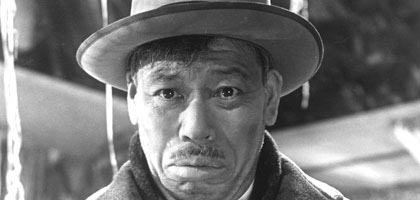

Shimura Takashi: The Last Samurai

The Actors: An underrated figure continues our series on performers. Long in the shadow of the mercurial Mifune, Kurosawa's other favourite, Shimura, embodied all the traditional virtues of restraint in Japanese cinema. By Alex Cox

Kurosawa told stories of individuals who stand out from or oppose the group. Drunken Angel is the tale of two such characters: the alcoholic yet heroic Doctor Sanada and the gangster Matsunaga, who discovers he has TB. "Shimura played the doctor beautifully," the director said, "but I found Icould not control Mifune." So while Shimura stuck to the script, Kurosawa - despite his reputation for discipline - had to let Mifune do as he wished. The decent if flawed Doctor Sanada was meant to be the hero, but thanks to Mifune's intense performance it is Matsunaga who dominates.

Drunken Angel's popularity seems to have been attributed to Mifune and he received top billing when the two were paired again a year later in Kurosawa's The Quiet Duel and Stray Dog. In The Quiet Duel both actors are doctors and Shimura plays Mifune's father, but Stray Dog, in which the two are detectives, is the more interesting film. Mifune is a nervous rookie who has lost his gun and Shimura the older, wiser officer who reassures him. Again Mifune has the showier part - he is almost as psychotic at times as the killer who has his gun - but Shimura has a moment that both defines and jokes with his father-figure stereotype. The search for the killer leads the pair to the most impoverished part of Tokyo. At the end of a montage Shimura leads Mifune into a deserted yard where the young cop (and the audience) anticipate the killer will be hiding. Instead, Shimura's children appear, shouting: "Welcome home, daddy!" Without telling him, Shimura has brought his colleague home for supper.

The upright family man is not the only character in Shimura's repertoire, however. In 1950 he played the corrupt lawyer Hiruta in Scandal,Kurosawa's flawed film on the theme of the fragile privacy of celebrities. From the moment he appears, Shimura dominates the film, and indeed Hiruta is its only interesting character: by turns wheedling, aggressive, cowardly and confused, he is redeemed by his sincere love for his sick daughter, and his breakdown in the long courtroom scene is marvellously performed. Mifune, as the painter Aoye, is out-acted for a change.

In the same year Shimura appeared as the unreliable narrator and woodcutter in Rashomon, the film that brought Kurosawa and Mifune (who gave the stand-out performance) to international attention when it was awarded first prize at the Venice film festival. The following year Kurosawa again gave Shimura a supporting role, as the heroine's father in his version of Dostoyevsky's The Idiot. Then in 1952 the director cast the actor in Ikuru as Watanabe, the bureaucrat who learns he is doomed to die of cancer. Watanabe is a version of Hiruta - more repressed, more beaten-down, more useless - yet he achieves something of lasting value when he champions the creation of a children's park on a swamp earmarked by gangsters for construction. Shimura brings to the character the persistence and perseverance of his samurai: when he accepts that he is dying, like a samurai he becomes fearless, yet there is no bravura or excess. Shimura portrays perfectly the mediocre man who dedicates himself to a single action.

Watanabe is the most complex of Kurosawa's triumphant individualists - the only bureaucrat in his division ever to have stepped out of line or achieved anything - and it's hard to imagine any actor giving a more restrained or sympathetic performance. Yet Kurosawa claimed to be dissatisfied: "[Shimura's] image of Watanabe was not the same as mine. He played the part with all stops out, and I would have preferred something a bit more relaxed… Shimura is the kind of man who is always making things difficult for himself and so he strains too much."

1954 saw Shimura appear in both Gojira (aka Godzilla) and Seven Samurai. Gojira was intended by its director Honda Inoshiro as an environmentalist horror film. Honda and Kurosawa had worked as assistant directors together and Honda was keen to have Shimura play Doctor Yamane, the only memorable human character in the film. (Shimura reprised the role the following year in the first sequel, Gojira No Gyakashu.)

The role of Kambei in the epic battle picture Seven Samurai is Shimura's most significant piece of work after Watanabe. Kambei is the group's leader, another heroic, militaristic father-figure, and it is Shimura, not Mifune, who got top billing. Kambei is a magnetic character who can convince other masterless samurai to follow him even into a doomed and unrewarding fight. Like the hapless Watanabe, he keeps the thought of death in front of him at all times - part of the samurai code of bushido - and fearlessly does what's right. Despite the samurai's noble status, Kambei allows Mifune's character Kikuchiyo - a commoner - to join his band. Shimura's ability to be still and to convey patient concentration distinguishes him from the excess of most of the other actors and it's fascinating to watch the scenes featuring both Kambei and Kikuchiyo, with Shimura's restraint working in contrast to Mifune's ebullience.

Kurosawa returned to fearful and equivocal characters with I Live in Fear (1955), in which Mifune plays an old man terrified by the prospect of nuclear war whose family seeks to have him declared of unsound mind, and Shimura plays Doctor Harada, a voluntary member of the family court who has grave doubts about their actions. It marked the start of a series of smaller roles, often as a villain, for Kurosawa: Shimura appeared in Throne of Blood (1957), a version of Shakespeare's Macbeth; as an elderly general in The Hidden Fortress (1958); as a mafia boss against whom Mifune's character swears revenge in The Bad Sleep Well (1960); and as the callous, cowardly leader of one of two warring gangster clans in Yojimbo (1961).

In both Ikiru and The Hidden Fortress Shimura provides natural and credible portrayals of characters much older than himself, despite an absence of make-up. By contrast, when Mifune plays the elderly protagonist of I Live in Fear he is layered with 'old man' lines that only draw attention to an already unconvincing performance. Mifune was a great actor who could do one thing very well; Shimura was a great actor whose versatility was seemingly limitless.

Shimura continued to play supporting roles for Kurosawa in Sanjuro (1962), High and Low (1963) and Red Beard (1965), an epic about a medieval doctor who was played by Mifune. In 1964 he also starred as a priest in Kwaidan, a horror film directed by Kobayashi Masaki. After Red Beard Kurosawa and Mifune fell out: Mifune was reported to have grown tired of the difficult director. And after the disaster of Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970), from which he was fired by 20th Century Fox, Kurosawa broke with most of his other actors. But Shimura had continued to work with other directors and remained a stalwart of samurai films and Toho monster films - in which he usually played a scientist, good or evil - including Honda's Mothra (1961), Ghidora, The Three Headed Monster (1964) and Frankenstein Conquers the World (1965).

He retired from acting in 1978 but two years later Kurosawa persuaded him to appear in a new epic samurai film Kagemusha, part-funded by Fox, who agreed to the deal under pressure from George Lucas. Donning his armour for the last time, Shimura played the warlord Taguchi, but the US producers cut his scenes. (They have been restored in certain DVD versions.) He died in Tokyo in 1982.

In Donald Richie's book The Films of Akira Kurosawa Shimura speaks briefly about the director for whom he did his greatest work. "Kurosawa never tells an actor how a thing should be done. Rather, he looks at the actor's interpretation and may then make suggestions such as: 'I don't think that's quite enough' or 'How would this way be?' or 'Perhaps we'd better not do that'." A hands-off approach from a famously exigent director suggests enormous respect for the actor: respect that was reciprocated and well deserved.