Primary navigation

The experimental films of Philippe Garrel are psychodramas haunted by his famous lover Nico and heroin. But his new Les Amants réguliers shows how 1968 turned poets into activists.

Considering how much admiration I have for the films of Philippe Garrel, it's hard to avoid feelings of guilt and consternation for not liking them more - especially when I consider how much they mean to others whose tastes I respect. For the past decade I've been trying to theorise my disaffection by ascribing the passion of my younger friends for this melancholy star of the French underground to a generational preference I can't share. In some respects, I even like the way they like Garrel's films more than I like the films themselves. Garrel's work generates a kind of awe few other film-makers inspire, and the fact that he's a minority taste in no way disqualifies him from being a major talent.

Strangely, most of the die-hard Garrel fans I know - many of them collaborators on Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (2003), a book I co-edited with Adrian Martin - were born over a decade later than him, whereas I was born five years earlier. I feel far more in tune with Jean Eustache, born in 1938, and Jacques Rivette, born in 1928, than I do with Garrel, born in 1948. The post-1968 political despair in Rivette's Out 1 (1971/72) and Eustache's The Mother and the Whore (1973) speak to me directly and urgently, whereas Garrel's recent Les Amants réguliers (Regular Lovers, 2004), which attacks the same subject in an even more literal fashion, seems to be addressing a different constituency.

Rivette's desperate vision is fully tuned into 1960s madness and Eustache's angry vision into 1960s neurosis. But Garrel's lament is neither desperate nor angry, and his 'regular lovers' are basically innocents, basking or drowning in the banality of bourgeois comforts. Maybe my friends and I were doing the same thing, but I can't recognise the portrait. Rightly or wrongly, we were fighting a game that had stakes, whereas these charming deadbeats don't appear to be.

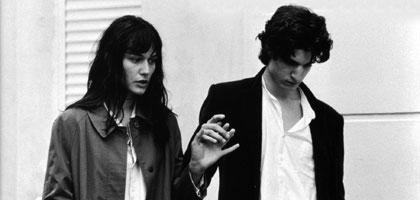

At least I can agree with Garrel's admirers that his three-hour epic about Parisian youth in 1968 belongs near the peak of his oeuvre. Shot in exquisite high-contrast black and white by William Lubtchansky, and virtually beginning with an account of the May '68 street skirmishes, it distils the brooding melancholy of his work as a whole into a nocturnal reverie about retreat. But I can't say I'm easily reconciled to the hopelessness of the film's vision, so maybe it can also serve as a useful index of why and how certain tastes and historical understandings differ.

An observation in an open letter to my co-editor Adrian Martin from Fergus Daly, organiser of the 'Garrel éternel' conference in Dublin in 2001, came closest to explaining my distance from the film-maker's younger fans. Alluding to "this preoccupation with the couple and little else (a persistent one in Garrel)," Daly notes that: "For those like you and I who developed their affective lines of investment and expectation as adolescents in the late '70s, politics in the accepted (macro-) sense was already a thing of the past - art and love seemed the only things that mattered." This is clearly also true of the characters in the second two-thirds of Les Amants réguliers, and can't help but affect the way we view their politics - and how we view them politically - during the opening third.

Garrel's first films were made in his teens, shortly before the upheavals of '68; apart from the hour-long, black-and-white Le Révélateur (1968), which was briefly available in France on video, these remain impossible for most people to see. Based on what I've sampled, and not counting his television commissions of that period (basically documentaries, including one about Godard), they resemble his subsequent work insofar as they're mainly autobiographical, focus on homey and everyday details while remaining detached and painterly, are inspired by silent cinema (Le Révélateur is literally silent), and employ actors associated with the French New Wave (including Garrel's own father Maurice, who worked for Jacques Rozier and François Truffaut, as well as Bernadette Lafont, Jean-Pierre Léaud and Zouzou). Unlike many other experimental films, they're mostly in 35mm.

Some of Garrel's more ambitious films of the 1960s and 1970s also take on epic and mythopoetic dimensions. The best known of these is probably La Cicatrice intérieure (The Inner Scar, 1971), shot in Egypt, Iceland, Italy and New Mexico with Pierre Clémenti, Clémenti's infant son Balthazar, Daniel Pommereulle, Warhol superstar Nico and Garrel himself. Nico went on to become the love of Garrel's life: she features in his next half-dozen films and it seems that most of those made after their separation and her death continue to evoke her in some way. The only other Garrel film with Nico I've seen, Les Hautes Solitudes (1974), is another silent feature, relatively non-fictional; Jean Seberg, Tina Aumont and Laurent Terzieff also appear in it, and the voyeuristic way it views Seberg, sometimes while she's sleeping or just waking up, struck me as intrusive. It's a development that heralds some of the more violent psychodramas in the later narrative features.

