Primary navigation

Germany/France 1988

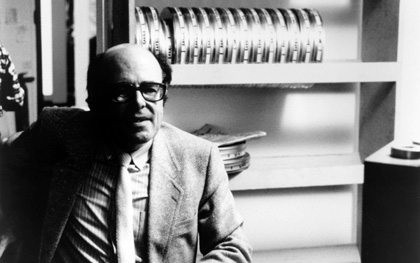

Reviewed by Nick James

Hotel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie

Marcel Ophuls; Germany/France 1988; Icarus Films / Region 1; 267 minutes; Aspect Ratio 4:3; Features: booklet

This remarkable audiovisual dossier is ostensibly a talking-heads marathon about the background to the trial of Klaus Barbie, the ‘Butcher of Lyon’. As the head of the city’s Gestapo from 1942-44, Barbie was responsible for many atrocities – including the torture and murder of resistance hero Jean Moulin – and yet he was allowed by the Allies to escape justice for 40 years until his extradition from Bolivia to France in 1983 and his trial in Lyon the following year. However, this gradual unpeeling of the layers of complicity that were wrapped like tissue paper around Barbie is merely the pretext for a deep intellectual delving into the moral unease that surrounds the most fundamental questions of personal guilt arising out of World War II.

I first saw Hotel Terminus at the London Film Festival in the late 1980s. Then it seemed a contemporary work; now it’s more like a time machine from an age when every person interviewed, no matter how much they had to hide or how mendacious they were, seems to feel a responsibility to the truth – even when they’re lying. Watching it now, you realise that there really was once a world without spin. Ophuls can quiz a US State Department official or a former US intelligence officer and get either straight answers of utter candour or straight answers of utter cant. What you don’t get are the bland locutions of cynical stonewalling and blindsiding that the most recent era of western adventurist politics has left as its legacy.

The film shows complete respect for the viewer’s intelligence, plunging you straight in with a still image of Barbie and then a cut to one of his cordial German neighbours from Bolivia recalling with incredulity how Barbie (then renamed Altmann) got mad at any slur on the name of his long-dead Führer, and then another cut takes you to a billiard room in Lyon, where various patrons describe what Barbie’s trial means to them. Over the next four hours and more, there’s no spoon-feeding of context, you have to put the puzzle together yourself.

And what a puzzle. Barbie, to the several friends who never saw him in what we might call his professional context, was a kind, caring, jolly and affectionate friend or relative. Victims of his torture regime recall a small, calm man who would burst into a vicious splenetic rage. In terms of subtle character analysis, the film’s nearest literary achievement would be Gitta Sereny’s Albert Speer: His Battle with Truth. There is a cameo appearance from Claude Lanzmann, maker of the landmark holocaust 1985 documentary Shoah. And it’s remarkable how many subjects of other films turn up – for instance, the slippery anti-colonialist lawyer Jacqes Vergès, subject of Barbet Schroeder’s 2007 documentary L’Avocat de la terreur, and Lucie Aubrac, the eponymous resistance-heroine subject of Claude Berri’s 1997 drama. One man who escaped Barbie by pretending he didn’t understand German was the linguist Michel Thomas. In this context these are the good guys. But Ophuls, an almost magical interlocutor, is seemingly sympathetic to every interviewee, no matter what their political persuasion. Yet he’s also unafraid of asking the most pointed questions. He’s no purist, though; he doesn’t hesitate to help those on the brink of unthinking confession by offering the word they’re grasping for. They’re almost always grateful.

No part of any film I’ve seen has stayed with me quite as indelibly as the final scenes of this documentary, in which one of the very few children of the 44 from of the Izieu orphanage whom Barbie sent to the death camps returns to the building from which she was snatched. I won’t describe the sequence in detail, but the question it raises is what any one of us would have done had we been faced with the moral dilemmas rife in occupied and Vichy France. It’s a more fundamental question for westerners now – in the midst of revelations about the behaviour of British and American servicemen in Iraq – than what one might have done had one been born in Germany at the wrong time (that cultural psychosis – so carefully imagined in Michael Haneke’s The White Ribbon – seems to have been too damningly powerful for almost anyone to escape). Any specific set of cultural circumstances is impossible to repeat, but the French circumstances produced complex responses to the threat of terror and intimidation that seem more ‘human’, and therefore more available to analogy.

As children, many of us who grew up in the post-war West fantasised about the war. Popular culture was full of the romanticised exploits of our parents’ generation, from War Picture Library comics to Airfix kits of Spitfires and Messerschmitts, to war movies such as The Longest Day (1962) and 633 Squadron (1964). For myself, the heroic group that appealed the most in these schoolboy games – no doubt for trivial or romantic reasons – was the French Resistance.

In the immediate aftermath of the war the idea of the Resistance was crucial for French morale. However, Marcel Ophuls’s landmark documentary The Sorrow and the Pity (1969) – which makes a kind of diptych about the occupation in France with Hotel Terminus – is one of the key documents that undermined the myth of a general French resistance. Most of the population were accepting of the status quo and the Resistance did not become a significant force until the Germans demanded forced French labour for its industries. Only then did droves of young men flee to the hills in search of protection and a cause.

In one moment in The Sorrow, Ophuls notes that it was people on the fringes of society, the loners and outcasts, who resisted from the start, not those with vested interests – an observation that should give any one of us pause to wonder how we ourselves would have behaved. By the end of The Sorrow and the Pity we are only too aware of the accommodations that gave people’s lives a sense of normality and convenience. In Hotel Terminus, Ophuls uses his extraordinary skills as, yes, an interrogator to build from the earlier film’s platform of moral self-doubt and present us with a parcel of plutocrats in as many shades of sideways complicity with Barbie as can be imagined. “It was 40 years ago,” is the constant refrain offered as a reason to forget. But fortunately this film is unforgettable.

Unexpected tenderness: Catherine Wheatley sees hints of a new softness in Michael Haneke’s work (December 2009)

Documentary: shaking the world: Mark Cousins proposes ten films that made a real difference (September 2007)

Apt Pupil reviewed by Kim Newman (June 1999)