Primary navigation

Stephen Soderbergh's up-down career defines the term maverick. But now, with his time-shuffle revenge movie The Limey following the success of Out of Sight, it seems he can do no wrong. Interview by Sheila Johnstone

When sex, lies and videotape won the Palme d'or in Cannes ten years ago, before making more than $100 million worldwide (on a budget of $1.2 million), Steven Soderbergh, then 26, became overnight the poster child of independent American cinema. The blockbuster event movies pioneered by George Lucas and Steven Spielberg in the mid 70s had dominated international markets for over a decade; Soderbergh's brilliant debut pointed to a different way forward. But then his next movies bombed: the angst-ridden Kafka (1991); King of the Hill (1993), the story of a small boy struggling to survive the Depression; the glacial film noir The Underneath (1995). Interviewed about the last, Soderbergh launched into a long, morose attack: "I've lost interest in the cinematic baggage you have to use to make a film palatable for a mass audience."

Unsurprisingly, his career went quiet. He took on a string of behind-the-scenes producing and script-writing assignments including Pleasantville and the ill-fated US remake of Night Watch. Plans for Quiz Show foundered when Robert Redford hijacked the project. Soderbergh the director appeared to be all washed up: a one-hit wonder.

In fact he had gone to ground to make Schizopolis, a no-budget, Dadaesque comedy in which Soderbergh himself plays the tragi-comic hero struggling with his sense of alienation and his failing marriage (his wife was played by the director's own soon-to-be ex-spouse Betsy Brantley). The film's reception at its Cannes premiere in 1996 was rather more muted than the ovation that had greeted sex, lies, with a torrent of bored and bewildered audience members diving for the exit. With his next film, Gray's Anatomy (1996), a small-scale piece made with the monologuist Spalding Gray, Soderbergh seemed to have disappeared for good beneath the radar.

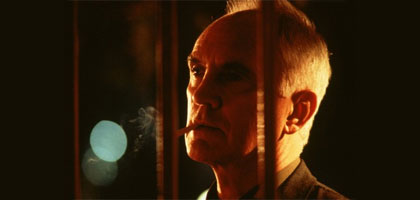

But then in 1998 he bounced back triumphantly with an unpromising-sounding assignment as director-for-hire on an adaptation of Elmore Leonard's novel Out of Sight, about a failed bank robber and a deputy federal marshall who can't decide whether to arrest the charming felon or fall in love with him. Sexy, elegant and profoundly romantic (a new departure for a director whose work has often been regarded as somewhat cerebral), it was hailed by critics as his best film since sex, lies. His return to favour continues with The Limey, which played out of competition at Cannes this year. The story of an English ex-convict (Terence Stamp) who travels to Los Angeles to investigate his daughter's death following her involvement with a hedonistic record producer (Peter Fonda), it is on one level a straight revenge thriller with strong echoes of Get Carter, while its spaced-out feel and bravura kaleidoscopic editing make it play like a homage to the formal experimentation of 60s and 70s cinema.

Soderbergh has been described by one US interviewer, a little patronisingly if not altogether inaccurately, as a "goofy, balding, loveable geek". But underneath that persona, thinly concealed, are a steely intelligence and formidable self-awareness. And though he has worked within an astonishing range of registers - from the avant-garde Schizopolis, through the quintessential US indie sensibility of sex, lies and the arty, black-and-white, middle-European universe of Kafka, to such demi-Hollywood genre pieces as Out of Sight and The Limey - he insists adamantly on the continuity of his work.

Sheila Johnston: You use a very complex chronological structure in 'The Limey' - was that written into the script or created at the editing stage?

Steven Soderbergh: I shot it that way. My whole line while we were making it was, "If we do our job right this is Get Carter as made by Alain Resnais," which I know spells big box office! I was trying to get a sense of how your mind sifts through things and I felt I could get away with a certain amount of abstraction because the backbone of the movie is so straight. Even so, my first version was so layered and deconstructed even people who had worked on the movie didn't understand it. So I had to start working back to find a balance, which I did through screenings for friends: writers, actors, producers, directors, a new group of guinea pigs each time. At one point Artisan [the production company] wanted a public preview. But I said, "For a movie like this it's worthless: it's going to score terribly and I'll get nothing I haven't already got by inviting intelligent, creative people to give me ideas." A week before we were going to do it, they called and said, "You're right, it's a waste of money. Just finish it the way you're going to finish it and we'll figure out the rest."

The film's steeped in the mood of the 60s, though you're a little young to have had much direct experience of that counterculture.

I've been working for some time on a book of interviews with Richard Lester called Getting Away With It and I asked him a lot about that period. Mostly we talked about the gradual shift from optimism to disillusion. I was whining about something and then I added, "Still, has there ever been a generation that hasn't said, 'It's never been this bad'?" He said, "Yeah, in the 60s." But as soon as it became apparent that the youth movement was an ongoing economic force, it began to be co-opted into mainstream culture, and that - combined with other things like harder drugs becoming available - was when things started to shift. When Lester made two trips to San Francisco to research and shoot Petulia in 1966 and 1967 he said he could feel a very strong, dark undercurrent on the second visit that wasn't there on the first. That's the feeling that permeates The Limey. There's one guy whose dreams of himself were lost in prison and another whose dreams were probably never even his own: he just took everybody else's and made money out of them.

How important was it to cast two icons of 60s cinema?

