Primary navigation

Germany 1998

Reviewed by Richard Falcon

Our synopses give away the plot in full, including surprise twists.

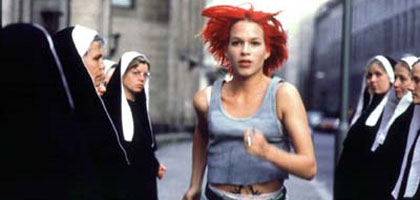

Berlin, 11.40 am. Young tearaway Lola receives a phone call from her petty-criminal boyfriend Manni. He has botched a diamond-smuggling job for homicidal gangster Ronnie, and left DM100,000 on a subway train where it was picked up by a tramp. If Lola doesn't get to him by 12 pm with a replacement sum, Ronnie will kill him. Lola runs to Manni and three contrasting narrative timelines follow.

In the first Lola sprints to the bank where her father is a director, only to interrupt her father's colleague and mistress Jutta Hansen's revelation that she is pregnant. The father turns on Lola, declares that she is not his daughter and throws her out. Lola runs to the phone box just in time to see Manni conducting an armed robbery at a nearby store. When she helps him, she is shot dead by the police.

In the second timeline Lola is tripped by a thug in the hallway. She arrives at the bank after Jutta has told her father that the baby isn't his. Lola robs the bank at gunpoint and escapes. As she arrives in time to prevent Manni from robbing the store, he is run over by a truck.

In the last timeline Lola runs to the bank but this time fails to cause a road accident which in the previous scenarios had prevented her father's colleague Meier from reaching the bank. She misses her father and he and Meier are involved in a road accident caused by Manni chasing the tramp. Lola gambles at a casino and wins the DM100,000. Meanwhile, Manni has recovered the money and given it to Ronnie. Lola and Manni are reunited.

Tom Tykwer's supercharged, exhilaratingly hyperactive movie had audiences in Germany and the US cheering at the screen. Emphasising emotional insecurity and cinematic style as did his earlier work, Run Lola Run sets new standards for the cinema of hysteria. It opens with a stylish sequence picking faces out of a crowd which later coalesce to form the title, and which - ironically - looks like a television commercial for insurance or financial services (heroine Lola runs each time to a bank). The voiceover suggests a copywriter's search for the meaning of life ("Who are we? Why do we believe?") but also offers us the answer courtesy of a comically gnomic quotation by Sepp Herberger, the legendary football coach who took Germany to victory in the 1954 World Cup: "The ball is round, the game lasts 90 minutes... everything else is theory."

Chaos theory in particular seems to be Tykwer's concern here, for the course of each of Lola's attempts to save her boyfriend Manni is determined by incidental micro-events - whether she is tripped on the stairs, if she causes a man to crash his car, and so on. But there is little of the romantic-comedy irony of Groundhog Day's repetitions or Sliding Doors' mirrored stories in the crisis that turns into three dramas for Lola. Nor is there an unwavering commitment to the existential crime-plot take on fate and chance that runs from Kubrick's The Killing (1956) to Tarantino. So many things have gone wrong by the time Lola receives her phone call - the theft of her moped, a taxi driver taking her to the wrong address in the east - that chaos seems the norm rather than a flaw in a masterplan. The only response is screaming, which Lola duly does, shattering glass like the dwarf Oskar Matzerath in The Tin Drum (1979), the benchmark German 'breakthrough film'.

With each repetition of Lola's itinerary we become more familiar with the elements of her environment, as with the levels of a computer game (the film uses a variety of mixed media - animation, video, 35mm stock as well as time-lapse effects and all manner of editing trickery). When Lola dies, she begins her quest afresh. And when she succeeds at the end, we feel, irrationally, that she has earned this for her exertions over the three mutually exclusive stories, none of which is more real than any other. This meticulous representation of chaos is clearest in the asides in which the lifelines of incidental characters flash by in seconds. The extreme alternatives here include car crashes, child kidnapping, unforeseen meetings leading to marriage or sadomasochistic relationships, lottery wins and more. On one level this is slapstick (Tykwer cannot resist showing us the ambulance crashing through the plate glass it narrowly avoided the first time around). But it is also the logic of interactive DVD and of gamesplaying where each decision has potentially disastrous but never mundane results.

With a Hollywood remake likely, Lola may, of course, be transformed into a Lara Croft-style digital heroine. What will be lost then, though, is extremely old-fashioned and precisely what makes Run Lola Run great: for all its Teutonic version of cinéma du look stylisation, pop-video aesthetics and pumping techno which keeps us breathless, we empathise with Lola, whose lover's pillow talk with Manni about love and death links the three narrative strands. That Tykwer maintains our flow of empathy while demonstrating and exploiting the potential of interactive cinema manqué is, in itself, an awesome achievement.