Moving At The Speed Of Emotion

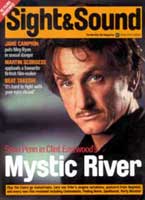

Scorsese discusses a favourite Brit director with Philip Horne, who reviews Dickinson's career

Thorold Dickinson (1903-1984), whose centenary falls on 16 November, hasn't been remembered as widely or as well as he deserves. A conference in London in October, a screening of his greatest film The Queen of Spades (1949) at the London film festival and a season of his films at the National Film Theatre starting in November, not to mention the issue of The Queen of Spades on DVD in the US, should put him back on the map.

Still, Dickinson has had his constant supporters. When Martin Scorsese received a bfi fellowship in 1995 his acceptance speech mentioned his enthusiasm for Dickinson's films, which prompted me to approach him on the subject. After some years of letters and talks, and much kind help from Thelma Schoonmaker, he generously found time to answer some questions during the shooting of The Aviator in August 2003.

Philip Horne: What do you find most striking about Thorold Dickinson as a film-maker?

Martin Scorsese: There's a sense of adventure in the overall arc of his career. He didn't make many films, but each is a fascinating project. Even when the movie doesn't work, like Men of Two Worlds or The Prime Minister, you're struck by the choice of subject matter, by the vivacity of the film-making, the intelligence of the approach. The idea that there was a heavily French side to Dickinson seems right to me. The eye for small, homespun details, the concentration on the gestures of the actors and the interactions between the characters feel close to Renoir. Also, Dickinson is never afraid to push the emotion in a scene, and that's rare in British film-making, even with film-makers like Robert Hamer or Carol Reed. Whether it's through the editing (The Arsenal Stadium Mystery) or the acting (Anton Walbrook in Gaslight and The Queen of Spades) or the lighting and decor (The Queen of Spades) or a combination of the three, Dickinson puts the emotions of his characters at the centre of the movie. And there's a nervous energy in his movies that's very unusual. They really move.

Do you have a favourite Dickinson scene?

The flashbacks in The Queen of Spades are extraordinary. And the scene where Edith Evans dies the way she looks Walbrook in the eye with that blank expression is unforgettable. It's completely ambiguous, which is what makes it so frightening she could be terrified, she could be transferring her 'sin' to him, she could be secure in her own evil: you don't know, and neither does he. It's easy to imagine many other film-makers turning it into a superficial frightfest.

How highly would you rank Dickinson's films?

The Queen of Spades is a masterpiece that ranks right up there with the finest films of the period. Gaslight is also one of the strongest films of the 1940s, British or otherwise. (It's interesting he had only three weeks to prepare Gaslight, and only three to four days of preparation for The Queen of Spades!) And Hill 24 Doesn't Answer is a unique film. In British cinema Dickinson is certainly one of the most ambitious and talented film-makers of his time.

Is there a case to be made for 'The High Command'?

The High Command is quite striking considering it was obviously made on a low budget. And I would have to agree with Graham Greene's assessment of the 'God Save the King' scene it's the most remarkable thing in the film. A group of colonials, who are very uneasy with one another, suddenly stand still for the anthem while a storm practically blows the room apart and the native help scurries around to keep everything intact. There are many fascinating moments little inserts and bits of business where a sense of cultural conflict is woven into the action. Dramatically it's not really part of the story being told, but the way Dickinson films it, the colonial world of West Africa starts to seem enclosed, cut off. There are many melodramas of the period with this kind of 'stiff-upper-lipness', and it's here in Lionel Atwill's acting in particular. But the subtlety of Dickinson's approach to colonialism gives the stoicism an extra edge. And as always with Dickinson, it's underscored by passion Atwill's love for his daughter, James Mason's love for the trader's wife.

Do you think 'The Arsenal Stadium Mystery' measures up against English Hitchcock or against the 'Thin Man' films?

It's a slight, B-movie murder mystery, more of a 'quota quickie', so it's not really fair to compare it to the English Hitchcocks. But it's a lot of fun, and there's something in the breeziness of the Leslie Banks character the hats he wears, the way he's worried about closing the murder case before the stage show in drag down at the police station that seems close to the Thin Man films. There's a great moment just before he finds the incriminating piece of evidence, where he says, "Oh, this is too easy!" I also like the moment where they enter the blonde woman's apartment and find her body on the bed the editing is very good here, because we get a brief, almost subliminal glimpse of her before the police do, so the first full view of the body is quite surprising. Dickinson strikes me as a very confident director here, willing to play with the material, to have fun with it.

Is it successful as a film dealing with sport?

As someone who can't stand sports soccer, anything with a ball I find the soccer scenes exhilarating. The action is very clear and Dickinson does a deft job of keeping you connected to all the characters while the action is in play.

How well do you think Dickinson's version of 'Gaslight' stands up against George Cukor's?

In a way, Dickinson's is the better of the two films. The Cukor version is more sumptuous, and the look is quite distinctive as always with Cukor's period pieces at MGM, it's visually very rich. But the beauty of the decor overwhelms the drama at times.