Since the 1970s Garrel has spent much of his time recasting his brooding style in terms more compatible with narrative conventions and arthouse norms, while sustaining his autobiographical preoccupations and never compromising his vision one iota. The influence of silent cinema remains in force, for instance, becoming especially apparent in his use of solo piano for musical accompaniments, including in the score by Jean-Claude Vannier for Les Amants réguliers. No less relevant are that film's poetic intertitles introducing various sections - despite the irony with which they're used, which often seems to reflect the irony of the enigmatic fantasy sequences evoking 18th-century military battles. In both instances Garrel seems to be looking back on his younger self with a certain indulgent scepticism while projecting an overall sympathy towards all his other characters (including even the cops) that is both refreshing and unexpected. Gabe Klinger, writing online, has even plausibly compared him to Jean Renoir.

Until fairly recently, the Paris Cinémathèque was mainly inhospitable to and incurious about contemporary experimental films. But Garrel, a particular favourite of founder Henri Langlois (who regarded La Cicatrice intérieure as a "total masterpiece"), is a notable exception. The fact that he grew up in some proximity to the local film world because of his father probably helped to establish him early on as legendary as well as highly respected. As Cahiers du cinéma's Jean Douchet has observed, Garrel's "small but devoted public" is essentially the one that has traditionally developed in France around poets.

As with Werner Schroeter in Germany and Carmelo Bene in Italy - two other avant-garde masters of slow-motion portraiture who developed over the same period - another pertinent parallel might be to chamber music. Even if Garrel's chosen style is far from the operatic and camp registers of Schroeter and Bene, there's a similar sense of transporting the viewer to a meditative, almost non-narrative realm, a soft and sombre perpetual present akin to the intimate world of a string quartet. Whatever one's qualms, it's a kind of cinema that needs defending today more than ever.

In this respect Garrel might be regarded as a kind of romantic luxury only a culture such as France's can fully support, or perhaps envision: relatively free from most commercial restraints, including many of the usual obligations associated with telling a story; surviving on the fringes of art cinema while retaining the same overall ambitions; defiantly remaining, as New York admirer Kent Jones put it in the title of one appreciation, 'Sad and Proud of It'.

It isn't clear to me whether Garrel met Nico before or after he became a heroin addict. I suspect it was after, because opium plays a significant role in Les Amants réguliers while Nico, apart from the use of her song 'Vegas', seemingly doesn't - though it's surely wrong to treat the autobiographical elements in Garrel's films too literally. François, the 20-year-old hero of Les Amants réguliers, played by the director's son Louis, is identified as a talented poet but not as a film-maker; his lover Lilie (Clotilde Hesme), whom he meets on the streets during May '68, is a French sculptress of roughly the same age, not a German-born pop vocalist who is ten years older. Yet it does seem evident that Nico and heroin were the two key elements in Garrel's life during the 1970s, that they largely overlap, and that both have haunted his work ever since.

Among those of Garrel's psychodramas I've seen, the two I've found most compelling are Liberté, la nuit (1983) and La Naissance de l'amour (The Birth of Love, 1993). The former - Garrel's only period film prior to Les Amants réguliers - is set during the Algerian war and has highly emotional performances by Emmanuelle Riva, Maurice Garrel and Christine Boisson. The latter oscillates between an actor (Lou Castel) undergoing a midlife crisis who periodically leaves his wife, teenage son and infant daughter to sleep with younger women, and a friend of his (Jean-Pierre Léaud), a blocked writer who's just been ditched by his girlfriend and can't get over her.

Sometimes Garrel's films are sufficiently direct in their personal references to be about film-makers and film-making. The most complex example is Elle a passé tant d'heures sous les sunlights (1985), which contrives to alternate the stories of two film-making couples in a splintered, ambiguous fashion, mixing documentary and self-referential fiction while also including Garrel's interviews with Chantal Akerman and Jacques Doillon. This 35mm black-and-white feature led to a 16mm colour television documentary four years later, Les Ministères de l'art, dedicated to the memory of Eustache. Here Garrel interrogates not only Akerman and Doillon, but also, among others, his best-known disciple Léos Carax, Léaud, Juliet Berto, Benoît Jacquot, André Téchiné and Werner Schroeter, most often while taking extended walks with them. He also manages to show his five-year-old son Louis, the future star of Les Amants réguliers, riding a tricycle while he pontificates nearby.

