Blood Symbol

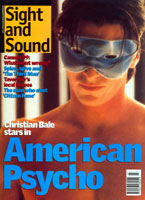

They called it the "impossible project" until Mary Harron took it on. Then it was a Leo DiCaprio vehicle and Harron was dropped. Now she's got it back. Jeff Sipe reports from the set of American Psycho

It's a few minutes past 5pm and the residents of an Upper West Side apartment building in New York City are arriving home from work. Their puzzled expressions make it clear they paid little attention to the notices left in their mailboxes a few days earlier. Otherwise, no one would be surprised to find the spacious, marble-walled lobby packed with klieg lights, sound equipment, a couple of cameras, headset-bedecked production assistants and a host of eclectically dressed crew members.

An assistant director shouts, "Quiet!" The murmur of voices dies down, the sound of shuffling feet dissipates and the command "Action!" rings out. From the rear of the lobby a handsome young man in an expensive overcoat, his brown hair perfectly coiffed, makes his way forward. His gait is slightly uneven, burdened as he is by a bulging blue nylon sleeping bag. Midway across the lobby he stops and glances back at the bag. His face registers a flicker of concern at the trail of blood that has leaked on to the pristine floor. He turns around, readjusts the bag and continues walking.

"Is that the psycho?" the building's green-uniformed doorman asks me after "Cut!" is shouted.

"That's him," I answer.

Actor Christian Bale doesn't register with the doorman until I remind him he was the little boy in Steven Spielberg's The Empire of the Sun some 12 years ago. His estimation of the undertaking rises. I decide not to tell him that far from playing a child who salutes Allied warplanes as they take off to battle the Japanese, Bale is now cast as a misogynist murderer who mutilates his victims and revels in their blood and guts. I also choose not to try to explain that this film version of the Brett Easton Ellis novel American Psycho is intended as something of a comedy.

"I found the book funny," says director Mary Harron, whose debut feature I Shot Andy Warhol (1996) was a sympathetic portrait of Valerie Solanas, who attempted to assassinate the artist in 1968. Harron is sharing her dinner break at nearby Ruby Foo's Chinese restaurant with a couple of journalists. "It may divide that way: if you found the book funny, then you'll go for the movie. And it's also a period film. I would find it boring just to do a serial-killer film. I'm interested in individual lives against a social background, how people are affected by their time."

Harron, Bale and the film's publicists and producers are all keen to promote the book's humour and biting satire. But these are not the qualities that put it in the spotlight in the months preceding its 1991 publication. Originally it was to have been released by Simon & Schuster, but objections within the company sank the project. First the jacket designer bowed out, commenting, "I felt disgusted with myself for reading it." Further expressions of disdain came from sales and marketing staff. In November 1990 Simon & Schuster told Ellis he could keep his manuscript and his $300,000 advance. By the end of the month, however, Vintage Books, a branch of Random House, had picked up the rights. Within two months of the book hitting the shelves in April 1991 more than 100,000 copies had been sold.

Literary critics and feminist groups savaged the novel, and indeed it's difficult to imagine anyone reading American Psycho without being repulsed by the gratuitously detailed scenes of sex and violence. Patrick Bateman is a Wall Street broker who frequently ends his nights of expensive dining (in the script every restaurant is described as "insanely expensive"), drinking and snorting coke in nightclub toilet stalls with cold-hearted sexual encounters and vicious murders. He tortures many of his victims. At one point he induces a famished rat to enter a victim's vagina, where it feasts. Another time he has sex with a partner's severed head.

"I thought it was very violent, very disturbing," says Harron as she reflects on reading the book a number of years ago. "But I also thought it was a brilliant satire, and that none of the critics gave it credit for its portrait of the 80s and what you might call its 'incisive' look at male culture, the natural culture of Wall Street." The violence, perhaps inevitably, has been toned down for the movie. "I avoid the torture scenes," says Harron. "All that stuff with dead bodies, with rats. Just killing." She laughs self-consciously. "That's bad enough." But a look at the script shows that generous portions of murder and blood will still probably make it on to the screen - after all, this is why the public knows the book, and what it is likely to buy tickets to see.

"Bateman is a tragic monster," Harron continues. "But then he also represents the craziness of an era, all its psychoses wrapped up in one person - obsession with clothes, obsession with food, obsession with his skin. People said to me while I was writing it, 'Oh, shouldn't you say more about his childhood or his family?' But this isn't a psychological portrait. He's a symbol."

The film version of American Psycho has been an "impossible project" in Hollywood almost since the book was published. An army of writers, producers and directors have been attached to it at various times and even David Cronenberg had an unsuccessful stab at it. Harron came on to the project in 1996 and by spring 1998 her script was set to roll under the auspices of producer/distributor Lions Gate Films.

