Primary navigation

The BFI National Archive’s treasure trove of films about the mining industry doesn’t just reveal a lost world, says ‘Billy Elliot’ screenwriter Lee Hall. It reveals a lost set of values

"Constant revolutionising of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away... All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned... All old-established national industries have been destroyed or are daily being destroyed."

— Marx and Engels, The Communist Manifesto (1848)

The disappearance of the British coal industry seems in many ways less of a surprise than its subsequent cleansing from our cultural landscape, along with the figure of the miner. All those images and all that experience have disappeared, photoshopped out of our common imagination like the vanished commissars we tittered at with a totalitarian chill back in the 1980s, when those black-and-white Soviet photographs came to light. Apart from a few television shows remembering the 1984 strike, the 1900 years of British mining seem to have melted into air.

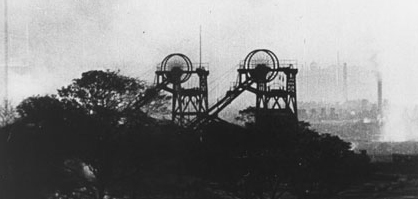

Even in 1996, before the final eradication of the industry, I drove around the Durham coalfield looking for locations for Billy Elliot, but there was not a winding gear to be seen. As soon as the pits closed, all physical evidence was erased in what seemed to be a concerted act of cultural cleansing. What had been until ten years previously the engine of our economy (even in early 1984, 75 per cent of our energy was produced by coal) was now simply gone – grassed over, airbrushed out, as if the grand age of carboniferous capitalism was in some ancient Victorian past.

The true apogee of the mining industry is, of course, much closer to us. The industry actually reached its peak in the 1920s, when 1.2 million men worked in the mines; and even now a third of our energy is still derived from coal – though we ship it in from places like China and the Ukraine (despite their safety conditions being comparable to our industry in the 1870s). But if coal is so conclusively over, why, in an age when we have an insatiable appetite for bonnets and bustles and all things historical, has the humble miner disappeared from our field of vision?

The answer lies in the BFI National Archive’s extraordinary collection of film of the mining industry. There are thousands of individual films, and the range is vast: everything from industrial promotional films to home-made campaign videos produced during the 1984 strike. What all these films have in common (left or right) is a concern that coal, the people who dug it up and the industry in general, were intimately connected with the fate of the nation. During those years no picture of Britain was complete without a view of coal. The 1946 nationalisation of the industry, a cornerstone of the post-war settlement, welded the industry even closer to the national interest; crucially, that’s why in the post-1984 hegemony – where Britain makes its money through money rather than labour – imagery of the old consensus is particularly unacceptable.

Last year the Guardian calculated that the cost to the nation of dismantling the coal industry has been upwards of £36 billion since 1984. The fact that the attack on the industry was ideological rather than economic is pretty much conceded from all political positions – and any doubt is certainly nul and void in an age when ‘uneconomic industries’ can so easily receive trillion-dollar bail-outs. The Thatcher attack on the mining industry was a watershed moment in post-war politics; as the strike was lost, so was an aspiration about Britain. Supposedly the working classes are now dead, money is made by some harmless algorithm in the sky and it is OK to be deeply unworried by filthy riches.

Shape and narrative

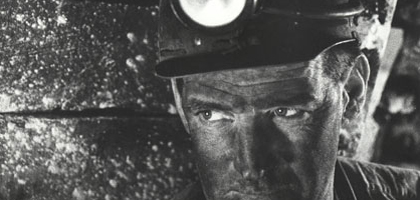

Looking at just a fraction of the archive’s films, you see that today’s Britain is so far from the joined-up country our forefathers knew – where our interdependence and mutuality were implicit in any sense of prosperity, let alone social justice. And it is so much clearer why we might be in the mess we are in. It’s clear even from the earliest films such as A Day in the Life of a Coal Miner (1910) that the central character – this is a strange hybrid of document and reconstruction – represents more than simply someone who works underground. The harshness of the work and the care to set it in the context of home and therefore community are testimony to the implicit respect the audience would feel for this otherwise humble and inauspicious employment. There is, as in the Mitchell and Kenyon films, the thrill of seeing real people so distantly past, but what is remarkable is the sense of shape and narrative given to the material. There is more here than the sheer spectacle of witnessing the real world at one remove – there is the sense of a meaning being built; film giving weight and shape to lived experience.

