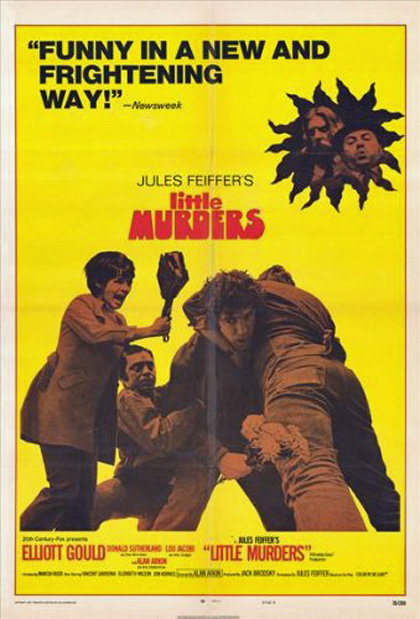

Lost and found: Little Murders

Jim O’Rourke lauds Alan Arkin’s 1971 directorial debut, a quintessentially New York story of existential angst

The first time I saw Alan Arkin’s Little Murders (1971) was in my family’s basement, the one place I was sure I would be left alone. I knew little to nothing about it, except that the discontinuity of its title and its reputation as a comedy was enticing. About ten or 15 minutes in, Elliott Gould turns to Marcia Rodd and says – with great apprehension, but also the calm that only a universal truth can bring – that he “hates families”. On that day 30 years ago, I knew I’d found the movie for me.

Based on Jules Feiffer’s play, Little Murders was shepherded into production by star Elliott Gould, with much the same cast as the stage version. The film was the directing debut of actor – and producer, singer, composer, author – Alan Arkin (could I also nominate his second film Fire Sale for a future column?).

It centres on photographer Alfred Chamberlain (Gould), who has become so uninterested in his life and work that he decides to float through existence, leaving no imprint, never reacting – even to a beating from strangers as the film opens. Instead he just lets life’s events pass him by so he can focus all his energies on his consuming passion: taking photos of… well, that would be telling.

Alfred’s apathy is in stark contrast to the engaged hyperactivity of his new girlfriend Patsy Newquist (Marcia Rodd). Despite their differences, she introduces him to her family, and they are married by a spaced-out minister played by Donald Sutherland. Their life together, though, is threatened by the fact that their home city of New York has spiralled out of control to become an ultra-violent urban dystopia, where strikes, blackouts and random murders occur daily.

Born on the cusp of the Vietnam War, and with my first memories rooted in the Nixon years, I was vaguely aware of the kind of paranoid culture that seemed to spew forth from entertainment outlets at that time, but became fully acquainted with it in a strange, time-delayed fashion. Before there was cable in Chicago there was ‘scramble box’ one-channel pay television, and one company in particular showed nothing but the lowest-rental films. Besides Little Murders, there was a never-ending cavalcade of American negativity in films such as Aram Avakian’s End of the Road (1969), Stuart Rosenberg’s WUSA (1970, with Paul Newman), Peter Fonda’s Idaho Transfer (1973), Robert Downey Sr’s Putney Swope (1969) and Greaser’s Palace (1972), among countless others. Downey Sr’s films exerted a tremendous influence on me that lasts to this day, but there was always something about Little Murders that turned me into a bit of a proselytiser, insisting to friends that it was something they just had to see.

Compared to a film like Greaser’s Palace, Little Murders is easier for some to watch, with roots in recognisably ‘normal’ filmmaking – something the uninitiated could hang their hats on. Alongside Gould’s excellent turn as Chamberlain, the cast includes the wonder of Vincent Gardenia as Mr Newquist – the rather befuddled and paranoid father of Patsy and interrogator of her many would-be paramours – and the amazing dynamo of Jon Korkes as Patsy’s loving brother Kenny, who has a few problems of his own. Equally appealing is the early-1970s New York flavour that now seems to be lost forever – and which was also essential to the feel of films like The Taking of Pelham One Two Three and Putney Swope.

Little Murders stays close to Feiffer’s original play, which had a biting, acid-like sting, and shares that unhinged way of walking the line between cornball and eye-widening dissociation that I loved in the work of Downey Sr or Lenny Bruce. Most of all, the film has that endearing quality of starting off in a not very good place and going downhill from there. Of course, such a progression is not uncommon in drawing-room dramas, but a comedy that starts out having little faith in mankind – and then chooses not to redeem its characters, but instead to push the four walls closer in – doesn’t come along all that often.

The film follows an unsettling course to its unforeseen destination. Early on it shows its roots as a stage play, with broad swipes at squares and social mores; but as the underlying sense grows that ‘something is going on here’, the laughs give way to a more pointed desperation that you feel not in your gut but in the back of your neck. And yet we continue to laugh. It’s a remarkable balancing act that pushes us beyond laughing at what we are afraid of into an almost catatonic state in which we just let things slide past, unable to veer away.

This is not as simple as a careening car without brakes barrelling down the hill (Gould would do that later in Capricorn One); there are some truly awe-inspiring off-ramps, and one in particular left an impression with me to this day. I read that the artist Vito Acconci was profoundly influenced and moved by Jack Nicholson’s long soliloquy at the beginning of Bob Rafelson’s film The King of Marvin Gardens (1972), which forms an almost separate short film of late-night radio storytelling, his words sent out into the void. The sequence represents a way to sidestep the screen to speak directly to the audience, without ever acknowledging them. In Little Murders, for me that moment comes in Alfred’s pivotal central soliloquy, which threatens to split the film in two.

At a moment of crisis for themselves and their relationship, Alfred calmly and intently tells Patsy of his days in college when he was politically active and began to fear that he was being monitored for his participation in demonstrations and other political work. Feiffer takes this confessional down very unexpected roads, reaching a conclusion that is both bitingly cold and alarmingly revealing. Up to this point Alfred has seemed almost to be an empty vessel, ignoring the advice of those who tell him to engage with the world and find some meaning in his life. As he tells the story of his earlier ‘engaged’ life, he shows that he in fact has much more profound insights into the true meaning of his relationships than those who feel they are pulling him out of the water.

Dark clouds gather, the anti-deus ex machina descends and the film teeters on the brink of stifling its momentum or turning on its ear – in such a way that, as we move from spectator to confidant and back again, we realise not only that our narrator is much more reliable than we’d thought, but also that he is totally alone in his understanding of everything around him and everything he has chosen to ignore. And that includes us.

Jim O’Rourke is a musician, record producer and filmmaker. His albums include Bad Timing and The Visitor. He recently composed the score for Wakamatsu Koji’s United Red Army

What the papers said

“[Little Murders] falls somewhere within the category of satire… One of the reasons it works, and is indeed a definitive reflection of America’s darker moods, is that it breaks audiences down into isolated individuals, vulnerable and uncertain. Most movies create a temporary sort of democracy, a community of strangers there in the darkened theater. Not this one. The movie seems to be saying that New York City has a similar effect on its citizens, and that it will get you if you don’t watch out.”

— Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times, January 1971

See also

Lost and found: The Liberation of L.B. Jones: Neil Sinyard on William Wyler’s controversial and racially charged final film (January 2011)

Lost and found: Penn & Teller Get Killed: Brad Stevens on the late Arthur Penn’s overlooked final film (December 2010)

Cerebral subversive: Peter Biskind remembers the late Arthur Penn (October 2010)

Sight & Sound’s 30 key films of the 2000s including United Red Army (February 2010)

Royal rapscallion: Andrew Collins on Gene Hackman and the explosive new American cinema of the late 60s and 70s (November 2005)

Giant steps: David Thomson on the maverick new talents in early 1970s Hollywood (September 2006)