Primary navigation

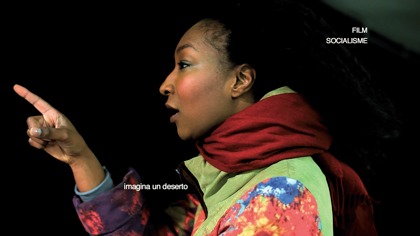

More than half a century after Breathless first catapulted him on to the world stage, Jean-Luc Godard is still challenging cinematic norms with his politically charged, poetic essay Film Socialisme. Gabe Klinger jump-cuts through key moments in the director?s life

An elder statesman of far-left cinema, 79-year-old Jean-Luc Godard appears at the Cinéma des Cinéastes in Paris to do a Q&A after a screening of his latest work, Film Socialisme. The filmmaker is puffing away at a cigar, and moderator Edwy Plenel warns those of us in attendance, “Even though Mr Godard can smoke, you cannot.” It’s a small detail, but one that reminds the audience that Godard hails from another era. Nouvelle vague luminaries Luc Moullet, Agnès Varda and Jean Douchet are present. The reverence in the room is high. A long time ago, the men in the cinema would have removed their caps.

Godard’s films, like the individual, occupy an enduring place in the discussion of cinema in the last half-century. Breathless (A bout de souffle, 1960), the film that catapulted the director on to the world stage, celebrated its 50th anniversary on the eve of Film Socialisme’s unveiling. If one didn’t know Godard’s vast filmography, encountering the new film would not lead one to the conclusion that it was the work of a septuagenarian. Film Socialisme is an unconventional essay-narrative-poem that plays boldly with digital aesthetics, and on this particular evening Godard is animated as he discusses it. He honours audience questions for nearly two hours, makes jokes…

Roughly a month earlier, at the world premiere of Film Socialisme in Cannes, the filmmaker had declined to attend, cheekily citing “problems of the Greek type” as justification. A frustrated press corps took this personally, conflating the perceived above-it-all attitude of Film Socialisme with that of the author himself. In Paris, though, Godard proves the opposite: he’s discursive, vulnerable and never taunting or condescending to the eager listeners in the cinema.

Outside the hostile context of Cannes, where hasty evaluation takes precedence over thoughtful analysis, the film reveals the same generosity of spirit and openness for debate. Godard’s dense assembly of history in Film Socialisme – encompassing everything from the Bronze Age to the Spanish Civil War to the current economic crisis – is not to be unpacked without some work. (For a full appraisal and synopsis, see Brad Stevens’s review in S&S August 2011.) Indeed, for those not versed in Godard’s disjointed style of cinema, in the essay-film genre as exemplified by filmmakers such as Alain Resnais, Chris Marker, Jean-Daniel Pollet and Varda, or in the grand arc of 20th-century geo-politics, Film Socialisme may appear inscrutable.

Breathless

Barely known, 19-year-old cine-club regular Jean-Luc Godard pens an article for the Gazette du cinéma titled ‘Towards a Political Cinema’. It’s the earliest evidence of his fixation with politics vis-à-vis film. In the piece, Godard sorts through his feelings having just viewed a scene from a Gaumont newsreel on a May Day rally. Watching this brief fragment, he understands the potential of a propagandistic film language, capable of seductively thrusting the beautiful bodies of young German communists through time and space in the name of a larger cause. It’s an enigmatic piece (not uncommonly for Godard at this early stage of his career) and one that ends by pointing a finger at “unhappy filmmakers of France” for not making issue-oriented films, as if to dare them.

Unlike his contemporaries Jacques Rivette and Eric Rohmer, who were never as explicitly political in their own critical work for the Gazette (and later for Cahiers du cinéma), Godard gradually revealed from that point on a vigorous engagement with the issues of the day, from the Algerian War in his second feature Le Petit soldat (1960) to Vietnam in a number of films at the end of the 1960s. Godard would go on to say in an interview, “The nouvelle vague is accused of showing nothing but people in bed” – an indictment that could extend to the author himself; the longest scene in Breathless depicts its two leads arguing in bed. However, the filmmaker went on to assure us, “My characters will be active in politics and have no time for bed.”

