Primary navigation

Hou Hsiao-Hsien may be a long-established name to the cognoscenti, but his work is still little known in the UK. Three Times, his exquisite new tripartite film, is about to change all that. By Tony Rayns

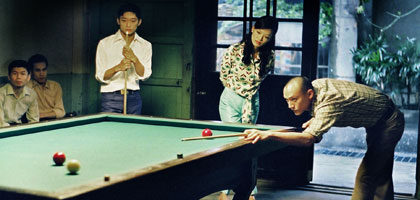

You don't need to watch much of Three Times (Zui Hao de Shiguang) to see why it's getting wider international distribution than most of Hou Hsiao-Hsien's other movies put together. A few main credits appear in stern silence, but image and sound soon fade up together. The first image is of an old-style tin lampshade; the camera drifts down to the green baize pool table below and then glides back and forth (there is minimal cutting, and just one elegant shift of focus) to follow two young men playing a game, watched by a young woman whose responses seem a little forced. On the soundtrack are the Platters, singing Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.

A superimposed caption identifies this scene as taking place in 1966 in Kaohsiung (Taiwan's large southern port), but it could be more or less anywhere in the 'developed' - Americanised - world in the era after World War II. For baby-boomers of both sexes, this is an archetypal adolescent memory: the moment when romance and sex suddenly arrived at the top of the agenda and the lyrics of pop songs began to sound relevant to your life.

Like all truly universal scenes in movies, this one is full of very specific details: the clothes, the haircuts (one boy is close-cropped, signifying that he's doing his military service), the decrepit building's Japanese-style sliding doors. But it's the sensuality that really gets you. The relaxed precision of Mark Lee's camerawork marries with the familiar song to create pure cinematic dulce de leche, while the casting raises the romantic temperature by a factor of ten. The boy with cropped hair is Chang Chen, the most in-demand Chinese actor of the moment, here trying to impress the young woman with a display of studied indifference. His pool-playing friend is guest star Ke Yulun; both boys made their screen debuts as teenagers in Edward Yang's A Brighter Summer Day (a seminal account of Taipei's teen-gang culture of the 1960s) and went on to appear together in Yang's dark comedy Mahjong, and their reunion here evokes warm memories of those films. And the woman is Shu Qi, the former Taiwanese starlet who proved her versatility as a jobbing actress in the declining Hong Kong film industry of the 1990s and established herself as a major talent in Hou Hsiao-Hsien's Millennium Mambo (Qianxi Manbo, 2001). The scene fades to black on a shot of her watching the game, poised between professional detachment (she works in the pool hall) and half-interested awareness that a shy flirtation is in progress.

Romantically speaking, very little happens in this first chapter of Three Times, which is titled 'A Time for Love'. During his one-day furloughs, the boy chases the elusive girl across the island from one pool hall to the next; they eventually meet for a chaste few hours between the time she finishes work and the time he catches the early bus back to army camp. The effect, though, is disproportionately potent. The chapter is up there with the best of Wong Kar-Wai as an intense affirmation of adolescent emotions: it feels good in a way the contrivances of Hollywood 'feelgood' movies rarely do.

The other two chapters of the film offer very different accounts of love at two other moments in Taiwan's history: 1911 and 2005. All three chapters feature the same cast, not to suggest reincarnations but to accentuate the contrasts. The 1911 chapter 'A Time for Freedom' is presented as a silent movie with music (the dialogue appears on inter-titles) and set in a 'flower house' where gentlemen callers are entertained. Seeing a pregnant younger colleague hastily married off, a courtesan begins to feel that she's 'on the shelf' and pines for a real relationship with her regular client. But he is working for Sun Yat-Sen's imminent overthrow of imperial rule in China, and shuttles between Taiwan and Japan (Taiwan being a Japanese colony at the time) raising funds for the revolution; he is too preoccupied to bother with her dreams, though the poem he sends her in a letter seems to carry an undertow of personal regret.

