Primary navigation

Nick Bradshaw revisits Lionel Rogosin’s On the Bowery, a pioneering drama-doc shot on the mean streets of New York

On the Bowery / Good Times, Wonderful Times

Lionel Rogosin; US 1956/64; Milestone / Region-free Blu-ray; 65/69 minutes; Aspect Ratio 4:3; Features: introduction by Michael Scorsese, The Perfect Team: The Making of On the Bowery, A Walk Through the Bowery, Street of Forgotten Men (1933), Bowery Men’s Shelter (1972), Man’s Peril: The Making of Good Times, Wonderful Times, Out (1957)

The greatness of Lionel Rogosin’s 1956 On the Bowery, a stark, intimate and vital portrait of homeless drunks on New York’s skid row, has long been one of cinema’s open secrets. The first American film to win the Grand Prize for Documentary at the Venice Film Festival, it also garnered a Bafta Flaherty Documentary award and was nominated for an Oscar. Inspired by Robert Flaherty’s ethnographic forays, the Italian neorealists and – as its director would insist – “by life”, Rogosin’s semi-performed, minimally dramatised documentation of real people in their actual environments formed a key plank of the New York-centred New American Cinema, dovetailing with the experiments of Sidney Meyers, Morris Engel, Shirley Clarke and John Cassavetes and thus helping sire the American indie movement as well as inspiring Jean Rouch and the nouvelle vague.

Yet the film opened to dismissive reviews (“a dismal exposition to be charging people money to see… merely a good montage of good photographs of drunks and bums, scrutinized and listened to ad nauseam,” wrote Bosley Crowther in The New York Times), was allegedly repressed abroad by the US State Department, and it’s fair to say has remained under the carpet ever since. Milestone’s Blu-ray release – mastered from a restoration by the Cineteca del Comune di Bologna and the first half of a planned two-volume collection of Rogosin’s work – is the film’s first issue on home video in 25 years (outside France).

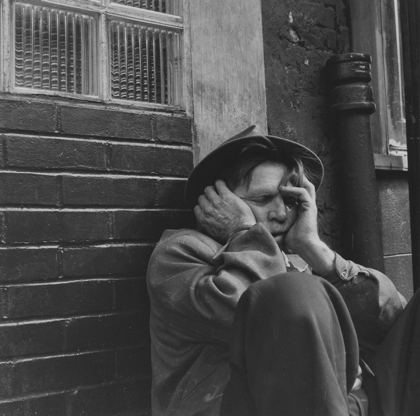

Looking the other way is, of course, the tendency On the Bowery countermands from its opening frames – expository shots of a neighbourhood in the physical and historical shadow of Manhattan’s old Third Avenue elevated rail line, the streets below littered with the idle bodies of men who typically, we learn, once worked the railroad. While police busy themselves impounding public-bench sleepers and other undesirables, DP Richard Bagley records them in gutters, in (typically bar) doorways, even reclining in a cart with a copy of Esquire. The camera follows a new arrival – the craggily handsome Ray Salyer, whom Rogosin met fresh to the Bowery after a weekend’s bender – through three days on and off the wagon, his lingering faith in temperance and gainful employment contrasted with that of Bowery lifer Gorman Hendricks, per the storyline a barfly glad-hander who comes to seem both angel and devil on Ray’s shoulders. (Offscreen, Hendricks put his death-spin drinking on hold just long enough to complete the shoot.)

Ray is the focus of a couple of long, telling set pieces in the bread-and-bed queue of the Bowery Mission and later, when his patience with its Hadean claustrophobia snaps, in a long night’s bar orgy that you’d be hard pressed to call staged. (Documenting drunks would seem to have the upside of facilitating the subjects on-camera artlessness, though the collaboration with them seems to have spurred Bagley to an early boozy grave too.) The plotline lends the film a depth of characterisation and soul, but Rogosin is careful never to narrow his angle; in bars and on the street, the film inscribes, in crisp, luminous monochrome and sometimes less lucid sound, the bacchanalian faces and voices of an entire demimonde. Rogosin talked of making a film “close to painting and sculpture”; in a making-of on this set, the scholar Ray Carney cites the Rembrandts on the director’s New York apartment walls as a model for the photography.

Rogosin’s solidarity with these down-and-outs may partly have derived from the WWII naval service he shared with many of them; more likely it was innate. The son of an émigré New York textile tycoon, he quit his father’s business to take aim at the worldly maladies he’d seen in the war: “We just came through the Holocaust, which was insane. Something’s wrong. I have to find out – with my camera.” On the Bowery was intended as a trial run for his smuggled 1959 apartheid exposé Come Back Africa, which will presumably headline Milestone’s second Rogosin set. This volume’s extras include the aforementioned plain-but-useful making-of, a Martin Scorsese introduction, three shorts depicting the Bowery in 1933 (Street of Forgotten Men), 1972 (Bowery Men’s Shelter) and now, and two other Rogosin films.

Out (1957), a melancholic 25-minute portrait of refugees from Hungary’s crushed 1956 revolution, supervised by Thorold Dickinson for the United Nations Department of Public Information, shares with On the Bowery a palpable sense of unwillingly idle masses stuck in time (and likewise asks us to share their inertia, withholding much of their backstories to the end).

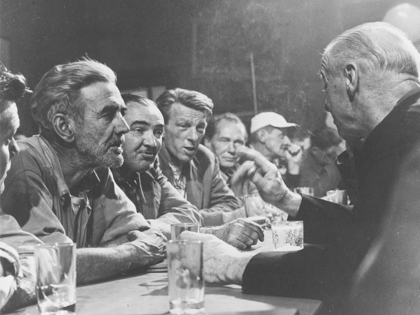

Swapping sympathy for satire, and subtlety for primal scream, Rogosin’s third feature Good Times, Wonderful Times (1964) watches the booze flow once more at a horrendous Swinging London cocktail party whose braying, shallow and occasionally charming guests – culled mostly from ad land, according to its editor Brian Smedley-Aston – vent varieties of smug prejudice about the virtues of war, while Rogosin intercuts extended scenes of horror from WWI, the Warsaw Ghetto, the Eastern Front and Hiroshima, as well as anti-war protests in Japan, Washington and Aldermaston. Watching it, you pine for the poetry of Hiroshima mon amour or Simon of the Desert and suspect that, without certain constraints, Rogosin would have mercilessly continued adding scenes ad infinitum. But that may be the point.

On the Streets reviewed by Edward Lawrenson (November 2010)

Street fighters: Dylan Cave talks to Joseph Bull and Luke Seomore about Isolation, their documentary about homeless British ex-servicemen (July 2010)

Open Ear Open Eye: Tom Charity on John Cassavetes’s Shadows (March 2004)

Supertramp: Paul Merton on Charlie Chaplin (October 2003)

Lilya 4-ever reviewed by Tony Rayns (May 2003)

Boudu Saved from Drowning reviewed by Tom Milne (Monthly Film Bulletin, November 1965)