Night and Fog (Nuit et brouillard, 1955), one of the first analytical films on the horrors of the Nazi death camps, is announced for Cannes. It’s a pivotal moment in the evolution of the essay film as a subgenre. Resnais, the director, lends aesthetic rigour to a subject of meteoric importance, once again confirming the lofty position of cinema as a tool for the dissemination of documented history.

Night and Fog

Unlike documentaries before it, Night and Fog is an assemblage of found footage from the war and present-day material shot by a professional crew; in addition, novelist Jean Cayrol, a survivor of the Shoah, is involved as screenwriter, affording the film its passionately motivated agenda: history must not repeat itself. By the time Godard embarks on Histoire(s) du cinema (1989-98), an eight-part culmination of his preoccupations with the history of art and world politics and their intertwined relationship with cinema, he has fully internalised Resnais and Cayrol’s gesture and laments the present day’s capacity for cultural amnesia. Making the spectator complicit, Godard declares, “You saw nothing at Hiroshima… at Sarajevo” – thus bringing 20th-century history full circle.

In a two-minute tour de force deconstructing a single photograph from the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina entitled Je vous salue, Sarajevo (1993), Godard narrates a poetic voiceover that offers a condensed formulation of his main preoccupations. “There’s a rule, and an exception,” he informs us. “Everybody speaks the rule: cigarette, computer, T-shirt, television, tourism, war. Nobody speaks the exception. It isn’t spoken, it’s written: Flaubert, Dostoevsky. It’s composed: Gershwin, Mozart. It’s painted: Cézanne, Vermeer. It’s filmed: Antonioni, Vigo.”

In Film Socialisme, “the rule” is the subject of the film’s first part: a giant tourist cruise liner with a trajectory beginning in the cradle of civilisation (Egypt, Israel, Palestine), continuing into Europe (Greece, Italy, Spain), with an odd excursion through the Black Sea (Ukraine). The various characters intersect in gyms, casinos, dining rooms, nightclubs, tacky art galleries and even something like a makeshift Christian prayer room adjacent to slot machines. Evidently for Godard, “the rule” is the detritus left as mankind unthinkingly consumes each landscape it disembarks on.

The depressing reality of the cruise is sharply contrasted with “the exception”: brief glimpses of humanity’s glories (and some of its follies), represented mainly through film clips, paintings, classical music and passages from literature – the core materials of Godard’s densely layered video essays starting in the mid-1970s. Godard’s assortment of formats amounts to a satisfying whole: none of the three parts of Film Socialisme isolates a particular stylistic device in favour of another. The narrative in Godard is fully complemented by essayistic digressions; where literature had embraced such modernist complexity in the likes of Joyce and Beckett, earlier 20th-century cinema had not. Film Socialisme, interestingly, arrives at the intersection of the maturing film-essay format and the transformation of our visual culture through the new digital means of communication.

A date of paramount relevance in Film Socialisme: the start of the mutiny aboard Imperial Russia’s Potemkin battleship. This incident forms the basis of Eisenstein’s fictionalised Battleship Potemkin (1925), which Godard amply samples in Film Socialisme (as he had before in Histoire(s) du cinéma). The concept of a dramatic recreation building upon, distorting or substituting the memory of a real event is not of particular interest in itself. According to art critic Harold Rosenberg, who was cited by Godard in his 1950 article, it’s the manifestation of the consciousness of self that reveals how artists engage “in the drama of history through the spontaneous and passionate poetry of the events”. This might help to explain why the action on the Odessa Steps, as visualised by Eisenstein, is better known – and more methodically studied – than anything that actually happened in the moments after the sailors aboard the real Potemkin rebelled. This, ultimately, is a Bazinian ideal of cinema come to fruition, one that Godard repeatedly attempts to demystify in his video essays.

