The Gilbert Adair files

One elephant, two elephant:

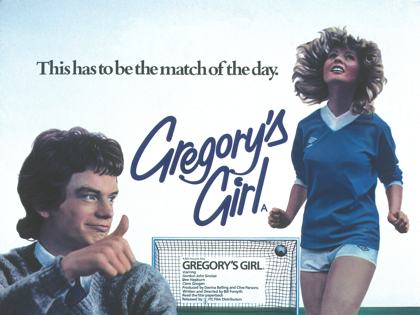

That Sinking Feeling and Gregory’s Girl

From Sight & Sound Summer 1981, pages 206-207

Editor’s note:

Although he would doubtless have liked people to think of him as essentially French, Gilbert Adair was in fact Scottish, born in Kilmarnock on 29 December 1944. He was cagey about life prior to his Paris emigration in 1968, and rarely mentioned Scotland in print (though he retained a trace of the accent), but this Sight & Sound review of Bill Forsyth’s first two features betrays insider knowledge. Amidst the namechecks of Godard, Rohmer, Tati, Truffaut and even Lévi-Strauss, he also observes “such assorted miscellanea as apple slab, Irn-Bru, san’shoes and Partick Thistle”, and concludes with a tribute to compatriot Chic Murray.

— Michael Brooke

Bill Forsyth’s second film, Gregory’s Girl, is set in and around a pleasant comprehensive school in a New Town near Glasgow. Early on, while our attention is focused on foreground activity of some import to the plot, a small boy in a penguin costume is glimpsed wandering along one of its corridors, before vanishing as abruptly as he appeared. What that capsule description omits, however, is the almost subliminal level at which the gag properly functions: though our immediate perception is of a penguin, albeit an oversized one, our laughter is provoked less by its incongruity than during the fraction of a second which elapses before we conclude that, under the circumstances, it can only be a disguise (perhaps for an end-of-term play). Later, apparently lost, the penguin resurfaces to be directed by the headmaster to the classroom where his presence is mysteriously requested. At which point, we may already suspect that the penguin’s identity and raison d’être are forever to be withheld from us. But what we are unlikely to anticipate is that he will make a third appearance, one which by exactly duplicating the particulars of that preceding it – the by now forlorn wee creature is steered once more towards his elusive destination – would seem to be breaking a basic rule of visual humour. Yet the effectiveness of the joke this time paradoxically depends on our failure to respond to it as such. For we have come to accept the penguin as a familiar and even reassuring element of the school’s curricular routine: that he is no longer funny is funny.

If I have made so much of a single gag, in a film crammed with gags, it’s not merely for the pleasure of reminiscing about it in print but also because, within its modest narrative framework, Gregory’s Girl strikes me as a well-nigh flawless comedy, and perfection is a much trickier concept to come to terms with globally than in an isolated detail. For this reason, the delayed release of Forsyth’s first film has served at least one purpose, that of clearly demonstrating the distance since covered by its director.

That Sinking Feeling deals with a group of Glasgow slum urchins who, faced only with the disheartening prospect of no prospects (“There’s gotta be more to life than committin’ suicide”), devise a foolproof plan to burgle a local plumber’s warehouse of ninety stainless steel sinks. And, for a first film, it boasts an extraordinary variety of comic tropes: running jokes (the addiction of the scheme’s begetter to cornflakes, inside a bowl of which he contemplates drowning himself); exquisitely timed bathos (two of the plotters warily clam up until the tiniest of tiny tots has waddled out of earshot); verbal non sequiturs (when, during the heist, one of the gang claims possession of a gleaming new lavatory pan, he is promptly ordered to return it as, for some unfathomable reason, “These things are too easily traced”); and a few Tatiesque visual rhymes (two youths who appear to be indulging in fisticuffs are in reality attempting to ward off a swarm of marauding bees).

A pity, then, that its too frequent lapses into nudgingly facetious whimsy, already foreshadowed by an arch (and not very original) mock-disclaimer that the Glasgow setting should not be confused with any real city of that name, tend to swamp the more delicate trouvailles – most notably on the subject of role reversal which, developed in Gregory’s Girl, would seem to herald the inception of a Forsythian thematique. In order to distract the warehouse’s night watchman, two of the gang have to masquerade as coyly simpering charladies, roles into which they slip with disturbing ease. But because of an excess of repetitive vaudevillian mugging, the ensuing imbroglio – the watchman’s flirtatious attentions to one of the decoys arousing in the other all the fury of a female impersonator scorned – quite dissipates the potential of that ambiguity, and the scene is reminiscent of an indulgently off-colour skit in a school concert.

