Primary navigation

Having discovered a goldmine of original footage of the Black Power movement in the archives of Swedish television, documentarist Göran Olsson has crafted it into a remarkable document of the times, says Mark Sinker

Literacy and education, argues Emmanuel Todd in After the Empire: the Breakdown of the American Order, are of course essential to the rise of democracy, equality and justice. They’re also vectors, initially, of traumatised conflict, anxiety and rupture. “The move into modernity,” Todd writes, “is frequently accompanied by an explosion of ideological violence.” It’s a general historical point – he’s likening the recently turbulent Islamic world to Europe during its religious-war phase – and he doesn’t specifically discuss the black experience in America.

Göran Olsson’s documentary The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 does, of course. Indeed some have suggested that this astute tapestry of the Swedish news footage of the time, recut to sketch the tale of the Black Power movement against present-day commentary from participants and younger sympathetic observers, doesn’t do enough to set the tale in a wider context, let alone establish any kind of balanced ledger of success or failure.

This may be true; the film doesn’t editorialise, achieving perspective largely tonally, as the black-and-white footage of the first half – with its sense of the shock of change unfolding – shifts to washed-out, downcast, almost autumnal colour footage in the early 1970s, as drugs seem to flood out radical politics, and the potential for high-speed transformation shifts into impasse and bitter comedown. But by resisting the impulse to let present-day moralists tamp the story into safe hindsight shape (the younger rappers attempt a light dusting of this in the commentary) it allows us to glimpse rawer and more remarkable elements of mutual transformation in real time – the before and after of events new under the sun, that can only happen once.

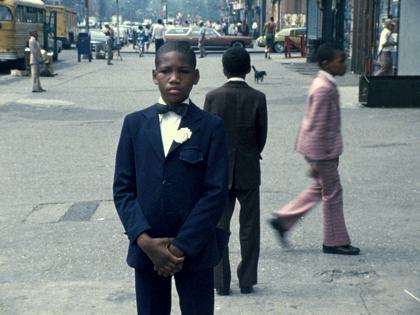

In particular, of course, we’re seeing black faces – suddenly no longer just as entertainers, but as participants given serious political weight – entering high-tech media just as this media itself arrived at the extraordinary, charged transition to global reach and interplay. There’s something exhilaratingly, even overwhelmingly emotional and disorientating in this sense of encounter during crisis: the discovery of injustice everywhere, far beyond one’s own community, and the possibility of unprecedented cultural and political identification, as traditional American modes of expression (the cadences of the black church in particular) expand to encompass the many jargons of international and third-world Marxism and anti-colonialism, from Marcuse to Fanon and beyond. And the people of the world beyond – specifically the Swedes, perhaps as naive about America as America is unaware of them – gaze back, and bring their own quiet presence to bear.

In 1964, as part of his rigorous self-education, Malcolm X journeyed to the Old World to study Islam. Until just before that time, he had been the anointed spokesman of Elijah Muhammad’s US-based Nation of Islam (NoI), but in Africa and the Middle East he discovered no reverence for and little interest in his erstwhile mentor. Already at odds with the NoI, Malcolm now began to become at once more orthodox in his religion and more internationalist and confrontational in his politics. The consequence, in 1965, was his assassination by members of the NoI (though many saw the hand of the US government in the act).

Indeed it seemed to be open season on black leaders and communities: from Medgar Evers, murdered in 1963, to Martin Luther King in 1968. King, of course, had developed the strategy of non-violence, but many younger black voices began arguing that a purely non-violent response no longer made sense. In 1966 Huey Newton and Bobby Seale had set up the Black Panther Party for Self-Defence in Oakland, California – “self-defence” meaning they were armed. Stokely Carmichael, chairman of the Student Non-Violent Co-ordinating Committee, was popularising the term “Black Power”; and as Mao had noted, political power flows from the barrel of a gun.