'A Time for Youth', the 2005 chapter, is set in Taipei, and Shu Qi's character is based on the real-life rock singer Oy Gin, who used to publish a startlingly frank blog about her bisexual affairs and health problems. Here the issue is whether or not the woman's fling with a professional photographer will lead to anything more lasting, and end her relationship with her current, argumentative girlfriend. The chapter is intricately structured and studded with telling details, but it's centrally about aimlessness and lack of commitment. It forms a diptych, incidentally, with the feature Reflections (Ailisi de Jingzi, 2005), produced by Hou and written, directed and photographed by his long-time assistant Yao Hung-I, which stars Oy Gin herself in a quite similar fiction also inspired by her blog.

This is not the first time that Hou has built a film on comparing and contrasting the manners and mores of different periods: Good Men, Good Women (Hao Nan Hao Nü, 1995) cuts between a grungy, violent and guilt-ridden present and the no more idealised 1940s, when Taiwanese left-wing intellectuals went to China to help fight the Japanese only to face anti-communist persecution back in the Taiwan of the 1950s. But that was Hou's most structurally complicated film, and it proved to be beyond the comprehension of most audiences, east and west. Three Times, on the other hand, is highly accessible. It has stars, it deals with romance and it features a lot of music. Happily, it's also a film that justifies Hou's consistent ranking in international polls of 'serious' film critics. For the first time in more than 15 years (I'm excepting the remarkable box office for Flowers of Shanghai in France), Hou's critical standing is being matched by popular success.

It's an interesting and surprising turn of events, since Three Times is in no fundamental way different from other recent Hou Hsiao-Hsien movies. In fact, it's a kind of summation of his work to date, its three chapters corresponding neatly with the three overlapping phases of his film-making career. Like Café Lumière (Coffee Jikou, 2003), it's organised around a set of motifs rather than any conventional dramatic structure. The threads that link the chapters include letters (replaced in 2005 by text messages, obviously), poems and song lyrics, journeys and inarticulate lovers. Hou is fascinated by the changes time wreaks - the steady erosion of formality in courtship, the endless reinvention of manners and body language, shifting fashions in popular music - but also by the underlying similarity of the chapters. Insofar as they tell stories, all three show how their characters' actions and attitudes are shaped and circumscribed by social and economic factors. Some things never change.

There's nothing remotely Bressonian about Hou's style of film-making these days, but he does share two important characteristics with the late French master. First, in shooting and editing his films he pares away the inessential to leave kernels of information that are key to the understanding of the characters and their circumstances. There's no showing-off, nothing self-consciously 'stylish'. Second, he never tells the viewer what to think: the approach is unassertively observational and seemingly uninflected, designed to give audiences the space and time to figure out what's going on and what larger meaning it might have. Hou's films weren't always like this, of course. His first three features (1980-82) were largely unambitious vehicles for pop stars of the day, filled with the kind of wholesome, socially improving 'messages' that the Kuomintang government expected from Taiwan-based artists at the time. Watching the 'real' Hou Hsiao-Hsien emerge from such negligible beginnings has been one of the greatest delights in the last quarter-century of cinema.

Hou was born into a large Hakka family (five kids) in southern China in 1947. His father was tubercular and moved to Taiwan for the sake of his health soon after Hsiao-Hsien was born; the family followed a year later. Like most mainlanders who moved to the island, they didn't expect to stay long; they furnished their house in Fengshan, just outside Kaohsiung, with cheap cane furniture that could be dumped when they returned to China. Hou grew up a semi-delinquent teenager (the gang culture described in A Brighter Summer Day was impossible to avoid) but also loved going to the movies. He once told me (the interview was published in the Monthly Film Bulletin, June 1988) that it was seeing a British movie starring Judy Geeson that made him resolve to become a film-maker: "I went home and wrote that in my diary." And so he went from his compulsory military service into the film department of the National Arts Academy at the age of 22. He was a movie fan but in no sense a movie brat: there was no access to 'great cinema' in the Taiwan of the 1960s and 1970s.

