Primary navigation

The Mist in the Palm Trees creates a haunting found-footage montage of 20th-century history, says Michael Atkinson

Think of celluloid, or its modern bit-celled equivalent, as time, time lost but captured, present to us only as a dead poet is present through his lines. We can experience it vicariously, this chunk of time, in perpetuity.

But it is still lost – we are watching dead people, dead moments, dead lifestyles, cities that have since died and been replaced by their reinvented selves. Film, all of it, is an approximation of the time travel we cannot actually perform. Everything that is filmed is gone forever.

Which makes found-footage films double-bladed arsenals of grief – the reuse and thus recontextualisation of old film simply magnifies its remove and cuts it adrift – and which makes the rarely seen Spanish film The Mist in the Palm Trees (La niebla en las palmeras, 2006) an unforgettable song of longing. Lost after a flurry of festival showings a few years back and a limited release in Spain, this rueful, plaintive assemblage, co-directed by Carlos Molinero and Lola Salvador, uses reams of stock footage and celluloid detritus to present a discarded home movie of the early 20th century.

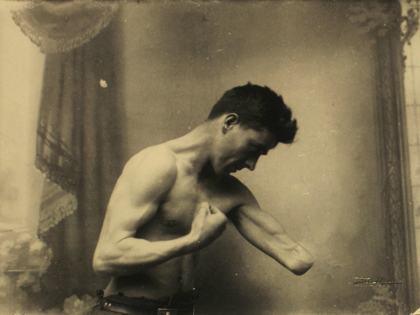

It’s also an alternate history, a fragmented biography of a Spanish physicist and photographer named Santiago Bergson (born 1905), pieced together as if from what remains of his haywire memory waves (his hushed narration is spoken by a woman, even more mysteriously), which can only recall “the photos” with certainty. Several of these are repeated so often we question what they mean: four suited men standing by a car, a nude woman with apprehensive eyes. Other images are beautiful in their agedness, as well as disturbing: child funeral portraits, coated men dancing strangely on lawns, bloodied bodies haphazardly captured after any number of atrocities. Mostly, we receive a cataract of old, oddly resonant film clips, antiquated home movies scrambled with rough news footage from the Spanish Civil War and World War II, corpses and battles, men in hats and mushroom clouds.

The montage is indeed fragmentary, repeatedly short-circuiting, seething with shadows and out-of-control emulsion entropy. Is it a fake doc, or a simulacrum of consciousness? The thrust of the vaporous story revolves around Bergson’s role in the civil war, the efforts of both the Allies and the Nazis to shanghai him into working on their respective bomb projects (“Heisenberg needs you!” declaims a four-language title card), his eventual role in the Manhattan Project, and his disappearance soon thereafter. Did he die, and when? The filmmakers muddy their pool even further with new film ostensibly shot in 1982 of three ageing women (in Spain, Cuba and Normandy), each claiming to be Bergson’s surviving daughter and mourning their father’s memory at three different graves.

Bergson is a fiction, of course, and The Mist’s drift towards documentary tropes are more dreamlike than concrete. The filmmakers call it the first “quantum” film, and it’s certainly a new kind of feature – as tentacled and historical as Craig Baldwin’s found-footage films, but swapping his sardonic impishness for a grave, melancholy search through decaying cultural remnants. It means business, emotionally and philosophically. But for a certain type of cinephile, all found-footage films come loaded with elegiac pathos by their very nature; it’s a function of film itself.

Like Bruce Conner, and Oleg Kovalov in his debut Garden of Scorpions (1992), Molinero and Salvador temper instant wistfulness with instant irony, cutting from a jerkily freeze-framed home-movie portrait of a three-year-old girl to a masterfully edited sequence in which Bergson (mostly offscreen, but also represented by a bespectacled nerd-hero in an unnamed silent thriller) is chased by the Nazis while boarding a train with a resistance fighter to escape Europe. Comprised mostly of travelogue footage and wartime newsreel stuffing, it’s the unlikeliest of poundingly thrilling chase scenes, scored to a techno beat. The movie’s soundtrack is a mini film in itself, ranging from Handel, Górecki and Angelo Badalamenti via sudden gear changes into the roar of thrash metal.

It wouldn’t be difficult to thrill to Molinero and Salvador’s film just for its evocative excavations and juxtapositions, its yearning to fathom a family that has disappeared into the folds of history. But the essential slippage of photographic ‘truth’ is very much the core of the movie’s questioning, including a disarming semi-secret story tangent revolving around doctored photos that vanish a man’s arm, and therefore save him (or not) by way of a second identity.

Despite our attention-deficit desire to see something new every moment, The Mist in the Palm Trees proves what many filmmakers, particularly Ozu and avant-gardists such as Warhol and James Benning, always knew – that the more you look at a single image, in one long viewing or in returning glimpses, the more mysterious it becomes. The nude woman, amid a slew of other strangely chaste nude studio shots, looking out at her photographer and/or husband and also looking out at us, becomes a totem for everything that has been lost unnaturally in the course of 20th-century madness. Perhaps inevitably, the film’s final coda is a wholesale dissolution into nitrate self-destruction – there are people somewhere in the frantic bacterial collapse of the imagery, but they are just beyond our vision, unremembered ghosts receding from view, behind a veil of decomposition. Time, in other words.

Whether or not Molinero and Salvador’s movie travels in particles and waves, and therefore can be read as meaningfully quantum, it remains a bewitching probe into questions every movie would raise if history was as much of a priority for us as ephemeral entertainment. And yet ephemerality is the ghost in the machine, the tragic heartbreak of the artform we had so hoped could battle mortality.

A region-free DVD of ‘The Mist in the Palm Trees’ can be ordered direct from the producers at brothers@lasaulas.net

“A fiction film composed entirely of miscellaneous found footage, The Mist in the Palm Trees purports to tell the story of Santiago Bergson, writer, physicist, and sometime pornographer who sold arms to the Resistance in France, flirted with the Nazis, collaborated on Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds broadcast and helped build the A-Bomb. Unfortunately, Carlos Molinero and Lola Salvador’s execution of their high-concept collage falls far short of its initially intriguing premise. Partially narrated by ‘Bergson’ himself in a woman’s voice, the disjointed mock biography is picked up by three different women in three different locations, all supposedly portraying the same daughter. At first, the film’s borrowed imagery convincingly captures fragmentary afterimages of the past, forging fascinating floating links between politics, physics and phenomenology. But in the absence of a strong structure, chaos finally takes over.”

— Ronnie Scheib, Variety, June 2006.

The old soldier: Gabe Klinger jump-cuts through key moments in Jean-Luc Godard’s life (August 2011)

What time is it where?: Christian Marclay talks to Jonathan Romney about The Clock (May 2011)

London’s burning: Frances Morgan on a screening of Louis Bernassi’s burning-building montage Black Umbrella (February 2011)

The Miners’ Hymns reviewed by Nick Bradshaw (July 2010)

Muck and brass: Bill Morrison and Johánn Johánnson talk to Nick Bradshaw about their archive-remix tribute film The Miners’ Hymns (July 2010)

We have always recycled: archivist Rick Prelinger on the rise of ‘archive fever’ (March 2010)

I, a man of the image: Jean-Luc Godard talks to Michael Witt about Notre musique (June 2005)

Decasia reviewed by Tony Rayns (December 2003)