Primary navigation

A few years before Tarantino, writer-director Eric Red was playing bloodstained genres games in his 1988 debut Cohen and Tate. But where is he now, asks John Wrathall

Serial killers work alone, but hitmen come in pairs. Or at least they do in the movies. Pulp Fiction’s Vincent and Jules are probably the most famous example of a tradition that stretches back to Hemingway’s 1927 short story ‘The Killers’, via the Siodmak and Siegel movies it inspired – or perhaps even to the First and Second Murderers hired by Macbeth to assassinate Banquo (though Shakespeare cheated by having an unexpected Third Murderer turn up to help them on the night). But before Vincent and Jules there were Cohen and Tate; and before Tarantino, there was Eric Red.

In the late 1980s, when I first started reviewing films, US cinema was in a definite creative slump (these were the years when Oliver Stone was fêted as a great white hope). The movie brats of the 1970s had hit midlife crisis, and the Sundance/Miramax generation of the 1990s hadn’t quite come of age. We were all waiting for the next big thing to arrive, and for a while I thought Eric Red was it.

In the space of three years, when he was still in his twenties, he wrote three lean, mean movies that reworked and blended genres in exciting and visceral new ways. The Hitcher (directed by Robert Harmon, 1986) may have owed a lot to Duel, with the truck replaced by Rutger Hauer, but it established Red’s blend of gallows humour, expertly engineered suspense and flashes of horror, all in a distinctive road-movie world of lonely service stations and truck stops. Better still was the hugely influential Near Dark (1987), co-written with its director Kathryn Bigelow, which unleashed a family of trailer-trash vampires into the same desolate milieu.

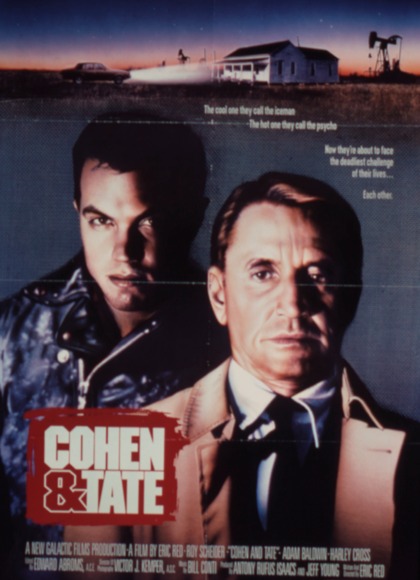

Writers with this distinctive a style and vision usually want to direct, and so it proved with Red. Cohen and Tate (1988) was his first film as director, and its opening sequence shows off his fluency with mixing genres. The setting – an isolated Oklahoma homestead, complete with whirring windmill overhead – is straight out of a western, and there’s a definite echo of The Searchers as a child (nine-year-old Travis, played by Harley Cross) runs out of the house, just in time to witness the impending massacre from a distance. But the killers, when they arrive, are heralded by moving POV shots straight out of a horror film.

What Red’s in fact setting up here, however, is pure noir: Travis, witness to a mob killing, is under protection by the FBI – but not for long. With a burst of gunfire, Cohen (Roy Scheider) and Tate (Adam Baldwin) arrive to escort the boy to Houston, where their bosses “want to talk to him”. The rest of the film, until its brutal dawn finale, plays out during the overnight drive, as the two killers get increasingly on each other’s nerves, until Travis eventually drives a wedge between them.

Then 55, Roy Scheider is perfect casting as the hardened pro Cohen, who tells his partner he’s been doing this job for 30 years; you just have to look at that Mount Rushmore profile to know what he’s been through. But Red also gives Cohen two deft humanising touches: a hearing aid – the only sign that he’s slowing up – and an envelope, pre-addressed to “Pamela Cohen”, which he fleetingly unfolds, fills with cash and mails when it’s clear the job is going bad. (If only someone had filmed one of Richard Stark’s Parker novels with Scheider back then, instead of leaving it to Mel Gibson a decade later.)

What Red also gives Scheider, of course, are some killer lines: “In this business,” Cohen tells Tate, “they don’t give you any social security and you don’t get a gold watch. What you do get one day when you’re not looking is a brief pain in the back of your head and a quick glimpse of your brains flying out before they scrape you up off the sidewalk.” In the showier psychopath role of Tate, meanwhile, Adam Baldwin (Animal Mother in the previous year’s Full Metal Jacket) holds his own, with verbal riffs – about what it feels like for bugs to hit windshields, and “why they print this shit they got on matchboxes” – that beat Tarantino to the punch.

In 1992 America wasn’t ready for Reservoir Dogs, which only took $2 million on its original big-screen release; four years earlier, it was even less ready for Cohen and Tate, which took a fraction of that. As a result, Red’s film went straight to video in Britain – though there was enough of a buzz about it for the Everyman Cinema in Hampstead to resurrect it for a brief run in 1989. And VHS is where it has remained – to my knowledge there has been no DVD release, though the Screen Archives label in the US apparently has one in the works, hopefully complete with the bloody final shootout heavily cut on the film’s original release.

Kathryn Bigelow, with whom Red went on to write the worthwhile feminist cop movie Blue Steel (1989), is now an Oscar winner. Tarantino is a brand. Even Adam Baldwin has a cult following for his TV roles in Firefly and Chuck. But what of Eric Red? I kept the faith through his second film as director, Body Parts (1991), a hokey Boileau-Narcejac adaptation featuring an unlikely but chilling turn from British thespian Lindsay Duncan as a sinister surgeon; and through The Last Outlaw (1993), a western he wrote for television, in which the then out-of-fashion Mickey Rourke effectively blurred the boundary between gunslinger and serial killer.

Since then Red has worked only intermittently, as writer-director of one TV film (Undertow, 1997) and two low-budget horror features (Bad Moon, 1996 and 100 Feet, 2008). I haven’t seen any of those, but the fact that Undertow stars Lou Diamond Phillips and Bad Moon Michael Paré gives the impression that Red’s talents have been underused. He turned 50 in February. Let’s hope there’s a late Red flowering still to come – profondo rosso, if you like.

“Eric Red scripted The Hitcher and co-scripted Near Dark… however this film owes a more direct allegiance to the crime movie than its predecessors, with specific echoes, in the eponymous partnership between the grizzled veteran and unstable subordinate, of Don Siegel’s The Lineup and The Killers, while the brevity of running time, compact narrative and minimal exposition summon up the spirit of bygone B-pictures”

— Tim Pulleine, Monthly Film Bulletin, June 1989

“Despite tight scripting, occasional violence and some tense scenes, this pic... is too much of a one-situation story to hold interest to the end”

— Variety, 19 October 1989

Days of gloury: Quentin Tarantino talks to Ryan Gilbey about Inglourious Basterds (September 2009)

Tarantino bites back: the director defends Death Proof in an interview with Nick James (February 2008)

Kiss Kiss Bang Bang reviewed by John Wrathall (December 2005)

The Consequences of Love reviewed by Philip Kemp (May 2005)

The Big Hit reviewed by Danny Leigh (July 1999)