DVD: The Elia Kazan Collection

US 1945-63

Reviewed by Graham Fuller

Review

The Elia Kazan Collection

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn / Boomerang / Gentleman’s Agreement / Pinky / Panic in the Streets / A Streetcar Named Desire / Viva Zapata! / Man on a Tightrope / On the Waterfront / East of Eden / Baby Doll / A Face in the Crowd / Wild River / Splendor in the Grass / America America

Elia Kazan; US 1945-63; Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment / Region 1 NTSC; 128 / 88 / 118 / 102 / 96 / 122 / 113 / 105 / 108 / 115 / 114 / 126 / 109 / 124 / 168 minutes. Features: ‘A Letter to Elia’ documentary directed by Martin Scorsese and Kent Jones (2010); ‘Streetcar’ and ‘East of Eden’ are packaged with separate discs of extras

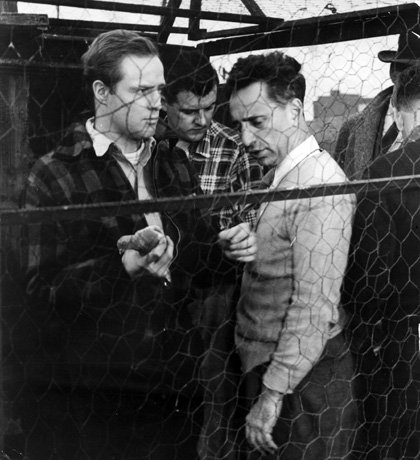

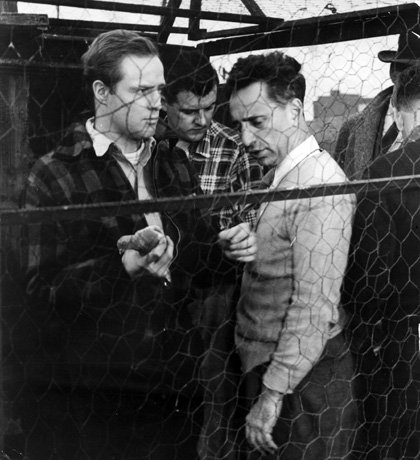

In curating this formidable box-set, Martin Scorsese has chosen to include 15 of Kazan’s 19 features – a body of work that comprises the most sustained inquiry into psychological and social flux by any American filmmaker in the post-war period. It includes critiques of poverty (A Tree Grows in Brooklyn), anti-Semitism (Gentleman’s Agreement), racism (Pinky), communist oppression in Eastern Europe (Man on a Tightrope) and the Red Scare in America (allegorically in Panic in the Streets), female dependence on men in the South via Tennessee Williams (A Streetcar Named Desire and Baby Doll), revolution (Viva Zapata!), union corruption (On the Waterfront; Kazan directing Marlon Brando pictured at top), puritanism and generational conflict (East of Eden, Splendor in the Grass), the manipulative power of television (A Face in the Crowd), rugged individualism, the New Deal and segregation (Wild River), and the immigrant dream (America America).

Nobody else at their peak in 1950s Hollywood – not Hitchcock, Wilder, Sirk, Stevens, Minnelli, Zinnemann or Kazan’s old hitchhiking buddy Nicholas Ray – matched Kazan for energy, eclecticism, the strength of his liberal convictions, or the ability to inspire and manipulate actors. Although he couldn’t cure Dorothy McGuire of her ladylike mannerisms in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, or melt the rigidity of Dana Andrews in Boomerang and Gregory Peck in Gentleman’s Agreement, those dated 1940s films were Kazan’s apprentice efforts, and it was he who presided over the Method-driven evolution of American film-acting from the enunciative to the naturalistic.

Following On the Waterfront, in which Marlon Brando’s longshoreman morphs from Mafia stooge to stool pigeon to hero, characterisation in Kazan’s films meanwhile expanded from the simplistically black or white to the ambivalent. Thus the ‘bad’ son Cal (James Dean) and the ‘good’ son Aron (Richard Davalos) change places in East of Eden. Archie Lee (Karl Malden) remains the ridiculous, shabby Southern aristocrat in Baby Doll but grows in what Kazan called ‘humanness’, as does his teenage virgin bride (Carroll Baker) and his rival (Eli Wallach). Jo Van Fleet’s obdurate landowner and Montgomery Clift’s idealistic government lackey, who has come to evict her from her Tennessee home, are both right and both wrong in Wild River, which increasingly looks like one of Kazan’s finest films. Even the sexually repressive mother who drives the fragile Deanie (Natalie Wood) mad in Splendor in the Grass senses by the end that she may not have acted in her daughter’s best interests.

One of Kazan’s great strengths was rooting the political in the intimate. Peck’s journalist character learns more about bigotry against Jews from his supposedly liberal fiancée (McGuire) than from his undercover foraging as a Gentile pretending to be Jewish. Stanley and Blanche in Streetcar, Cal and Abra in East of Eden, Baby Doll and Silva, Marcia and Lonesome in A Face in the Crowd, Chuck and Carol in Wild River and Deanie and Bud in Splendor all dance sexual pas de deux that highlight their social dilemmas. And stylistically, Kazan, coolest of metteurs en scène, sometimes out-Sirked Sirk: the smashing of the mirror that symbolises Stanley’s rape of Blanche destroys her fragile narcissistic existence; the attempt by Bud’s dissolute sister to kiss her autocratic oil baron father, both doomed, on the New Year’s Eve before the Wall Street Crash, suggests that his business and his blood are symbiotically tainted.

This fraught intimacy extends to the relationships between fathers and sons in Kazan – Cal and Adam in East of Eden, Bud and Ace in Splendor, Stavros and Isaac in America America. In the television documentary directed, co-written and presented by Scorsese that’s included here, he explains with utmost tenderness how, on seeing East of Eden as a 12-year-old boy, he identified with Cal as an underappreciated younger brother desperate to please his father – and how as a result he started to cast Kazan “in the role of a father”. (Frightened of his father and made to feel that he was a disappointment, Kazan too had identified with John Steinbeck’s original Cal.)

The Kazan films that Scorsese has omitted from the set are his second, The Sea of Grass (1947), an anonymous Tracy-Hepburn ranching melodrama on which he was constrained by MGM, and his last three: The Arrangement (1969), based on a semi-autobiographical bestseller about commercial compromise; The Visitors (1972), a minimalistic post-Vietnam War revenge drama shot in 16mm; and The Last Tycoon (1976), which suffered from Harold Pinter’s incomplete Fitzgerald adaptation and Kazan’s apparent lack of appetite for fighting producer Sam Spiegel over key creative decisions. The key absence may be The Visitors, which explores the personal cost of assigning guilt rather less self-servingly than did On the Waterfront, made two years after Kazan had named eight former fellow communists from his Group Theater days before the House of Un-American Activities Committee in 1952. His momentous decision to do so, which he considered the lesser of two evils, scarcely detracts from his power as an artist. Scorsese, for one, believes it turned him from a ‘director’ into a ‘filmmaker’.

See also

The best film books, by 51 critics including Elia Kazan’s A Life (April 2010)

Down in the hole: Kent Jones on The Wire (May 2008)

The gun beneath the bubbles: John Exshaw on Eli Wallach (January 2006)

Death’s cabbie: David Thompson on Martin Scorsese’s Bringing Out the Dead (December 1999)

Bamboozled reviewed by Xan Brooks (May 2001)