Primary navigation

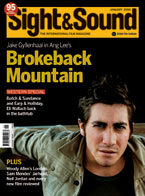

Western special: Brokeback Mountain has been described as "one of the greatest cinematic love stories of all time" and has been lauded for "queering the Western". With director Ang Lee making yet another genre his own and with Jake Gyllenhaal and Heath Ledger performing prodigiously, what better excuse is there for a return to the high country? By Roger Clarke

Gay cowboys? The last time they caused such a ruckus was in the late 1970s when the Sex Pistols played Randy's Rodeo at San Antonio in front of two thousand boozing rednecks. Sid Vicious sported a Vivienne Westwood Seditionaries T-shirt for the occasion: two cowboys with no trousers getting very well acquainted (actually in a bored kind of way, though it doesn't appear so at first glance). It's safe to say that the audience's riders of the purple sage didn't much appreciate the gesture, which in the traditional all-male cowboy milieu was perhaps a little too close to the bone. They still don't care for any such suggestion, but Ang Lee has made a film about cowboys in love just the same. Brokeback Mountain won the Golden Lion at Venice in 2005, where jury member Claire Denis could perhaps see reflected her own homoerotic Foreign Legion film Beau Travail rather than Wanderer of the West (1927), say, with its stock sissy foil designed to enhance the masculinity of the other men.

Brokeback Mountain is the story of two tall and athletic young cowboys, dirt poor, who become lovers during a season working alone together in deepest Wyoming in 1963. Ennis Del Mar (Heath Ledger) and Jack Twist (Jake Gyllenhaal) have a brief and impassioned affair that seems to melt like the mountain snows once they return to the lowlands. But over the next few decades, despite marriages and children for both of them, their connection keeps coming back, with fishing trips their excuse to get away together from family lives that seem far from happy. Ang Lee, returning to themes he first explored in The Wedding Banquet, has specifically denied that his film is a gay Western. "For me it's a love story," he told the LA Times in early November. "It has very little to do with the Western genre."

Ang Lee is no longer just an indie director but is the man who made the 2003 blockbuster Hulk. And the 'gay thing' has always been a problem in mainstream movies (Brokeback Mountain, made by James Schamus for Focus Features, comes under the Universal umbrella). It is said that in 1982 the producers of the Sidney Lumet thriller Deathtrap calculated that the screen kiss between Michael Caine and Christopher Reeve shaved $10 million off their profits, though these days a smooch between Val Kilmer and Robert Downey Jr in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang is merely the subject of amused arts-page editorials, requiring a slight adjustment in studio marketing tactics - even if director Shane Black owns up to a moderate case of nerves when it came to writing in a sympathetic gay character.

Meanwhile in redneck country little has changed since the Sex Pistols concert ended in a near-riot, and Brokeback Mountain, lauded by some as one of the greatest cinematic love stories ever made, is unlikely to appeal to most saddled-up whipcrack-away Texans. It probably won't be screened at the well-upholstered private cinema in the White House, while in Florida Jeb Bush will pass a law against it if he possibly can: Ang Lee has chosen to mess with Texas and that's something we're not supposed to do.

It has taken a heterosexual Taiwanese director (Lee is married with two sons) and heterosexual Australian and Californian actors to ride with gay cowboys and not make it feel like a parody. ("I really didn't want it to be Blazing Saddles," Lee told me when I mentioned I thought the first internet reports of the film were a spoof.) The New Queer Cinema hipsters never did deliver a simple and true gay love story, or one as honeyed and bitter as this. Indeed, Brokeback Mountain - self-consciously archaic and arcadian and painted on a grand canvas - is the antithesis of that urban film-school movement. B. Ruby Rich, who did so much to identify New Queer Cinema in the 1990s, has praised it as the gay breakthrough film that was never delivered by the likes of Gregg Araki or Todd Haynes. "With utter audacity," writes Rich, "Ang Lee... has taken on the most sacred of American genres, the Western, and queered it."

Rich warns against the excessive reinterpretation of genre classics in the light of Brokeback Mountain - despite her claim that it "virtually queers the Wyoming landscape as a space of homosexual desire and fulfilment." But surely cowboy flicks were always a tad gay, or at the very least homosocial (a term Atom Egoyan uses of his latest film Where the Truth Lies and of the Ratpack activities in the late 1950s). Westerns exist mostly in a semi-adolescent male world, with the great dusty plains and heaving flanks of cattle acting as the US equivalent of Britain's boys' boarding schools. The genre was always about men getting it on (or squabbling) with other men, which is why the overtly gay cowboy film remains possibly the last Hollywood taboo.

By the same token women have often been presented as a problem by the makers of Westerns - daughters to be disciplined, hoydens, harridans and whores to be avoided, mothers to be feared as they doggedly brush the porch or cook up beans (strong women like Joan Crawford in 1954's Johnny Guitar seem a kind of freak show). Men, as Alex Cox has noted, make and own the Western, "which is what makes Westerns such tremendous fun for boys and so boring for women."

Brokeback Mountain breaks new ground here too, for Ang Lee gives his female characters a rich texture. These women are not necessarily sympathetic but they do seem real - as in the scene where Jack's wife Lureen (Anne Hathaway) makes a final phone-call to Ennis, the rage of love and hate on her face providing one of the film's most startling and affecting moments. Yet these women also trap their men in domesticity: the noise of the Laundromat above which Ennis lives with his wife and squalling daughters is in direct contrast to the natural sounds of the wilderness in his scenes with Jack; the chug of the company adding machine and combine harvesters of Jack's life (he has married into a prosperous farm-machinery family) only adds to his sense of suffocation. There are two significant Thanksgiving scenes where the carving of the turkey is interrupted by the sound of the television or of a newfangled electric carver.