The full symbolic force of the miner is probably most famously celebrated in Cavalcanti’s 1935 short Coal Face – yet for all the supposed modernism of Auden’s narration, Britten’s music and Cavalcanti’s avant-garde past, it is the reality of life underground which is most arresting. Even in Auden’s commentary, the bald statistics about injuries and fatalities move us more than his more poetic speculations. Mining was an especially dangerous employment; right through the 1950s, despite all the technological advances, a miner was killed every day.

Civic focus

In cinematic terms it’s easy to see the heroic, Promethean aspects of a miner’s endeavour as he descends into the underworld to retrieve the source of fire. But what is interesting is how the film-makers strive to tell a more complex civic narrative. What Cavalcanti draws for us is our connectedness to these men. So you can sit in a nice warm parlour, some bloke is getting up at five in the morning and hewing coal underground. That we are part of a whole, dependent on each other, is crucial to the vision. What is subterranean – obscured by darkness, invisible from the surface – is literally revealed. But what animates Coal Face is not simply the excitement of vérité – of witnessing the drama of these lives, these industries – but the attempt to make sense of it. As Auden realised, it’s not enough just to see these guys slogging away – we have to understand the context. This insight sets the tone for almost all of the subsequent films that have been chosen for the BFI’s season and DVD collection.

The great treasure in the archive is the collection of films from the National Coal Board, in particular the Mining Review cine-magazine series. Filmed from 1947 to 1983, the films were shown in several hundred cinemas, usually featuring three or four stories at a time as an omnibus look at the concerns of the coal industry. There are over 400 Mining Reviews (and almost a thousand films in the NCB Film Unit collection), looking at every imaginable aspect of the industry. Of course there is a ‘promotional’ tone in most of the films, but as they were largely made by the DATA co-operative, a group of left-leaning film-makers, these films are always sensitive to human pathos and the political complexities of working in a hard, dangerous but recently nationalised industry.

Very little about the British miners seen here is Stakhanovite. They are rather slight, mellow chaps; what distinguishes them is their culture rather than brute force. The importance of family, of community and – surprisingly – art is very clearly drawn in the films. I had no idea that there was film footage of the Pitmen Painters of Ashington, a group of working miners who became celebrated artists (and the subject of my most recent play), but here they are diligently painting away in one of the films. Here is the world of choral singing, brass bands playing Vivaldi, the prolific tradition of songs from the coalfields, and so much evidence of the self-sustaining culture of education whose roots are to be found in the Victorian unions rather than the Butler Education Act. One particularly endearing film is about the Balletomines, a group of Yorkshire miners who parody Coppélia in local halls. The knowing ridiculousness of the miners’ supposed aspiration to be ballet dancers sits firmly in a tradition where the miners knew how to make their own entertainment – the band are no strangers to Delibes’ famous score.

The filming conditions, of course, were profoundly difficult. No electrics could be taken underground and right up until the 1980s these films were shot with the same 1930s wind-up cameras that Cavalcanti had used in Coal Face. But the ambition was huge, and there was always an attempt to make each film not only visually interesting, but an illustration of the bigger narrative of the post-war settlement.

It’s difficult for someone of my generation to imagine that an industry could have its own film unit, and that its productions might be served up in cinemas across the land. While there is a quaintness about some of the early films, the unrolling narrative about technological change and its effect on individual lives and the greater community is told through snapshots of very real people. The ‘white heat’ of the Wilson years was fuelled, we remember, by folk underground; one of the most evocative of these films – Miners (1976) by Peter Pickering – has a 1970s feel that would not be out of place in an early Fassbinder movie.

