collection’ cover it comprehensively). Suffice to say that he was a crucial influence on film-makers as diverse as Humphrey Jennings, Basil Wright, Harry Watt, Len Lye and Norman McLaren.

The admiring way in which many of these young documentarians spoke about ‘Cav’ – as they soon nicknamed him – anticipated what his future colleagues at Ealing would say. According to Watt, “The arrival of Cavalcanti... was the turning point... British documentary films could not have advanced the way they did without him... [Before him] we were really pretty amateur.” For Charles Hassé, a close aide, Cavalcanti was “so warm-hearted… He listened to whatever you had to say and improved what you had to say in a way too.” Or as Joe Mendoza, assistant director on Jennings’ masterpiece Listen to Britain (1942), commented: “Cav got people to think analytically about what was on the screen and on the succession of images, and why it went flat there and nothing happened and why it got better there.”

The Brazilian himself was drawn to the communal ideals of the unit’s office in Soho Square and studio at Blackheath. “We worked,” he wrote, “in conditions that were similar to those of craftsmen in the Middle Ages. The work was collective, and each person’s films were discussed by everyone else. If the film of a companion required some assistance, it was offered. However, each team retained their own profile, within a spirit of healthy competition.” What Cavalcanti didn’t like was the word ‘documentary’: in his 1952 book filme e Realidade, he would say it had “a taste of dust and boredom” – and claim that he had suggested the term neorealism to Grierson some time in the 1930s.

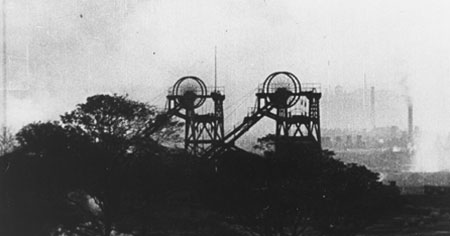

Coal Face

The GPO shorts credited to Cavalcanti as director include Pett and Pott (1934), a suburban satire and neatly disguised advertisement for the telephone, with its bowler-hatted synchronised drones shuttling by tube to Willesden Green, and Coal Face (1935), a meditation on a miner’s life with highly inventive musical content and sound effects (including contributions from poet W.H. Auden and composer Benjamin Britten) accompanying stark industrial imagery. But Cavalcanti was also closely associated with Night Mail (1936), that epic collaboration of talents (including Auden and Britten again) credited to co-directors Harry Watt and Basil Wright (Cavalcanti received a credit as sound director). What seems most innovative about these films in the context of Britain is indeed, as Rotha says, their technical excellence: the audacious use of sound and music integrated into the rhythms of action and sharp editing. Given how entangled ideas of surrealism and Monty Pythonesque humour have become, it’s harder now to distinguish English eccentricity from French absurdism, but in Pett and Pott, for instance, the two exist simultaneously.

Tracing Cavalcanti’s influence beyond the films that bear his name is made more difficult by the unit’s deliberate disregard for credits. “We kept on putting on the names of the young people,” said Grierson, “not the names of the people who were concerned. There were years when Cavalcanti’s name never went on a picture.” One gets a whiff here of the part-admirable, part-condescending high-mindedness that must have made the place reek of parlour socialism and public-school camaraderie. But Cavalcanti relished what Grierson had put together: “Seeing how devoid of national character the early British films were, and how close to theatrical or literary conventions British film people used to stick… one could sense what a bunch of determined young people could do to change it all.”

When Grierson left the unit in 1937, Cavalcanti got his chance to show what it could do. He believed that “without experiments, the documentary loses its value” – and arguably, through the imaginative variety of the films he oversaw (and through the career of Humphrey Jennings in particular), he proved a decisive influence on an entire generation of British film-makers.

A highly civilised man

Why did Cavalcanti leave the GPO unit for Ealing in 1940? There are conflicting reports. The unit was taken over by the wartime Ministry of Information, and it’s said they wouldn’t allow their new propaganda unit to be run by a Brazilian homosexual. Cavalcanti was peeved. “I was a foreigner,” he said. “The GPO people wanted me to become a naturalized British subject… I had been practically in charge at the GPO and they put someone in my place.” But his version is called into question in Charles Drazin’s The Finest Years: British Cinema of the 1940s by a memo written by the unit’s general manager to the MOI: “Mr Cavalcanti,” it states, “is without doubt the best Producer in the country and it is vital that the film unit should continue to have use of his services.” Drazin also suggests that Ealing’s Michael Balcon may have recruited Cavalcanti so that his studio could “have some kind of a tie-up” with the unit.

