Primary navigation

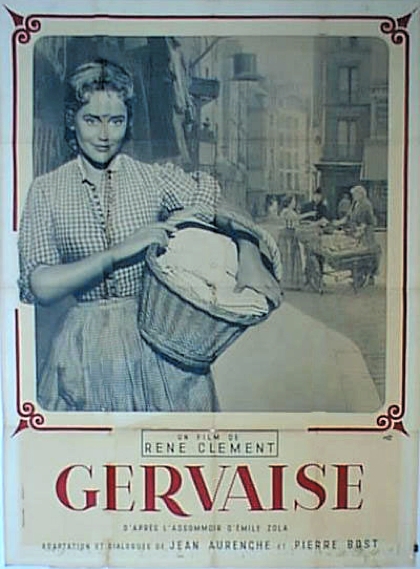

Mark Le Fanu pays tribute to 1956’s Gervaise, a great example of Zola on film – and of the work of its neglected director, René Clément

Emile Zola has been well served by the cinema, not merely in the number of adaptations that have been made from his work, but also in their quality. Back in the silent epoch there was Albert Capellani’s titanic two-and-a-half-hour version of Germinal (1913), along with two further masterworks: André Antoine’s beautiful adaptation of La Terre (1921) and Marcel L’Herbier’s of L’Argent (1928). Renoir adapted Zola twice (Nana, 1926, and La Bête humaine, 1938), while the 1950s gave us Marcel Carné’s powerful Thérèse Raquin (1953, with Simone Signoret) and Fritz Lang’s Bête humaine remake Human Desire (1954). More recently Germinal has been done again, quite impressively (by Claude Berri, 1993), and doubtless there are others I haven’t come across.

René Clément’s Gervaise, an adaptation of the 1877 novel L’Assommoir, was released in 1956. It was briefly available on Region 1 DVD as part of the Janus Films’ Essential Art House collection, but is otherwise unavailable. The original book was part of the celebrated Rougon-Macquart series, in which Zola followed the fortunes of a family whose inability to prosper in the world is linked to the hereditary curse of alcoholism (l’assommoir itself means cheap drinking den). Clément’s adaptation is a masterpiece – as good an example as one can get of the ‘tradition of quality’ that exemplified post-war French cinema before it was attacked (and effectively destroyed) by the hostility of the nouvelle vague.

Zola’s story centres on a “belle Parisienne”, Gervaise – a washer-girl with a limp, played by the beautiful Maria Schell. As the tale opens she is in love with handsome wastrel Lantier (Armand Mestral) who, having bedded her, promptly deserts her. Humiliated by this public rejection, Gervaise presses ahead with her aim to open a little laundry shop of her own, aided in this ambition by a new man in her life, a roofer named Coupeau (Francois Périer). But Coupeau, initially sound and solid, is injured in a fall and, when his injuries fail to heal, takes spectacularly to the bottle. This is a cue for Lantier to move back into the household, first as a lodger and finally – as the twists of fate sap our heroine’s soul – as master and conqueror. The film ends with the establishment in financial ruin, Gervaise a penniless alcoholic and her barely teenage daughter Nana about to set off on the street to become a prostitute.

The tale, as such, couldn’t be more pessimistic. And yet a summary doesn’t communicate at all the flavour of this work of art, which is imbued with a sort of perverse gaiety or even nobility. Terrible things happen to Gervaise, yet without essentially corrupting her: she remains to the end a sweet moral being. Incarnated in Maria Schell’s vibrant and beautiful performance, the qualities that seem to define her most are kindness and optimism. In contrast to the scenes where Gervaise is victimised, there are other, equally important scenes where we see her take charge of her life: organising and running the laundry; coping lovingly with her husband’s long illness; maintaining her dignity, finally, in the face of her evil star Lantier.

In keeping with the pitiless realism of Zola’s original, Clément’s Gervaise is spiritually bold. French cinema has a reputation for dealing with sexual matters in a candid, non-prurient manner, and Gervaise is in this sense a wholly ‘grown-up’ movie adaptation, availing itself of freedoms from censorship that weren’t on offer for American or British filmmakers at the time. There’s a wonderful scene when Gervaise invites friends from the neighbourhood back to her home for a celebration dinner. A roast goose is produced and carved at the table and, while the carver is pouring juice out of the bird onto the gravy dish, one of the revellers is overheard to exclaim: “I wish my wife would piss in my mouth like that!” A proletarian robustness is everywhere in evidence, most famously in another, earlier scene showing Gervaise, victor in a titanic laundry-room cat-fight, pulling down her opponent’s drawers and slippering her naked bottom in front of the assembled washerwomen.

The dialogue throughout the movie is dark, sardonic and pithily to the point. At the party sequence there’s a pregnant confrontation in the kitchen, during which Gervaise reveals her attraction for the first time to an upright admirer. “Kiss me!” she begs him tipsily. “You’ve had too much to drink,” the man replies – not without kindness, and at any event tempted. “So have you,” Gervaise counters in sweet desperation. “That’s why we should do it!” – at which point she hurls herself into his arms. Without ever making a big deal of it, Clément’s film has a physical sparkle and a pervasive sensual undercurrent.

The acting is excellent right across the board. Hitchcock famously said that, in filmmaking, every stitch in the tapestry has to count. The minor characters in Gervaise are just as meticulously shaded as the principals: in the large party scenes, for example (the goose supper, the fight in the laundry, a visit to the Louvre) you’re made to feel that everyone in frame has a backstory. The responsibility for such effortlessly authentic evocation is primarily the director’s, but it helps in this case that the film was written by Jean Aurenche, one of the finest scenarists of the day (he worked for many years with Claude Autant-Lara and, later in his career, with Bertrand Tavernier). Credit too must be given to production designer Paul Bertrand for his beautifully detailed sets, both interior and exterior – which somehow give the impression of being genuine locations – and to the lovely, atmospheric black-and-white photography of Robert Juillard.

Gervaise was Clément’s 20th film. He was always an eclectic filmmaker with a palette that ranged from classy thrillers like the Patricia Highsmith adaptation Plein soleil (1960) to international blockbusters like Is Paris Burning? (1966), not forgetting the two strikingly contrasted films that put him on the map: La Bataille du rail (1946) and that exquisite exploration of childhood, Forbidden Games (Les Jeux interdits, 1952). Yet despite these undoubted hits among a roster of 30 movies, Clément has never ridden high in the auteurist pantheon. What does or doesn’t make an auteur is always a complicated business. But the Criterion edition of Forbidden Games resurrects two fascinating interviews with Clément in person, in which he comes across as a man with a genuine inner life: a thinker, an artist and a poet.

“René Clément has achieved a tremendous tour-de-force of literal realism. In the intimate care for every detail of streets and clothing and people, he has exactly recreated the Parisian low-life of the Second Empire… The acting is as precise and as minutely observed. Périer’s performance as Coupeau, above all, is flawless… But something is missing; and we must turn back to Zola to find just what it is… The observed surface of reality provided only one part of Zola’s work; its vitality lay in the coarse, vigorous poetic imagination which animated it, and which is lacking in Gervaise.”

— David Robinson, Monthly Film Bulletin, January 1957

A love-hate relationship: Ginette Vindendeau on François Ozon’s Potiche and the love-hate relationship between French cinema and boulevard theatre (July 2011)

This Filthy Earth reviewed by Peter Matthews (December 2001)