But it’s the confidence of the film-makers in exploring the mechanics of the industry that most surprised me. I constantly expected to find fun in the iterations of new technology, as if they were Soviet broadcasts of grain yields. But they are always interesting – the machinery imaginatively shot, the stories not the least bit predictable. We realise how much is now hidden away from us. The idea of these films is to bring all that is hidden into the light, show us what we rely on, what we owe. These films are not really about venerating the men who do the dirty work, but about celebrating the notion of the national machine.

Black comedy

The cinematic qualities of actual mining have had scant attention from makers of drama. It is interesting that so few films have exploited the obvious imagery of the world underground: the darkness and light, the danger, the claustrophobia. Of those dramatic films set in the world of coal, most deal with life above ground. But Carol Reed’s The Stars Look Down (1940) is probably the main exception as it concentrates on a particular episode of A.J. Cronin’s source novel involving an accident underground. Reed’s film seems to my eyes a more believable picture of mining life than John Ford’s Oscar-winning How Green Was My Valley, made a year later.

But my favourite mining-related drama is Ken Loach’s Meet the People (1977), one of two linked plays written by Barry Hines for the ‘Play for Today’ strand under the title The Price of Coal. The salty wit employed in showing the ironies of a royal visit to a pit seems to dig at the heart of the matter. The contradiction of the experiment in socialism in a mixed economy, as Herbert Morrison described it at the 1947 Durham Miners’ Gala, while we were still a monarchy is unpicked here in all its absurdity. That the market as a whole was unregulated meant in many ways that the mining industry was ultimately more vulnerable in public hands than it might have been in private ones. On the eve of nationalisation, miners were paid 30 per cent above the national average, but by the time of the 1984 strike they were paid well below. The bigger point that the mining industry symbolised the utopian urge for a common wealth runs through virtually every film here. Loach, typically, plays out the national drama with comic panache. Simple, ordinary lives bear the weight of these massive structural contradictions.

What is made clear in these films is what Thatcher wanted to conceal: that the industry and the people in it represented the bedrock of a post-war consensus in which we were all inextricably linked, contingent on each other, our resources both human and mineral held in common. If you want an alternative to the received opinion of miners as crazed, thuggish leftists, look at any one of these films. What is most moving about them is the attempt to show ‘ordinary people’. Not heroes, not idealised or sentimentalised. Perhaps nowhere is this caught with less self-consciousness than in the workshop films made during the 1984 strike. The moving testimonies of miners’ wives about the privations they are rising above and the strength of their solidarity are stirring not just because of the rhetorical eloquence of the women, but because of the ordinariness of their voices.

Ordinary people

The depiction of the ordinary and mundane in these films is really their point – our common life is made of such stuff. That this ‘ordinariness’ can be visually arresting, politically pertinent and a source of emotional complexity is the triumph of the whole British documentary movement spawned by John Grierson.

The makers of these films and the participants in them saw Britain in a different way. They knew what went on under the bonnet. They knew you don’t make money out of thin air – somebody somewhere is down a hole digging for it. That we have outsourced the dirty work is one thing; that we refuse to look the fact in the eye is another. And that’s what these films refuse to shy away from. Modern life, cinema included, is an industrial enterprise and – whether it conceals the fact or not – cinema is a record of work. And it is this celebration of ordinary labour which ruffles the political orthodoxies of the post-Thatcher age. The image, now so unfamiliar in the era of the consumer, of the working classes as producers of culture as well as coal is reason enough to see these films.

This is just the start of a major revisiting of the industrial legacy in the BFI National Archive – shipbuilding and steel are next. It is a provocative and at many times moving undertaking, pretty massive in its scope. But it’s important to see such films, lest we forget where we come from – and what has been denied us.

The season ‘This Working Life: King Coal – A Century of British Coalmining on Screen’ is showing at BFI Southbank, London, until the end of September, and at Sheffield Showroom until October 15. ‘Portrait of a Miner: National Coal Board Collection Volume 1’ is released on 21 September on BFI DVD