Lee photographs the scenes where Jack and Ennis first work together in mountain peaks that are accessible only by mule with considerable attention, relating the landscape to the men in a much more subtle way than John Ford achieved with all those phallic buttes in Monument Valley. He says he had the spare guitar chords of the score in his head even when he was scouting for locations. As he fleshes out the men's relationship - one tending the camp and the other high on the peak guarding the sheep from coyotes - he suggests that Jack may be the proactive partner and Ennis the homely sensible one, confounding the eventual configuration of the only full sex scene, after whisky has been consumed and the night is sufficiently cold. To use the later, unexpectedly beautiful phrase of their contemptuous employer, this is the moment when they "stem the rose".

That the men are tending sheep is perhaps already a signal that we are stepping away from the traditional cowhand aesthetic: this could be Palestine in Biblical times or Greece when the gods walked the earth (Ganymede, after all, was a shepherd) if it weren't that the hills, forests and skies of Wyoming are so particular. There's even a muted hint of the early scene of sheep running off a cliff in John Schlesinger's 1967 Far from the Madding Crowd (jumping off cliffs naked together on their fishing trips is one of the men's especial pleasures). Shepherds are perhaps more intimately involved with their animals than other farm workers and here the ministrations to the diminutive sheep and lambs are shown as almost maternal.

Universality and timelessness make Brokeback Mountain feel as if its story could have happened anywhere around the world in any era since the bronze age (confirming Lee's contention that it is not in fact a Western). It takes place over 40 years beginning in 1963, a few months before the assassination of John F. Kennedy, but nothing about America registers in the narrative. Vietnam? No mention. The Summer of Love? Nothing there. There's no Scorsese-like time-setting music, and Nixon, Wall Street, Robert Mapplethorpe or Bill Gates might as well not exist. The only sense of time passing is in the upgrades of the pick-up trucks, occasional period interiors or a new windcheater or jacket. Mechanisation is routinely shown as alien and alienating and the two main characters' fishing trips seem to be as much about getting away from the world as about evading their wives. Only when Ennis brings his two daughters to their trysting place does the idyll collapse once and for all.

Brokeback Mountain is adapted from a short story by Annie E. Proulx (author of The Shipping News) which originally appeared in the New Yorker in 1997. A year later a gay 22-year-old University of Wyoming student named Matthew Shepherd was lynched, an incident that has been the subject of a brace of television biopics including HBO's The Laramie Project starring Christina Ricci, Laura Linney, Steve Buscemi and Peter Fonda. It's hard not to read this hate-crime as being referenced in Brokeback Mountain through the flashbacks when Ennis recalls his gloating father showing him the brutalised bodies of two lynched gay men.

When I met Lee in London during his promotion of the film he emphasised the strong effect Proulx's story had on him and said he was especially drawn to the wordlessness of the men's relationship, "something I originally thought was down to the writer, but found to be true among men of this kind." One could even make a case that the film draws not so much on the Western as on the cult of Walt Whitman - a poet who celebrated a muscular, nature-suffused love between men - which influenced the likes of Allen Ginsberg, who in turn filtered its poetic torrent through the persona of Jack Kerouac. Yet Westerns too have a tradition of gay subtexts: think of Montgomery Clift in Red River (1947), the marauding cowboy gang with its predilection for male rape in Giulio Questi's Texmex hallucination Django Kill (1967) or James Dean in Giant (1956), sporting a look that anticipates Jon Voight in Midnight Cowboy (1969), Schlesinger's sensitively calibrated account of unconventional male friendship and a hustler dressed in cowboy duds. And there's no denying that Andy Warhol (or his directorial representative Paul Morrissey) knew exactly what he was doing when he shot the subversive and fetishistic Lonesome Cowboys (1968) in Oracle, Arizona, on sets that had been used in Westerns for over 30 years, incurring the wrath of both locals and tourists. (The film remains banned in the UK.)

Lee denies he had any movie in mind apart from Peter Bogdanovich's The Last Picture Show (1971), and that film's Texan screenwriter Larry McMurtry also scripted Brokeback Mountain. It has been claimed that Bogdanovich's then-lover Polly Platt was an important influence in the film's gauging of the love between two men, and in some ways The Last Picture Show anticipates the multiple lenses of male and female subjectivity in Brokeback Mountain. Is Lee's sensitivity towards his gay characters here and in The Wedding Banquet all down to his much-lauded ability to 'seduce' a good performance from his actors? "I can really identify with being gay," he tells me, "because I identify with being the outsider." In fact, he himself points to gay themes in a surprising range of his films: "Ride with the Devil is so homo you just can't help it," he laughs. "In the Civil War all these men slept together like spoons in the drawer. And the Hulk fighting with his father is very homo - it reminds me of some moments in the films of Tsai Ming-Liang."

I observe that all the computer-generated Hulk sequences were based on Lee himself, performing the actions before a camera that captured his movements and incorporated them into a CGI programme, and that battles with patriarchs are another of his recurrent themes (both Ennis and Jake admit to being under-fathered). Does he ever question his identification with gay men? "I don't know," he says shyly. "Like the actors, I try not to think too much about it."