More importantly, the dynamics of the two versions are very different. Charles Boyer in the Cukor is much more suave, whereas Anton Walbrook is a sinister autocrat. When Ingrid Bergman in Cukor initially refuses to consider betraying her husband, you have a sense she's still in love with him. But when Diana Wynyard voices the same sentiment in Dickinson's film, it feels more like a fear of defying convention, of being left without a husband in mid-19th-century England. It's less romantic and more believable, more attentive to the way society operates, which is why the psychological reversal at the end has more force when Wynyard turns on Walbrook, you can feel her finally grabbing her chance to vent her hatred, out in the open, and get her revenge. And since Wynyard is less conventionally beautiful than Bergman it gives the film a deeper impact. Dickinson modulates the emotional exchanges very carefully, but he pushes those emotions Walbrook's cruelty and Wynyard's meekness as far as he can. It's no surprise the picture was shot in sequence because the pace feels completely organic, set by the emotional dynamics of the two lead characters. One of the scariest moments is the scene where Walbrook gathers Wynyard and the servants together and reads from the bible: the autocratic head of the household using religion as yet another tool to exercise control.

Do you think his knowledge of the editing process is what makes Dickinson's 'Gaslight' so distinctive?

Dickinson's version sets a faster pace: he never lingers over the visual details the way Cukor does. But regarding his background as an editor, it's interesting to look at The Prime Minister, which he later disowned, but which actually moves quite well. As always, there's genuine subtlety and delicacy in some of the emotional exchanges in the first half of the film you can feel the intensity of the Gielgud and Wynyard characters' love for one another. Dickinson had a great editor's instinct for giving you exactly enough, cutting right at the moment when the emotion registers. And there's a wonderful moment where John Gielgud's Disraeli is making his first, disastrous speech in the House of Commons: at one point, as he's bullied and laughed at by his fellow politicians, he starts to laugh too, out of sheer bitter embarrassment, and then his voice keeps rising. It's quick, and then it's over, the kind of small emotional detail Dickinson is always alive to. He may have been modelling his style on Carn in his early pictures, but he must have had Renoir in mind.

How do you account for the success of 'The Queen of Spades'? Is there anything about it that reflects his last-minute recruitment to the project?

Maybe he worked best under pressure he seemed to excel when he was forced to apply himself to something that was already set up as opposed to the projects he nurtured himself. There are quite a few great film-makers who worked like this ? Jacques Tourneur, for instance, or Raoul Walsh.

How do you think he achieved such a vivid conjuring of 1815 St Petersburg for the film?

He makes very creative use of clutter. In almost every scene with Edith Evans, for instance, the frame is cut in half by a mirror, a chair, something to suggest overstuffed, opulent rooms. It's a B-movie device (Ulmer was very good at it), but it's rarely been used so deftly. And then, of course, there's the very sexual feel of the movie, the way every scene is charged with desire and longing. Dickinson sets it up right away in the bar with the gypsy singing, and connects it to Walbrook's longing to move in more aristocratic circles, to have more money. Finally there's the delicacy and richness of the soundtrack that sound of the aunt's footsteps and cane and her dress moving across the floor is one of the most haunting and effective usages of sound in any movie about the supernatural (and you really need to see a good 35mm print to feel the richness of it it gets a little lost on tape or DVD). It's a great film about longing and lust for sex, money, power.

Is 'Hill 24' the most neorealist film made by a British director? Dickinson's preceding project was to have been "a neorealist film about Malta".

Humphrey Jennings' films are much closer to neorealism and Ken Loach's work is completely in the spirit of the neorealists. Hill 24 doesn't feel like that it feels more like an exceptionally delicate melodrama with a rich sense of place. Like Hitchcock, Dickinson makes the most of place the chases through those hilly streets in Jerusalem, for instance. And there's a sharp sense of cultural differences: in the scene where Mulhare and the girl are sitting in the caf after he's been tailing her, at first the waitress is nice to her, but the minute he sits down she's scornful.

Do you think there are patterns of values and attitudes that pull Dickinson's work together?

There's a strong sense of sexuality and desire, of warring passions and impulses within people, of love turning bad. It's a very physical cinema, a cinema of action. His are movies that move at the speed of life, at the speed of emotions.

And music is very important to his cinema.

His taste in music is wonderful I don't know if it was his idea or Anatole de Grunwald's to have Georges Auric do the music for The Queen of Spades (obviously Auric was already known for the scores for the Cocteau movies), but it fits the picture perfectly. And the scores for his other films are striking, particularly Arthur Bliss' for Men of Two Worlds. But more remarkable is Dickinson's own ear - his sense of sound. Like those ringing bells as Walbrook runs out of the house in The Queen of Spades.

What did British cinema lose when Dickinson gave it up - or when it gave him up?

Quite simply, it lost a uniquely intelligent and passionate artist. They're not in endless supply.