Nobody, including Hou himself, has ever fully explained what made this unformed young man reject the ideas and working practices of the industry that trained him and look for his own way forward. I guess we have to call it talent. In 1983 the government-owned Central Motion Picture Corporation (initially founded to produce anti-communist propaganda movies) was casting around for ways to revitalise Taiwan's dismal film culture. Two writers in the script department pushed the idea of portmanteau features, each with three or four episodes by young directors. Hou, fresh from the early pop-star vehicles, contributed to this project by directing the title episode of The Sandwich Man (Erzi de Da Wan'ou, 1983), based on a short story by then-fashionable 'nativist' writer Huang Chunming. It's about an impoverished young man who tries to support his wife and child by dressing as a clown to promote a failing local movie theatre. Hou delivers a solid neorealist piece, rooted in a rather facile irony and full of the kind of emotional manipulation his later films would avoid. None the less, this was his first 'serious' film and it changed the course of his career.

Even if Hou hadn't admitted it, it would be easy to guess that the first episode of Three Times is autobiographical. "Before I went for my military service," he told me when I asked him some questions for the film's press-kit, "I used to chase the so-called 'pool-girls' around the pool halls." Autobiography turned out to be the catalyst for the first phase in Hou's reinvention of his own film-making. His first indie feature The Boys from Fengkuei (Fenggui Lai de Ren, 1983) is his equivalent of Fellini's I vitelloni (1953), a group portrait of four laddish adolescents on the razzle in Kaohsiung as they approach the onset of adult life; Hou gives himself a cameo as a brash wideboy to underline his closeness to the characters. He followed this with A Summer at Grandpa's (Dongdong de Jiaqi, 1984), drawn from one of his regular screenwriter Chu Tien-Wen's childhood memories. (She is one of Taiwan's most distinguished novelists.)

And then came the overtly autobiographical The Time to Live and the Time to Die (Tongnian Wangshi, 1985), chronicling the Hou family from 1957 to 1966 and seeing them as representative of all mainland 'immigrants' in Taiwan, and Dust in the Wind (Lianlian Feng Chen, 1986), based on writer Wu Nianzhen's memory of being jilted by his childhood sweetheart while he was away doing military service. Hou says he was emboldened to turn such memories into films by reading the autobiography of the Hunan writer Shen Congwen. He especially liked the book's objectivity in describing traumatic times and events.

It's not much of a stretch from thinking about the implications and resonances of personal life-stories to thinking about the history of the place where they're embedded, and the next phase in Hou's creative evolution did just that. (The 1911 episode in Three Times looks back at - and in some way sums up - that phase.) It began with his 1989 Venice Golden Lion winner A City of Sadness (Beiqing Chengshi), which breached a longstanding political taboo by discussing the Kuomintang's massacre of non-violent street protestors in Taipei in 1947; it was a sad irony that the film was completed and premiered less than three months after the Tiananmen Square massacre in China. The film charts the experiences of one large family between 1945 and 1947 (it opens with the broadcast of Hirohito's famous surrender to MacArthur and goes on to show the exodus of the last Japanese settlers from Taiwan). The massacre itself takes place offscreen, but the political stresses that provoked it are illuminated in a series of scenes in which a group of Taiwanese intellectuals meet to drink and talk.

Hou explored Taiwan's extraordinary 20th-century history further in The Puppetmaster (Xi Meng Rensheng, 1993), which looks at the decades of Japanese colonial rule, and Good Men, Good Women, which, as we've already noted, re-examines the fate of Taiwan's leftist intellectuals in the war and post-war years. Both films were based on autobiographical accounts of the periods they describe, the first on traditional puppeteer Li Tianlu's memories of life under the Japanese, the second on a play by the woman protagonist Chiang Biyu; Hou clearly needs the prism of a first-hand account to help him engage with larger political and social issues.