The Last Bolshevik

However, Godard is also taking a cue from an earlier example of the essay film, Chris Marker’s The Last Bolshevik (1993). In a film that examines the history of the Soviet Union through its propaganda machinery (anchored by the life of filmmaker Alexandr Medvedkin), Marker offers a memorable sequence in which he measures the physical length of the Odessa Steps, remarking that it would take a few short minutes to descend them in real life; Eisenstein manages to extend the action considerably – and to great dramatic effect – in Battleship Potemkin’s most celebrated sequence. Again, it’s not a particularly revelatory observation. But a savvy essayist like Marker knows that to emphasise such a detail will take the viewer from a passive into an active viewing mode, where every subsequent image may be scrutinised for its manipulative placement.

Godard – like Marker – does not wish to manipulate the viewer, instead presenting every scene, every historical detail as if it were a splinter to be added into a larger body. This patchy style attempts to approximate historical memory as a shattered mirror. Remarkably, Godard sees an aesthetic potential in the poetic grandeur of this impressionistic concept. While his political stances may at times appear well worn in their didactic effect, his presentation is anything but academic. His detractors, however, see Film Socialisme as frustratingly cryptic.

Assertion is not Godard’s strong suit. His films may be stylistically confident, but they highlight ambiguity and champion individual freedom over the interest of states. (“The dream of the state is to be one. The dream of the individual is to be two,” is one slogan presented in Film Socialisme.) After three years of censorship woes owing to a controversial torture scene, Le Petit soldat – his first feature after Breathless, and his first immersion into the political arena – finally enters Parisian cinema in the autumn of 1963. (Godard has shot another four features in the interim.)

Le Petit soldat

In the film Godard creates one of his most complex characters, Bruno Forestier (Michel Subor), a right-wing French terror agent caught up in the struggles of the Algerian War, who ruminates his doubts in voiceover and acts in a paradoxical, not always implicitly self-serving manner. In Cahiers du cinéma, critic Jean-Louis Comolli sharply observed: “Forestier, in order to find himself, must keep trying to escape from the ready-made solutions and constraints of his ‘friends’ as well as his ‘enemies’, from the warring parties, the contradictions that surround him… So if the little soldier seems to be alone in a purely personal combat, spectators, in defining themselves vis-à-vis a party, a point of view or a political stance, are putting themselves on the same level as the terrorists in the film… Supreme irony of mise en scène, to render on the judge his own verdict.”

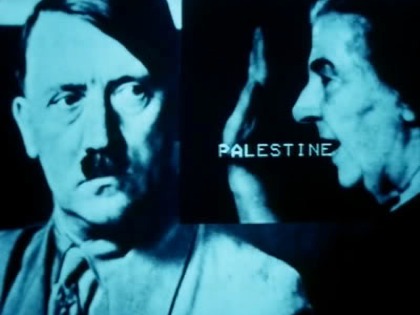

Carrying a part of Forestier within him, Godard never dares to be persuasive on purely political terms. In Film Socialisme, the words “State of Palestine” in Arabic are superimposed over the word “Palestine” in Hebrew. This title appears as a cryptogram to those who speak neither language – and yet, decoded, it’s almost unbelievably simple in its didactic value.

Finally, is it possible to discern a political bias in Godard? A number of events often overlooked by commentators who would prefer to see Godard as an armchair radical or a grumpy anti-Zionist (on this score, Godard’s interview personality is more problematic than the work itself) make it difficult to reach a conclusion.

Contacted by the Arab League via Hany Jawhariyya – the official filmmaker of Arafat’s Fatah party – Godard, co-director Jean-Pierre Gorin and cinematographer Armand Marco had set off in 1969 on a project to make a film in Palestinian camps in Jordan, the West Bank and Lebanon. Godard had jumped head first into political filmmaking with the Dziga-Vertov collective, which aimed to redefine the method by which political films were made and distributed. The Arab League’s proposal had taken the three filmmakers decidedly out of their comfort zones. Spending close to nine months travelling through the Middle East, Godard, Gorin and Marco had accumulated 40 hours of rushes and, by the end of August 1970, were prepared to begin editing their most ambitious effort to date.

And then the events of Black September happened: a spate of hijackings, followed by the Jordanian government’s savage crackdown on Palestinian organisations.

