Reviews

Human Rights Watch Film Festival 2011 documentaries

Jump to a review:

» Impunity

» When We Leave

» ¡Women Art Revolution

» You Don’t Like the Truth – Four Days Inside Guantanamo

Impunity

Juan José Lozano, Hollman Morris

Colombia / France / Switzerland, 2010

85 minutes

Colombia’s political quagmire and dire human-rights record have been pressing concerns for decades now, the many documentary and fiction-film treatments threatening to render us numb through over-exposure. Yet under the expert direction of Lozano and Morris, Impunity gets right under your skin.

The film focuses on the hearings that formed part of the Commission for Peace and Justice, established in 2005 in the wake of over 30,000 paramilitaries handing in their arms. Key confessions are interspersed with amateur footage shot by the police and paratroopers themselves. We also hear gruesome details of the chilling testimonies of victims’ relatives and a series of talking heads attempting to explain the increasingly complex political repercussions of this very process.

Most interestingly, Impunity evokes the surreal, detached atmosphere in which the actual proceedings took place. Watching the proceedings live on screen from an adjoining room, the victims are given a microphone and take turns to ask the accused about their missing relatives, coached into speaking (or indeed, not speaking, as one witness complains) by psychologists and other officials in the background.

When the numerous massacres are revealed to be part of a land grab orchestrated by politicians and other powerful people, the hearings become a standard cataloguing of testimonies and exhumed bones, handed over to relatives in a grotesque ceremony. (Despite international intervention and the paratroopers’ confessions, the accused have yet to go to trial, more than five years after the process started.) A poignant and restrained account of a terrible era in Colombian history, Impunity is elevated by the testimony of its peasant witnesses; their testimonies, integrity and humility reverberate.

Mar Diestro-Dópido

When We Leave

(Die Fremde)

Feo Aladag

Germany, 2010

119 minutes

In Austrian actress Aladag’s directorial debut, Umay (Sibel Kekilli) – a fiercely independent lady of German birth and Turkish parentage – deserts her abusive husband in Istanbul and flees, young son in tow, to her family in Berlin. There she hopes to carve out a new and freer life for herself and her son; but her rigidly orthodox Muslim family, taking Umay’s desertion as a blow to their honour, have different ideas.

Aladag was moved to make When We Leave after Germany was shaken by a spate of honour killings in Muslim families. Her agenda is clear – she’s calling for Islamic doctrine to relax its position on the woman’s obligations to her family – but her film suffers from stereotyping as a result. Her Germany is populated by sexually emancipated women and kind, sensitive men, and Umay and her unfeeling family sometimes slip too easily into the roles of goodie and baddies respectively, a problem which isn’t helped by some stilted supporting performances. And a more searching film might have looked at how the family’aQs faith ties into or has been affected by German society, of which Muslims only make up around four per cent.

But this menacing work is saved from its occasional dips into melodrama by an appealing performance from Kekilli. As Umay breaks away from her family, Aladag subtly brings out her latent sexuality, which is juxtaposed with her parents’ misogynistic denunciation: “Once a whore, always a whore.”

Alex Dudok de Wit

¡Women Art Revolution

Lynn Hershman Leeson

USA, 2011

83 minutes

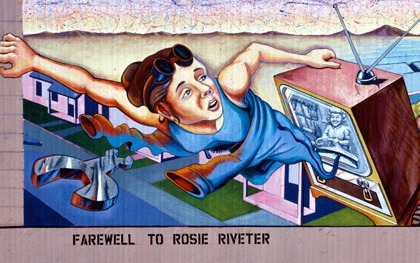

Images of performance art, direct action and reclaimed space flash through Hersham Leeson’s energetic portrait of the US feminist art movement from the 1960s to the 90s, while artists, academics and critics provide a commentary acknowledging both the achievements and tensions that rippled out from the first-wave feminist explosion.