Enter Leonardo DiCaprio. In a press release it would later come to regret, Lions Gate announced at Cannes 1998 that DiCaprio had agreed to star in the film. "We're excited as hell!" president Jeff Sackman told me at the time, unconcerned that a $10 million project was about to balloon to $40 million - though given the sums offered Lions Gate by foreign distributors eager to cash in on the post-Titanic Leo craze, there seemed little reason to worry. But almost as soon as the story hit the trades in Cannes brickbats began to fly. Harron was off the project as she did not appear on DiCaprio's purported list of approved directors. Bale, obviously, was out too. Lions Gate, formerly the scrappy independent distributor Cinepix, which had been acquired six months earlier by Canadian giant Lions Gate Entertainment, was accused of betraying its indie roots. "There were so many things written that were inaccurate," complained Lions Gate co-president Mark Urman. "I'm sure it happens all the time, but in this case it bit us in the ass."

By the end of the summer DiCaprio had announced he wouldn't portray Bateman and Harron was called back. Now, a year later, all seems forgiven if not entirely forgotten. Mike Paseornek, one of the film's executive producers, praises Harron for her intelligence and understanding of the material, especially when she appeared on Canadian television to defend the film against a Toronto letter-writing campaign aimed at preventing filming there that included mothers of victims of a real-life serial killer who had kept American Psycho at his bedside. Nevertheless, Harron looks back on the DiCaprio imbroglio ruefully. "I learned a big lesson," she says. "You can work as hard as you like on something and then become dispensable if you don't go with a big star's programme. I'd been with the project for two years when it was halted - they didn't officially fire me, but when I said I didn't want to work with Leonardo that was it. And they never really talked to me again until they asked me back."

The request to return to the project came some three and a half months after the announcement that DiCaprio had agreed to star. "At first they said I could come back only if I didn't cast Christian," Harron recalls. "So they made some token offers to other actors, but a mainstream actor with his eye on a Tom Cruise-style career wasn't going to touch it." Bale, having passed up other films in the hope that American Psycho would work out for him, was happy to start. "Obviously I was furious about the move to cast DiCaprio," he said in his trailer during a break. "But it was a business decision. And one thing Mary has said to me is that at least Lions Gate has never tried to tell her how to make the film. No saying, 'Christian's got to be nicer. Why can't he be sympathetic?'"

On this Monday evening in mid April everyone on set is in a relaxed mood. There are only a few more days of shooting to go. The production is on time and within budget. The Toronto protests seem ancient history. Less than 24 hours later, however, two teenagers launch a gun assault on fellow pupils at their Colorado high school. A day later Universal announces it is pulling copies of Scott Kalvert's Basketball Diaries (1995) from video stores as it has been the target of criticism for a scene where DiCaprio fantasises bursting into a classroom and gunning down kids and teachers who've made his life miserable. Meanwhile Oliver Stone is in court defending Natural Born Killers against accusations by parents of the victims of a previous school rampage that the film was partially responsible for the actions of their children's killers.

"I guess it depends on whether people find the violence super-gratuitous," says Harron. "I don't think it is. People attack you for representing reprehensible behaviour as though you were glorifying it or condoning it. But I think there's something to be said about human cruelty. Somebody has to treat it at some level."

Brand names figure prominently in the novel, but many manufacturers have refused to allow their products to be used in the film. "Rolex said I could wear its watches as long as I wasn't killing anybody at the time," says Bale. "Maybe they were hoping to be featured - that every time Bateman kills, he takes off his watch." But Bale found the city traders the book satirises had no such qualms. "I chatted with a few of these guys when I was preparing for the role," he remembers. "For a lot of them, it's their favourite book. They just don't seem to get that it's laughing at them. And some really disturbing things came out of their mouths, referring to women as 'bitches' and 'cunts', for instance. When they were talking to me they seemed to assume I was the character. It was, 'Yeah, man! Bateman!'

"For me Bateman is a real dork," Bale continues. "You laugh at him, not with him. If you look at ads in GQ in the late 80s they're all like that - ridiculous Tom Cruise smiles. I even bleached my teeth for it. Bateman is very different from any character I've ever played because of how vacuous he is. His only self-awareness is a complete lack of self. So it's not like most films where people say dig deep for it, it's got to be real - here it's all about surface. Evil to me conjures up passion, whereas Bateman's vacuousness means he has no limits to what he can do because he feels no guilt. I've had a few people ask me how I can play this character without something of him lingering in myself. The answer is that it hasn't because it's such a pretence, even for him. I'm not trying to do a 'portrait of a serial killer' that displays why somebody kills. I think Ellis took clichés from serial killers and put them all together."

Harron, on the other hand, cannot always leave Bateman behind. "When the women are killed it's very upsetting," she says. "I had nightmares after shooting it. Next I think I'll do something lighter. It's been worthwhile, but it's hard to spend a lot of time in such a dark place."

Back on set Bale has just completed another take. The noise level begins to rise and residents are allowed to check their mailboxes. A long trail of smeared 'blood' shines crimson on the floor. As crew members set to work wiping it up and dragging the 'body bag' back to the starting point, a young girl, probably 11 or 12 years old, shyly approaches the actor. Bale takes her school notebook and engages her in light-hearted conversation as he signs his name. Five minutes later the American psycho is dragging his latest victim to the door.