Primary navigation

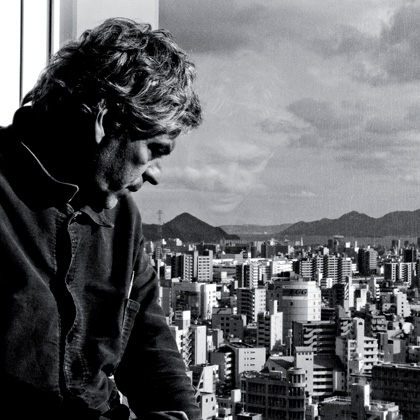

The films of Pedro Costa have reinvented the relationship between film-maker and subject. Kieron Corless talks to the Portuguese director

The films of the 50-year-old Portuguese director Pedro Costa have been captivating audiences on the festival circuit for nearly 20 years, but with the exception of a one-cinema release for his Colossal Youth (see S&S May and June 2008) none has so far been distributed in Britain. Now, with a complete Costa retrospective at Tate Modern in late September and several DVD releases pending through Second Run and Eureka/Masters of Cinema, British cinephiles can finally acquaint themselves with his singular talent, which first expressed itself in visually striking early works such as O Sangue (1989) and Casa de Lava (1994). However, it was the so-called Fontainhas trilogy – Ossos (1997), In Vanda’s Room (No Quarto da Vanda, 2000) and Colossal Youth (Juventude em Marcha, 2006) – which really made the world sit up and take notice; the latter two in particular are widely regarded as key films of the last 20 years.

Costa’s discovery of Fontainhas, a ghetto neighbourhood on the outskirts of Lisbon that’s home to impoverished immigrants from Portugal’s former colony the Cape Verde Islands, led to his increasing disillusionment with industrial film-making and his switch to small-scale digital work. Costa’s subsequent films made with non-professional actors essentially playing versions of their own often bleak lives were underpinned by his striving for a truly collaborative and more rigorous film-making practice – ‘a cinema made with justice’, as he styles it, drawing for its inspiration on the likes of John Ford, Chaplin, Ozu and Straub-Huillet. (Straub, in particular, he calls his "master".)

How did you start in film?

After film school in 1981, like everyone I got some small jobs on productions – getting the sandwich for the actor, driving the car. I was young, it was money – actually I earned much more money than I am earning now – and I was a bit afraid, I have to say. I didn’t like what I saw. I worked for six or seven years as assistant. Every film I worked on I saw the same thing: a lot of tragedies and massacres, producers against directors, crews that weren’t interested in the film, directors panicking. So I kept wondering, Is this the life I want to have? But this was a moment when state funding started here and Portuguese films were a bit fashionable. There were a lot of film-makers coming here – Wenders, Ruiz, Tanner etc, and the producer Paulo Branco was very active. So there was a lot of energy, let’s say, and I got some money to do a first film, O Sangue.

What was influencing you at that time?

The English band Wire and Godard and Straub were my heroes. And they all seemed exactly the same thing for me. Not at all difficult or intellectual. Very simple, very practical, talking about day-to-day life, and very sensual – the most sensual films and the most sensual music. But it could also be Ozu; some felt he was traditional or reactionary, but for me he was the most advanced, progressive, the fastest of film-makers. I felt contemporary to these things, and less to the films that were made during and after the Portuguese revolution, documentaries that were made here and everywhere at that time, left-wing things saying "Cinema is a weapon" and all this bullshit.

You’re mainly associated with the loose trilogy you made in Fontainhas – ‘Ossos’, ‘In Vanda’s Room’, ‘Colossal Youth’. How did you come to that neighbourhood?

I made my second film in Cape Verde, called Casa de Lava. I wanted to do this story which actually was a remake of [Jacques Tourneur’s 1943] I Walked with a Zombie, or it was supposed to be, with zombies and dogs and strange people. And then when we made it, of course it was not at all a remake, but a very difficult thing to do because we had to bring everything, even our own electricity and trucks. It was a mini-Apocalypse Now for us, but what was good for me was I felt a possible way of doing things, of being closer to some people, real people. In fact in the last days I got close to the people in the village where we shot. On the last day when we were leaving, they gave me a big plastic bag full of letters and tobacco and rice and coffee for their relatives who were here in Lisbon, in Fontainhas. I knew where the place was – it was a real ghetto and really dangerous. I spoke some creole and so when I found the people there, I was immediately accepted because I brought messages. And then they kept inviting me, "You must come to dinner tomorrow, you must come Saturday to this party," and I began staying.

Why did you keep going back? What attracted you?

I have to admit that my first attraction was almost sensual, plastic – the colours, the skin colours, the way they talked. It was a lot of music, hearing sounds. I thought this could be a nice world for me to try to film. Even the place seemed like a small studio: all the houses and the street – it was like a set.

How did ‘Ossos’ come about – it seems like the transitional film in your career?

I met Vanda [Duarte], her mother, sister and then another guy, and then I just got this idea of a baby being born and the parents not wanting it. They want to sell it, which was a common story, a cliché, in that kind of place, that kind of world, I learned a lot of things with that film, because at the same time as I was beginning to think I had found something and I had found a world, at least some people that I really like, and that those people were going to be in front of the camera, still I had a problem behind the camera which in that film was a big, big mess.

So out of this experience you started thinking of a new approach?