This is the backstory; and intricate as it is – awareness of the intense tactical differences and factional rivalries involved would take pages to detail – viewers of The Black Power Mixtape are expected to supply it for themselves. Right at the start, one Al, owner of a small Florida-beach burger joint, exclaims that Americans are better off than anywhere else in the world, and this is very nearly the last white American voice we hear. The documentary offers a view of a movement from within itself – albeit an intensely divided movement, led by eloquent, charismatic, often contradictory people. But divisions and contradictions are not dwelt on; it’s not always clear if the filmmakers who shot the footage were aware of them at the time.

Eldridge Cleaver

What the film can offer are those glimpses of key moments of transition: for example the moment when the young Carmichael, serious yet gentle, decides to take the microphone from a Swedish interviewer to coax the most potent story from his own mother. Or at a press conference in Stockholm, where journalists are asking him if he’s afraid of jail. “I was born in jail,” he quips, a spur-of-the-moment invention, and then widens his eyes and purses his mouth at them, as if to say, “What d’you think of that!?”

No one had been a better, smarter student than Angela Davis: she’d travelled widely in Europe, and a place in the elite was hers for the taking. Yet in 1970 we’re watching her interviewed while on trial for her life, after she bought the gun used in the kidnap and murder of a judge. Pale, exhausted, frightened, yet alertly articulate, she responds to a Swedish question about violence, at first with sardonic exasperation and communist cliché.

But then, as she casts about for an argument more fit for the situation, she plunges back into her own history: back to Birmingham, Alabama in 1963, and the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church. Four small black girls, girls she knew personally, were blown to pieces, “limbs and heads strewn over the place”. And yes, the local black community armed itself as a consequence. You hear the shift in her voice as she recounts the change in her community, the decision made. You can trace the logic to Mao, or to the Second Amendment to the US Constitution – the right of all its citizens to own and bear arms. But chances are this is a kind of moralising also: the muffling hindsight that obliterates the filmmakers’ camera-captured instant.

Obliteration is what the final quarter of the film mainly shows, perhaps in spite of itself. It’s dominated by an extended 1974 interview with Louis Farrakhan, Elijah Muhammad’s successor (and, many believe, the man who ordered Malcolm X’s killing). Farrakhan’s a silky and energised charmer, whose quasi-religious will to outrage (“the white race is a race of devils”) seems a dogmatic world away from 1967, a shutdown into narrow parochial and reactionary certainty.

The NoI brought discipline – and an escape from the drugs that flooded the ghetto. But the cultural pride they enforced – hostile to all curiosity, to any non-sanctioned learning – is just a step away from self-loathing; it’s far more about fear than courage. The most heartbreaking image of all here, however, is about both: a teenage junkie prostitute that same year telling the camera, firm of voice but through a film of tears, that she thinks she can make it. Did she, you wonder?

“The most dangerous creation of any society is the man who has nothing to lose,” James Baldwin famously wrote, and the wisdom of that argument suffuses this documentary. Carmichael would flee into exile and there, as a guest of one of Africa’s mid-rank pseudo-Marxist dictators, become a sometime apologist for a mirror-image oppression – another end-of-arc that’s beyond this film’s scope.

“It’s not about black and white,” comments R&B singer Erykah Badu towards the end of the film, “it’s about the story. We have to tell the story right. And that’s why we as black people have to document our own history – or the history becomes twisted. We get written out.” There’s an irony here – involving non-black Swedes – but everyone involved is quietly aware of it.

Göran Olsson talks about the construction of The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 on page 51 of the November issue of Sight & Sound

Fight for rights, will to power: Greg Tate on the struggles for black equality and identity in The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 (October 2011)

The land still lies: Mark Fisher on John Akomfrah’s Handsworth Songs and this summer’s English riots (September 2011)

Egypt’s revolutions on film: Omar Kholeif looks back at representations of nationalist revolution in Egypt’s cinematic history (July 2011)

Lost and forgotten: Mark Sinker on the ‘forgotten films’ of Britain’s late 1960s and 1970s cinematic watershed (July 2010)

We have always recycled: Rick Prelinger sketches an alternative history of the rise of ‘archive fever’ (March 2010)

Not forgotten: Adania Shibli on Sarah Wood’s For Cultural Purposes Only and the memory of the Palestinian Film Archive (November 2009)

Be black and buy: Ed Guerrero on the 1990s mainstreaming of black American cinema (December 2000)