That's no surprise, given the complexity of Taiwan's history. There has been a Chinese presence on the island for many centuries (members of the aboriginal tribes who were there first survive as labourers, sex-workers and performers in theme parks), but there was little sense of unity with mainland China. The Japanese occupation (1895-1945) was widely welcomed: the Japanese brought schools and hospitals and built roads and railways, and many Taiwanese of the pre-war generation came to think of themselves as more Japanese than Chinese. Conversely the arrival of Kuomintang (Nationalist) administrators in 1945, followed by the flood of economic migrants from the mainland that included Hou's family, provoked a new sense of Taiwanese identity that exists to this day. And when Chiang Kai-Shek and the Kuomintang government arrived in 1949, driven out of China by the communists and backed up by the US military, chasms opened up in the island's social fabric - most of which remain unbridged, even now that the Taiwanese dialect Minnan-hua has replaced Mandarin as the island's lingua franca.

The fact that viewers need at least a sketchy grasp of this history to make sense of Hou's 'history' films has obviously limited their commercial potential, but so have his increasingly refined experiments with film form. The Puppetmaster, for instance, is framed almost entirely in long-take, fixed-angle tableaux, staged in depth and exquisitely composed; they give the film a hypnotic, dreamlike tone (the Chinese title means 'Theatre, Dream, Life'), but Hou still expects viewers to notice details, make connections and draw conclusions. Flowers of Shanghai (Hai Shang Hua, 1998) is equally druggy in its presentation of the closed world of Shanghai's 'flower houses' just before the republican revolution arrives to sweep them away; here the protracted takes are often mobile rather than fixed-angle but no less objective - with the crucial exception of one 'shocking' subjective shot, which throws the rest of the film into relief.

Similar aesthetic strategies have dominated the third phase of Hou's career, those films in which he sets out to dissect contemporary urban life, almost always focusing on the marginalised figure of a woman. This strand in his output actually dates back to Daughter of the Nile (Niluohe Nüer, 1987), centred on a fast-food server's hapless crush on a gigolo, but it has come into full blossom since the present-day scenes in Good Men, Good Women.

Hence Millennium Mambo, in which the present is made strange by a voiceover that looks back at it from ten years in the future, and Café Lumière, which assigns the characteristics of quasi-independent young women in Taipei to a young woman in Tokyo - and, of course, the 2005 chapter in Three Times. In all these films Hou does his best to eliminate 'drama' entirely. He charts the ebbs and flows of everyday life, trusting the singularity of his women protagonists to hold the viewer's attention and the pared-down editing to highlight the details that he sees as essential to analysis and understanding of their mindsets and behaviour. He told me very recently that he will carry over the same approach into his upcoming French project with Juliette Binoche; it will examine the life of a middle-class woman through the observation of her Chinese babysitter.

There's been a small renaissance in Taiwanese film-making this year, but the Taiwan audience for local films remains elusive. Hou and Tsai Ming-Liang have led the way in campaigning to build up a new arthouse audience; Hou has even launched his own arthouse cinema in Taipei, the Spot, housed in the former residence of the US ambassador. (Edward Yang, on the other hand, found the situation so dispiriting that he refused to release A One and a Two... in Taiwan at all.) The bottom line, though, is that all creatively ambitious Taiwan directors rely on foreign finance and distribution to keep them working.

Hou's reinvention of his own film-making, summarised and encapsulated in the three chapters of Three Times, hasn't always been popular at home or abroad. The humanist stance of his mid-1980s movies posed no problem to critics and audiences schooled in neorealism and post-melodramatic cinema, but his formalised 'history' films and his seemingly free-form 'modern' films have been a tough sell. In that light, Three Times represents something of a breakthrough. Maybe its success will encourage viewers to explore Hou's matchless back catalogue on DVD.

Editor's note: The games played in the 'A Time for Love' chapter of Three Times are in fact billiards (in the first scene) and snooker (thereafter), not pool. But since Hou refers to pool halls and pool-girls and the film's subtitles refer to same we have left all references to pool untouched in this article. Our review on page 90 in the magazine, however, refers to snooker halls.