I was in fact already thinking about the next film, a correct approach and way of working in that place – about the organisation and about how you keep film in its place so it’s not a violating thing, a police thing. There’s a lot of things that I cannot do in that place. I cannot say, "Silence" – it’s absurd. It means "Don’t talk. Stop the music" – and that’s what I like! So it’s step by step, and it took me a long time.

How important was Vanda Duarte in taking you to this new place?

In Ossos she was the one who resisted all the time. Everything you read about Mitchum, when he was, "Yeah, yeah I’ll do it" – and then he did something else. Same with Vanda. She was never on the spot for the light, never. When I said "Good morning," she would say "Good night." She hated the cables, the guys, the trucks – she said this was completely fake. So she gave me the reason.

By the end of the shoot I was completely exhausted, and she said, "Come back and try to do it in another way. Come to my room and stay a bit and think." So there was this kind of invitation to do something with her in her room, which for me was a dream because a room, a girl, a camera – well, for a heterosexual film-maker it can be very tempting. So I thought about that and just went there, bought this camera, put it in my backpack and began coming. No project, just this room and this girl.

So this was the start of the process that eventually led to ‘In Vanda’s Room’?

In fact two months after I was there she came to her room with stuff and said, "Are you still thinking about something?" I said, "Yeah, we’re doing it." It was so small, she didn’t realise there was something happening. That was good because nobody was paying attention. They knew it was another film, but it was not about glamour, it was more concrete – there was just one guy. I tried to show them that it is also very hard and I had to be there every day, for myself, for discipline.

Could you describe in a bit more detail how you work with the digital camera?

When I am making a shot with a very small video camera it is exactly like making the shots I did before. The work is done with exactly the same gentleness and care and precision. You have to be much more careful, actually – you should take it slower. These cameras seem to have a sticker saying, "Move me or do what you want" – but you should not move it. You should take your time, do it slow, think. For me it is like a microscope – it’s much more risky than shooting in 35.

Can you say something about how you work on a day-to-day basis?

It’s about having a common idea and making it happen. Some very fragile and simple tools – a camera, a mic – and some props, very simple things from the neighbourhood. They dress how they dress. But it’s from eight to seven, or nine to ten in the evening, every day. Colossal Youth was made from Monday to Saturday, then Sunday rest, for one-and-a-half years, with some pauses. We have the freedom of not shooting when we don’t feel like it. We have the freedom, if Ventura [the lead actor in Colossal Youth] is not well or Vanda, we do not force them to work of course, and that creates a very good spirit because they actually become more committed. That’s a good part of this method. The film takes its own pace. It’s much more in your body, in the body of your actors; it becomes daily, it becomes work.

Do you rehearse?

Actually I’m doing something that I always dreamed of, doing exactly what Chaplin did when he started, which was rehearsing on film. Like in that Brownlow documentary about Chaplin, Unknown Chaplin, you can see he worked on film. He never rehearsed or tried anything without filming, without having the camera on, and that helps a lot. It takes solemnity and mystery out of the camera. The camera shouldn’t be a mystery.

You’re famous for doing a large number of takes. What are the advantages of that method?

There’s something about repetition – of course with some liberty, they are not nailed to the ground – that makes sense, that connects them to life. For [people in Fontainhas] much more than for other classes, their life is repetition – there’s nothing that’s going to change.

I think the record was 80 takes, but it needed 80 takes. We could do 30, 40, 50... Of course these takes are not made like in other films in one day, they are made in weeks. We could spend almost months doing a scene or just two scenes. There are no bosses or producers coming; we just feel that if it’s there, we cannot go any further, then we stop. And it’s good for them to have this discipline, to understand they can conquer their fear and insecurity and do it better, and tell it better. They can get to a point where it’s more clear and more mysterious at the same time.

How do you manage to survive financially?

It’s very simple making a budget – it’s having the money just to live every month, me and three or four friends. One for the sound, one to help me with the camera, another to assist me, and the actors of course. We try always to have this balance or harmony, all being paid more or less the same. That helps a lot. And in this kind of place it’s very important. It tells them film isn’t something special. I want to teach them that cinema is not a luxury, it’s not just made for very rich and glamorous people – it can be made with less money, it can be made with justice. It’s more about that than the artistic work for me. And that’s very good, because they now understand that. At the same time it’s very, very hard – it’s real work. But it’s something that has a relation still to the real world, and that was something I didn’t find in the films I assisted on, even some films I made with crews.

How have the people in Fontainhas responded to the films you made in the community?

That is what some of my colleagues don’t have, the ones that work in the more normal way – they don’t have this immediate critique that I have. You can imagine that after In Vanda’s Room, all the neighbourhood said, "Yeah, it’s great, it’s very beautiful, but there’s a lot of drugs. We are not about drugs and now you should show some other things." It was very serious, it was very Maoist. I defended myself. I said, "Yeah, well it’s my thing about you." This kind of thing is very useful to me: it’s my fear of not losing touch with this thing that I am associating with cinema, this part of humanity or reality that I think was always there since the beginning – and sometimes it’s not there enough even in documentaries you see.

A retrospective of Pedro Costa’s films screens at Tate Modern from 25 September to 4 October. ‘O Sangue’ is released on DVD on 21 September, followed by ‘Casa de Lava’, ‘In Vanda’s Room’ and ‘Colossal Youth’ in early 2010

See also:

Exile and the kingdom: Jonathan Romney reviews Colossal Youth, our June 2008 Film of the Month