Whatever the real reason, Cavalcanti resigned and joined Ealing, where he would earn more money and have the chance to make fiction films again. With a ‘new realism’ as his goal, Balcon prized Cav’s propensity to see fiction and documentary as fluidly interchangeable forms. “[Cavalcanti] was a highly civilized man… a particularly outstanding figure,” Balcon later wrote. “Of all the group… Cavalcanti was the most important and the most talented.” Given this opinion, it is curious that Cavalcanti features so scantily in Charles Barr’s seminal book Ealing Studios, which argues so forcefully for the Britishness of the Ealing project that the Brazilian’s contribution is sidelined.

Yet if one remembers the description of Cavalcanti as “the best Producer”, and looks at the British films he directed at Ealing, one can see why he doesn’t make Barr’s list of the six centrally important Ealing directors (though his GPO acolyte Harry Watt does). It’s not so much that he’s a foreigner – more that the films he directed are too wide-ranging to allow conventional constructions of authorship.

Barr describes Cavalcanti’s best-known British film Went the Day Well? as “part of a loose trilogy” that includes two other Ealing films from 1942, The Foreman Went to France and The Next of Kin. What links them, Barr says, is the sense that “the threat of an enemy all around enforces resource and alertness, and penalises complacency and amateurism”. But the very looseness of this trilogy also illustrates the collaborative nature of Ealing and the complexity of the influences at work in all the studio’s films. The Next of Kin, about a raid on occupied France that the Germans intercept because of ‘loose talk’, was directed by Ealing outsider Thorold Dickinson, who also scripted alongside studio regulars John Dighton and Angus MacPhail. The Foreman Went to France, about a factory foreman determined to retrieve important machines on loan to a French company when the Nazis invade, was directed by Charles Frend, from a script by Dighton, MacPhail and Leslie Arliss. In his autobiography Balcon claimed that, “What made The Foreman Went to France noteworthy was Cavalcanti’s influence.” He was “wonderful on the film”. Penelope Houston, in her succinct monograph on Went the Day Well?, shows how “[The Foreman] shares with Went the Day Well? both its flashback structure and some of those sudden swings of mood that are liable to turn up in a MacPhail/Dighton script. Impressively strong scenes, such as the strafing of the refugees… by German planes… are slammed up against larky adventures with opponents who are much too easily outwitted… It is carried along by a kind of careless energy, a determination to keep going and get there.”

Went the Day Well

All of which means that Went the Day Well? itself, although directed by Cavalcanti, is just as much of an authorship conundrum as any other Ealing film. Originally given the unfortunate title They Came in Khaki, it was loosely based on a very short Graham Greene story. MacPhail and Dighton were again present for script duties, alongside Diana Morgan – who said her job, in the suburban studio’s boys’-school atmosphere, was adding sentimental touches (or, as the ‘boys’ quipped, “putting in the nausea”).

Yet there’s not too much in the way of sentimentality in this stark film about the meaning of resistance. Went the Day Well? opens in an English village graveyard with the verger telling us how one gravestone in Bramley End came to bear a list of German names. In flashback we see the arrival of army trucks filled with Royal Engineers, all of whom need to be billeted. At first relations between the villagers and the soldiers conform cordially to the stereotypes found in Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple stories – although one soldier reacts with too much force to a cheeky young scavenger. But clues left clumsily in view of the vicar’s daughter Nora (Valerie Taylor) – a game score that uses a continental number seven, and a bar of chocolate branded “Chokolade Wien” – pique her curiosity. She tells the local squire (Leslie Banks) – unaware that he is the resident fifth columnist. The soldiers then reveal themselves for what they are: German paratroopers in disguise.

Great play is made of the villagers’ switch from conviviality to murderousness. The narrative mainly concerns their efforts to escape the church, where the Germans have them under guard, to get a message to the real British army. But as with any Cavalcanti film, the plot is secondary to the human business of moral choices; each inhabitant, in that Ealing way, has his or her own moment of decisive action. The telephonist, for instance, doesn’t hesitate to put an axe into ‘her’ Nazi while he’s eating the ‘tea’ she’s made him.

Similar “swings in mood” to those in The Foreman abound here, if more plausibly. Cavalcanti would later try and claim Went the Day Well? as a pacifist film, but though it’s touching and quirky – and quintessentially English – it is above all a successful propaganda piece designed to push the correct attitudes to a possible invasion (even if that invasion was unlikely by the time of its release). The ideal community here is as much a self-defence killing machine as it is a symbiotic group of caring neighbours – and the film’s curious sense of fun derives from that double standard.