Gregory’s Girl, however, manages to invest the same theme with both humour and resonance. Dorothy, the gorgeous centre forward, initially catches Gregory’s eye as much by her dribbling skills as by the way her pawky volupté is displayed to advantage on the soccer field; and when her goal-scoring is greeted with the traditional sweaty embrace from the (otherwise all-male) team, he mutters “Perverts!” from the goalmouth. In direct contrast is the treatment of Steve, Gregory’s confidant, whose knack for pastry-making (“The doughnuts are selling like hotcakes!”) and apparent indifference to either sport or girls set him slightly apart from his more boisterous chums. When asked by euphoric Gregory if he has ever been in love, Steve, visibly trembling on the brink of a revelation (and perhaps of self-realisation), is rescued only by the garrulity of his friend’s own amorous discourse. Forsyth’s not inconsiderable achievement here, aided by a remarkably sensitive performance by William Greenlees, is to have created a character no less perplexed by his sexuality than is the spectator.

But the whole film is enhanced by these modulations from the overt to the latent, or between what Lévi-Strauss termed “the raw and the cooked”, in a manner comparable to, and worthy of, early nouvelle vague. The slender but affecting storyline – Gregory, at first infatuated with Dorothy, is slyly shunted from schoolgirl to schoolgirl till he falls straight into the arms of Susan, the one determined to hook him from the beginning – possesses much of the lapidary elegance we associate with Rohmer’s contes moraux. Though Forsyth’s social observation is far cannier than Truffaut’s (he makes wonderfully evocative use of Scottish faces, landscapes and such assorted miscellanea as apple slab, Irn-Bru, san’shoes and Partick Thistle), it’s possible to be reminded of Truffaut by the haunting transition that whisks us across town from Gregory’s bedroom to Susan’s, where she lies snuggled up in bed presumably dreaming of him. As for the Godardian epiphany when, stretched out on the grass, the couple persuade themselves that they can feel the earth’s rotation, and Forsyth gently tilts the image to prove them right, it succeeds (as Godard’s rarely did) in keeping their fleeting apprehension of cosmic immensity firmly rooted in a common, almost humdrum, human experience.

Still, Gregory’s Girl is above all a comedy, and an even more eclectic one than That Sinking Feeling. Forsyth’s dialogue now ranges from the suggestively Pinteresque (“What about Alan? D’ye think he’s a virgin?” “Och no, he’s been in the school orchestra for over a year now”) to the plain delirious (the amateur photographer’s obsession with the word ‘elephant’ which, taking exactly one second to utter, is therefore useful for timing in a dark room); and at least one of his visual gags, surpassing even Keaton and Tati, approaches purity (in the exposed centre of an empty playground, Gregory, late for class, heroically endeavours to conceal himself behind nothing). From a uniformly delightful cast no one should be singled out. But special mention really has to be made of Chic Murray, a well-known Scottish comedian who plays the headmaster and, with a film-stopping (as one says “show-stopping”) piano solo, offers us a couple of minutes – or one hundred and twenty elephants – of sheer bliss.

See also

Introduction: Michael Brooke introduces our Gilbert Adair tribute trove (December 2011)

Early reviews: six of Adair’s early capsule reviews from the Monthly Film Bulletin (1979-80)

The rubicon and the rubik cube: Adair on exile, paradox and Raúl Ruiz (Winter 1981/82)

Memories of youth, anticipations of maturity: Adair’s reviews of La Luna and The Outsiders (Winter 1979-80 and Autumn 1983)

Meandrous expeditions: Adair’s reviews of Stalker and E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (Winter 1980/81 and Winter 1982/83)

Adair on music: reviews of Amadeus, Carmen and Ginger & Fred (Spring 1985, Spring 1986 and Monthly Film Bulletin March 1985)

The Nautilus and the nursery: Roland Barthes’s [sic] April-Fools paean to the Carry On cycle (Spring 1985)

Double takes: Heurtebise: Adair’s pseudonymous contributions to Sight & Sound’s Double Takes column (Winter 1984 to Summer 1985)

Favourites: select Adair celebrations of Jean Cocteau, Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet and Robert Bresson (Autumn 1981; Spring 1985; Summer 1987)

Gilbert Adair’s Top Ten films (September 2002)

The Dreamers reviewed by Ginette Vincendeau (February 2004)