Both Terence Stamp and Peter Fonda have baggage that's not only specific to the 60s but has to do with a refusal to compromise: they've stayed pretty true to themselves all these years. But I wasn't trying to turn in a pastiche - though clearly when we had Peter Fonda driving in a fast vehicle up the coast, I thought, "We've gotta get Steppenwolf." Terence seemed like a Who kind of guy - in fact his brother, Chris Stamp, was one of the people who discovered them.

One of the film's most remarkable features is your use of scenes from Ken Loach's 1967 movie 'Poor Cow', in which Stamp played another thief, to show his character in flashback.

In cinema you can follow actors over a long period - you can really see the accumulation of someone's life experience. So the idea of using Ken's film was intriguing, and as far as I know no one had done that before. There was a lengthy process to get the rights because Poor Cow was based on a book by Nell Dunn, and Carol White, who was in the scenes we wanted to use, was dead. It went on for months and didn't get completely resolved until we were editing. Then I met with Ken and said, "Look, I've got this cleared up legally, but morally I can't do it if you think it's offensive." But when I explained what I was doing, he said it was fine.

When you took receipt of your Palme d'or for 'sex, lies and videotape' you said: "It's all downhill from here." Do you now feel that has been true of your career?

I was being facetious, but what I meant was that it seemed unlikely I would ever again be the recipient of such unified acclaim. A lot of people never are, and to get it for my first movie seemed almost comical. The Palme d'or helped me hugely - it made a name for me in Europe, where people sometimes like my movies more than they do in the States - but if sex, lies had made only half a million dollars nobody would be talking about it today. It was a modest piece with modest aspirations that happened to be what people wanted to see in a way I obviously haven't been able to duplicate. It was pure chance: I have a strong feeling that had it been made a year later it wouldn't have hit in the same way.

Unlike many younger American independent film-makers, you didn't use the success of your first film as a springboard to a commercial Hollywood career. Are you happy now with the choices you made?

Let's put it this way, I don't regret any of them. There have been good ones and bad ones, but I look back and think, "That's an eclectic group of movies that, for better or worse, belong to me." I turned down a lot of studio stuff - or rather traditional studio stuff, because two of my films were made by Universal - until Out of Sight, which seemed the perfect blend of what I do and the resources a studio can provide.

What is the difference between coming in on a pre-existing project and creating a film from scratch?

With a screenplay that didn't come from you, you get on that train and it takes a while to start driving it. But you work your way through each car until you get to the front, and once you're close to shooting there's really no difference. By then you usually have a healthy disrespect for - or sense of detachment from - the material, even if you've written it yourself. When we rehearsed Out of Sight I started cutting lines because, though Elmore Leonard writes great dialogue, it seemed in scenes like the last one there wasn't a lot to be said. That's one of the differences between a book and a movie. I met someone recently who was in Days of Heaven and she said there was lots of dialogue in the script, but when they got on the set Terrence Malick would go, "Don't say anything." When you look at the film you realise that he ended up having to write all that voiceover in post-production because nobody said anything so nobody knew what was going on! You think, "Oh, that's such a great example of stripping everything away," and then you find out why he did it. Sometimes it's better not to know too much.

Along with Barry Sonnenfeld's 'Get Shorty' and Quentin Tarantino's 'Jackie Brown', 'Out of Sight' ushered in a revival of interest in Elmore Leonard, whose work had rarely been successfully translated into film.

Quentin Tarantino's rise has so much to do with Elmore Leonard's world, as he would be the first to admit, that by the time a 'real' Leonard adaptation showed up in the form of Get Shorty, everyone had been prepared by Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction for that tone. Actually Get Shorty, Jackie Brown and Out of Sight are textbook examples of what a director does, because they all three feel like Elmore Leonard movies but are completely different from each other. When you try to explain what it is you do, this is it: you take a piece of material, it's filtered through your eyes and ears, and it comes out with a very specific atmosphere.

Your films have a lyrical, dreamlike quality that gives them an almost European flavour.

When I was at university I'd see one, sometimes two movies a night: films like 81/2 or The Third Man or A Hard Day's Night. I was drawn to European cinema - its approach to character was more complicated and stylistically it seemed more rigorous and interesting. When you see an Antonioni film at an impressionable age it has a huge impact. Everything on screen is there for a reason - even Zabriskie Point, which is odd and flawed, is astonishing to look at.

What's your prognosis for the new generation of US indie directors?

It's much harder for them today. The expectations are much higher and the competition is much fiercer. It's easier to get a film made now because sex, lies and a handful of others have made money. But it's much more difficult to get it released because the marketplace is very competitive and distributors are not as adventurous as they used to be.

What about your future plans?

I've just made Erin Brockovich, which is an aggressively linear reality-based drama about a twice-divorced mother-of-three living at a very low income level who talks herself into a job answering the phone and ends up putting together a case against a large California utility company that results in the biggest direct-action lawsuit settlement in history. She's played by Julia Roberts - if you're trying to sneak something under the wire, by which I mean an adult, intelligent film with no sequel potential, no merchandising, no high concept and no big hook, it's nice to have one of the world's most bankable stars sneaking under with you. Other than that, I'm riding off madly in all directions. I've always had one foot in and one foot out of Hollywood - that's what makes me comfortable. Together with Scott Frank, who adapted Out of Sight, I'm writing an original spec screenplay that's a multi-character murder mystery along the lines of an Agatha Christie. And I'm making notes for Son of Schizopolis - the sequel to the film nobody saw.