There is audible and deserved pride in the testimonies of Marcia Tucker, Rachel Rosenthal, Judy Chicago and countless more. In an age of high-profile female curators and major retrospectives of Yvonne Rainer and Nancy Spero (both interviewed), it’s easy to forget how women struggled to be seen and heard in a climate of minimalist art and theoretical blind-alleys – nicely skewered in Nancy Buchanan and Barbara T. Smith’s Please Sing Along (1974), in which the two women wrestle in front of a man spouting academese. Hershman Leeson shows how early gestures grew into structural changes such as women’s art programmes at universities; while drawn to the media-friendly Guerilla Girls and controversies like Chicago’s ‘pornographic’ 1979 installation The Dinner Party, she also attempts to show the very different experiences of Black and Latino artists like Howardena Pindell, Judith Baca and Ana Mendieta.

Hershman Leeson’s role as an artist preoccupied with identity adds an interesting layer to this simply structured film. Not only did she presciently shoot many of her interviews in the 1970s and 80s, her early ‘investigations’ saw her take on personae including a fictional art critic: her presentation of her contemporaries is, while celebratory, also knowingly subjective. Countercultural movements are often portrayed as tidy ‘year zero’ revolutions; Hershman Leeson’s note that ¡Women Art Revolution is edited from 12,345 minutes of footage is a warning against such nostalgic versions of historical truth that’s well in keeping with her film’s subject matter.

Frances Morgan

You Don’t Like the Truth: Four Days Inside Guantanamo

Luc Côté, Patricio Henríquez

Canada, 2010

99 minutes

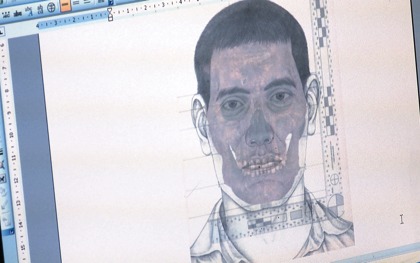

In 2002, 15-year-old Canadian Omar Khadr became the youngest ever inmate of the Guantanamo Bay detention camp after being charged with the murder of a US soldier in Afghanistan. Months after his incarceration, Canadian officials were permitted to interrogate Khadr over four days; this film weaves the recently declassified footage of the proceedings together with interviews with individuals connected to the case.

Directors Luc Côté and Patricio Henríquez (whose backgrounds are in sociopolitical documentary) provide a case study of the iniquities of the Guantanamo system, drawing on interviews with psychologists, lawyers and former soldiers and inmates to bolster their argument. The tone is objective and remarkably unsentimental: there is no voiceover, no flashy visuals, and no music but for some ominous industrial noise at the end.

The directors nevertheless bring out the dramatic narrative in Khadr’s interrogation. The interrogators are at first deceptively friendly, presenting themselves as Khadr’s saviours. But as they turn more hostile, and their true agenda – to extract a confession from Khadr that can be used against him in court – becomes apparent, the filmmakers track the breakdown in communication with stark chapter titles: “Hope”, “Fallout”, “Blackmail”, “Failure”.

The film benefits from some astonishingly candid talking heads. Even the most extreme testimonies – such as that of former US soldier Damien Corsetti, who confesses to having used “cold and callous” interrogation techniques on prisoners – are delivered matter-of-factly. In such an emotional film, the only tears shed are Khadr’s, in a harrowing scene where he breaks down once his interrogators have left his cell.

Côté and Henríquez are to be commended for their sober approach to this controversial subject, which is all the more topical in light of Obama’s recent decision effectively to keep the detention camp open. It’s also good to see a documentary that for once scrutinises Canada’s complicity in the Guantanamo system. Let’s hope a similar film will soon be made from a British viewpoint.

Alex Dudok de Wit

See also

IDFA 2010 reviews: Arab Attraction, The Green Wave, Holy Wars and Utopia in Four Movements (November 2010)

Sheffield Doc/Fest 2010 reviews: The Embrace of the River, Marwencol, Nostalgia for the Light, On the Streets, Scenes from a Teenage Killing and Vapor Trail (Clark) (November 2010)

Rain, speed dates, glamour and fine films: Edward Lawrenson’s postcard from Sheffield Doc/Fest (November 2010)

Every doc for itself: documentaries with attitude, and filmmakers with vision: the worst and best of Sheffield Doc/Fest 2009 (November 2009)

Documentary: shaking the world by Mark Cousins (September 2007)