Primary navigation

Ali Jaafar views terror and war subjects

Midway through this year's festival, Oliver Stone flew in to introduce a 20-minute preview of his forthcoming 9/11 film ' World Trade Center'. "The truth must exist in some way to confront power and extremism," the combative director told a packed house. While it was difficult to judge the final film from what was essentially an extended trailer, the experience of being inside the Twin Towers was genuinely disquieting and the final image of two eyes peering through the dust-filled darkness drew enthusiastic applause.

Power and extremism proved to be recurring themes, with Bruno Dumont's 'Flandres', Rachid Bouchareb's 'Days of Glory' ('Indigènes') and Alejandro González Iñárritu's 'Babel' all addressing the clash between east and west. Rabah Ameur-Zaimeche's 'Bled Number One', playing in Un Certain Regard, tells the story of Kamel, an Algerian recently freed from a French prison and deported to his home village. Tackling issues such as Islamic fundamentalism and women's rights, the film succeeds best when capturing the horrifying brutality of gangs of misguided youths intent on enforcing their own moral order.

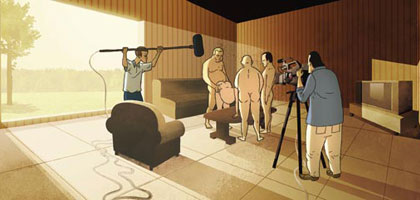

Perverted morality also pervades Anders Morgenthaler's 'Princess', which opened Directors' Fortnight. Mixing live action with blood-soiled animation, it follows guilt-ridden clergyman August's attempts to avenge the death of his porn-star sister Princess and protect his five-year-old niece. Including an animated gangbang and a scene where a little girl cracks open an obese pornographer's skull with a club, Morgenthaler's film is enjoyably deranged and undeniably challenging.

Far less controversial is Michel Ocelot's 'Azur et Asmar', also playing in Directors' Fortnight. Telling the story of childhood friends turned foes - blue-eyed boy Azur and his Arab nurse's son Asmar - the film is a beautifully animated tale of redemption in a world of clashing civilisations. One of its Cannes screenings was attended by a group of enrapt children, perhaps a more trustworthy indication of its quality than the gaggle of bleary-eyed critics.

Egyptian cinema marked a return to form with out-of-competition screenings of 'These Girls' ('El-Banate Dol'), a documentary about Cairo teenagers, and 'The Yacoubian Building' ('Omaret Yacoubian'), based on Alaa Al Aswani's blockbuster novel. In a bold attempt to portray the kaleidoscope of modern-day Cairo, debut director Marwan Hamed reminds viewers of a time when Jews, Christians, Muslims and whisky mixed freely, before daring to ask what went wrong.

Less successful is Israeli Udi Aloni's 'Forgiveness' ('Mechilot'), which seems to locate the key to Israeli-Palestinian peace in taking ecstasy and dancing round nightclubs in wet

T-shirts. Also disappointing was 'Halim', an attempt to dramatise the life of popular singer Abdel Halim Hafez.

Its star Ahmed Zaki, the best Arab actor of his generation, was diagnosed with cancer and died during filming, leaving his son to take over the role.

'How Are Things?' ('Keif al-Hal'), which had is premiere in the market, is the first full-length Saudi feature, a domestic drama tracing the struggle between the forces of modernity and fundamentalism. Cinemas are still banned in Saudi Arabia, but it was encouraging to find new territories being discovered at Cannes.