Finally, in Sauvage innocence (2001), we find a bitter personal allegory about film-making. A film-maker (Mehdi Belhaj Kacem) whose wife dies from a drug overdose arranges to make an autobiographical, anti-heroin feature, meanwhile becoming involved with his star (Julia Faure). Then, after losing his financing, he cuts a deal that involves helping his new producer (Michel Subor) - an addict who has meanwhile hooked his leading lady - to smuggle heroin into France.

Louis Garrel was one of the three young leads in Bernardo Bertolucci's The Dreamers (2003), another film set around May '68. This has understandably led many to interpret Les Amants réguliers as Garrel's response to that film - an interpretation he encourages when he has his characters briefly mention Prima della rivoluzione and cite Bertolucci by name. It should also be noted that Louis Garrel is one of the clearest assets of both films - not only due to his skill as an actor but because physically he evokes the era in question, often calling to mind Jean-Pierre Léaud.

But it should be stressed that the characters he plays in the two films are different, even if both come from unusually privileged and educated backgrounds. Theo - his more cocky character in The Dreamers, who throws a Molotov cocktail just to be part of the action - is a far cry from François, a more vulnerable and sheltered youth who isn't even sure he should publish his poems ("It would feel like betraying something - although I don't know what"), even if his writing talent is seemingly what wins him a suspended sentence when he comically goes to trial for evading the draft. (Warning: spoilers ahead.) François, who is ultimately both likable and doomed, can't even survive the shock of Lilie breaking up with him - an act rendered in a masterful two-minute take, shot on the street.

The Dreamers was supposed to show how great it was in 1968 to be young and horny and in Paris and political and smitten with movies seen at the Cinémathèque. I must confess that I was all of those things, yet the movie brought back none of my experience - perhaps because it was aimed at viewers the same age as scriptwriter Gilbert Adair's and Bertolucci's characters, not at me, even if one of those characters was an American cinephile like myself. Admittedly, I'd arrived in Paris that summer in mid-June, just after the police had taken the Odeon theatre back from the students and cleared away the makeshift street barricades. Yet remnants of felled trees still lined portions of boulevard St-Michel and the city felt strangely energised; I found myself fleeing from a police charge one day and getting a sudden and potent whiff of tear gas on another.

Unlike The Dreamers, Garrel's film is only about French kids, and it starts rather than ends with the May events. It feels much more authentic, presumably because Garrel was a participant at the time (albeit a "very non-violent" one, by his own account) as well as an observer. As film-maker Jackie Raynal, who worked as Garrel's editor and assistant director during this period, once told me in an interview: "Godard had an Alfa Romeo with a 35mm camera, and he and Alain Jouffroy and Garrel went around shooting footage," adding that, "Because of the Alfa Romeo, the police left them alone." (The ten-minute collective film that resulted, Actua I, which Godard has praised, was lost in a processing lab and never seen again.)

Authentic or not, Garrel's treatment of events is arguably no less postpolitical (or prepolitical) than Bertolucci's. One can admire his honesty about his characters' overall lethargy without being entranced by the lethargy itself, as some viewers apparently are. Given how supportive Francois' parents (and his grandfather, played by Maurice Garrel) are of his street activism, he doesn't come across as much of a rebel. The political discourse we hear ("Organising is for sheep - what we want is anarchism"; "Can we make a revolution for the working class despite the working class?") certainly matches the flavour of the time, but its overall function in the film isn't far from period decor.

Above all, the importance of drugs in Francois' life is established even before his political concerns are broached - with the result that his drug use can't help but inform his politics. It isn't clear to me if he's smoking hashish or opium with his friends in an early scene. But even if it's the former, opium clearly becomes the drug of choice soon afterwards. And you don't have to read the Appendix to William S. Burroughs' Naked Lunch to understand that the philosophical and political implications of hallucinogenic drugs and those of opiates are virtually antithetical, and were understood as such by a good many radicals of the 1960s.

This isn't an understanding Garrel appears to have much truck with. It's a comprehensible position for a former heroin addict to hold, but it can't illuminate why radicals who smoked grass in the 1960s didn't regard their activity as a political cop-out, whereas those who favoured heroin were unlikely to be involved with any sort of politics, except peripherally. Maybe that's why this film feels, like Keats in 'Ode to a Nightingale', "half in love with easeful Death" - almost viewing political defeat itself as a kind of voluptuous embrace.