Champagne Charlie

Cavalcanti’s other Ealing credits were typically sporadic and eclectic. He directed two more features that demonstrate his range but reveal his weaknesses, and a feature segment that outclasses much of his work. Champagne Charlie (1944) is a musical of considerable elan, excellent at delineating the music-hall world (from a perspective that’s more Lautrec than Sickert) but reliant on Tommy Trinder and Stanley Holloway as rival music-hall turns whose fame derives from drinking songs. Cavalcanti keeps up the “careless energy” as we bounce from ‘Ale Old Ale’ to ‘I Do Like a Little Drop of Gin’, from ‘Burgundy, Claret and Port’ to ‘Rum, Rum, Rum’, ‘A Glass of Sherry Wine’ and then finally to ‘Champagne Charlie’.

It was Cavalcanti’s misfortune to tackle Nicholas Nickleby (1947) in between David Lean’s two hard-driving Dickens adaptations, Great Expectations (1946) and Oliver Twist (1948). Set among inky shadows, Nickleby’s brisk telling here, with its ‘characterful’ speeches, seems more pompous than dramatic. Cavalcanti’s better fortune was to contribute one of the segments of that keynote omnibus of British supernatural cinema, Dead of Night (1945). ‘The Ventriloquist’s Dummy’ tells of the jealousy that builds in the soul of a ventriloquist (a haunted Michael Redgrave) because his dummy, which at times seems to have a life of its own, insists on flirting with a rival ventriloquist. After a violent attack, the rival is told that the ventriloquist is suffering from a dual personality. Filmed with typical Cavalcantian deftness, it’s a splendidly unnerving short film – which anticipates the ending of Hitchcock’s Psycho.

Cavalcanti’s career wasn’t over when he left the UK in 1950, but it is at that moment we will leave him. He would return home to Brazil to try to set up something as collaborative as Ealing – and fail (at least in the short term), in part because the age of auteurism would be upon him. Some of those who have seen his Brazilian work claim, however, that with O Canto do Mar (The Song of the Sea, 1952) he finally achieved the cinema he’d been working towards. Not having seen it, I can’t say. But there is an earlier film that feels to me like Cavalcanti coming home, at least in stylistic terms – a film he made in Britain for Warners after he left Ealing, and following a demoralising visit to a venal post-war Paris.

They Made Me a Fugitive

They Made Me a Fugitive is simultaneously a crucial British film noir, an excellent European poetic-realist fugitive film and a prime example of the ‘spiv cycle’. Clem Morgan (Trevor Howard) is a former RAF pilot with “too much animal spirits” and Narcy – short for Narcissus – (Griffith Jones) is a spiv criminal boss who’s going to supply him with action. But when they meet to seal the deal, a drunk Morgan (twice) introduces Narcy to his “popsy” Ellen, who spies a better opportunity in the preening gangster. Morgan settles into the work, but makes the mistake of criticising his touchy employer for dealing in “sherbet” (narcotics). During a robbery, Narcy has a policeman run over and frames Morgan for manslaughter. In Dartmoor, Morgan is antagonised back into action by a visit from Narcy’s ex-girlfriend Sally (Sally Gray). He escapes and heads for London and an eventual showdown, taking in a few on-the-road incidents, including an offer from a blind woman to murder her husband in exchange for money.

There is much that is dark here – way too dark for Ealing. Narcy has a sadistic side, especially in his pimp-like treatment of women. He threatens Sally, for instance, with a beating from a Bill Sykes-like associate wielding a huge belt and buckle. Howard is so adept at simply being on screen, he almost allows Jones’ Narcy to steal the picture. But the film itself is imbued with that poetic-realist sense of darkness as a fatalistic stain or stigma. It is also photographed so beautifully by Otto Heller that there are moments of undoubted photogénie. In fact it’s about as fine a Brazilian British film as you could wish for.

A Cavalcanti retrospective plays at BFI Southbank, London throughout July, including extended runs of ‘Went the Day Well?’ and ‘They Made Me a Fugitive’, both restored by the BFI National Archive with funding provided by The Film Foundation. The restorations are part of ‘Long Live Film’, a celebration of the Archive’s 75th anniversary.

In search of poshlust times: Nick James on the ambitious, high-culture art films of Joseph Losey and Harold Pinter (June 2009)

Going underground: Billy Elliot screenwriter Lee Hall on the BFI National Archive's treasure trove of films about the mining industry (October 2009)