Godard and Gorin were already deeply conflicted as a result of a problematic shoot. They had found their overall design for the project, provisionally titled Until Victory, thwarted by various location circumstances, the most troublesome being translation problems (neither filmmaker spoke Arabic) and cultural differences (women teaching themselves to read and write in the camps refused to let the crew film them, much to the bafflement of Godard and Gorin).

Antoine de Baecque, author of the recently published Godard: biographie, documents the comically short interview that Godard attempted with Yasser Arafat. Apparently, he only managed to ask two questions before the peeved leader told him to “come back tomorrow” (a second meeting never materialised). Godard’s questions to Arafat are revealing of the filmmaker’s multidimensional understanding of history, endeavouring to join the dots philosophically between the Palestinian struggle in the 1960s and 70s, and the Jewish struggle during World War II.

“I asked him if the origins of the Palestinians’ difficulties had something to do with the concentration camps,” Godard reported. “[Arafat] said to me, ‘No, that’s their story, the Germans and the Jews.’ And I said, ‘Not exactly, you know that in the camps, when a Jewish prisoner was very weak, close to death, they called him Muslim [musulman].’ And he responded, ‘So?’ I said, ‘You know, they could have called them black or an entirely different name, but no, they said Muslim, and that shows that there is a relationship, a direct relationship between the Palestinians’ difficulties and the concentration camps.’” Godard proceeded with a more conventional line of questioning before Arafat curtailed the discussion. (I offer this anecdote in its entirety as some corroboration that hysterical accusations of Godard being anti-Semitic are misguided, especially in relationship to the nuanced Israeli-Palestinian situation as it’s presented in Film Socialisme.)

Ici et ailleurs

These occurrences couldn’t help but fuel a growing ambivalence on the part of Godard and Gorin. To paraphrase de Baecque, was Until Victory to be a work of mere propaganda, or an informed critique of the methods of the Palestinian resistance?

But by mid-September 1970, a great number of the people filmed by Godard, Gorin and Marco have been massacred, imprisoned or dispersed by King Hussein’s army in an effort to expunge the Palestinian liberation movement from Jordan. The filmmakers’ wish to show the first cut of the film to the subjects is now a tragic afterthought.

Throughout the month of September, Godard and Gorin remain barricaded in their editing suite for fear that they may be the targets of Mossad, Zionist militants or the Jordanian secret service. These circumstances shake Godard to his core. The dissolution of the Dziga-Vertov group becomes inevitable. (Later, in 1976, the material from Until Victory will be reshaped with help from Anne-Marie Miéville into Ici et ailleurs, one of Godard’s best and one of the most astounding essay films ever made.)

Film Socialisme premieres in Cannes. When Godard’s cruise liner attempts to dock in Palestine, the words “ACCESS DENIED” flash on the screen. A day earlier, activist Noam Chomsky, a Kibbutz member at Israel’s infancy, has been barred entry to Israel. Small coincidence, big irony.

In the year since then, the Arab Spring has happened, Spain has joined Greece as a beleaguered economy, the Italian government has been facing increasing scrutiny, and France has banned the wearing of burkas (among other alarming trends in the Right). Film Socialisme’s tableau expands every day, Godard’s shattered mirror reassembling triumphantly, and lastingly, in the mind of whoever is willing to look and listen – and to engage.

‘Film Socialisme’ is released on 8 July, and is reviewed in the August 2011 issue of Sight & Sound

How they did love: director Emmanuel Laurent on his portrait of Godard and Truffaut, Two in the Wave (February 2011)

Doom, chills and bewilderment: Nick James on Film socialisme at its Cannes premiere (May 2010)

The New Wave at 50: The star reborn: Ginette Vincendeau on how the French New Wave transformed the nature of film stardom (May 2009)

Riding the wave: Six renowned directors on what the New Wave meant to them (May 2009)

Breathless reviewed by Tim Lucas (December 2007)

I, a man of the image: Michael Witt interviews Jean-Luc Godard (June 2005)

Éloge de l'amour reviewed by Keith Reader (November 2001)

Paris match: Godard and Cahiers: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith on the post-war Parisian fun and ferment that produced the New Wave (April 2001)