Sex And Self-danger

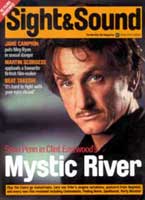

Why does Jane Campion's blood-soaked New York noir In the Cut, starring Meg Ryan, insist on female sexual masochism, asks Graham Fuller.

Manhattan bluestocking, 34, seeks blue-collar Bluebeard for mutually beneficial brief relationship. Must like dirty sex, sleazy bars, trips to the country. Murder weapon not provided...

A maelstrom of psychological conflicts, Jane Campion's In the Cut tracks the vertiginous progress of dowdy writing teacher Frannie Avery, who embarks on an affair with a working-class homicide detective, Malloy, in lowering, humid downtown New York City. She is unconsciously attracted to him, it seems, because he may be the serial killer on the loose in her neighbourhood. Although their frenzied couplings liberate Frannie, when it dawns on her that Malloy might be guilty of the atrocities, she runs from him, her conscious beliefs propelling her into the arms of the actual psycho.

This is a protagonist who clearly shouldn't second-guess herself. But what's a girl to do if her perverse-seeming sexual instincts make more sense than everything her mother ever taught her? And where does directing an erotic story involving the matter-of-fact mutilation of women leave the maker of such anti-patriarchal films as The Piano (1993) and The Portrait of a Lady (1996)? Campion's mesmerisingly ambiguous sex thriller intentionally leaves these questions unanswered.

During the press conference for In the Cut at the recent Toronto International Film Festival, Meg Ryan told reporters she had wanted to play Frannie because the character was "so heartbroken, so shrunken into herself by feminine grief" but "makes a seemingly tiny movement to make a soul connection" omitting the detail that the soul Frannie connects with is very good at cunnilingus. The word "feminine" seemed to baffle the press. One puzzled journalist said he associated femininity with the 1950s, then asked Campion to comment on her interest in the movie which she and Susanna Moore adapted from the latter's 1995 novel as a vehicle for feminist or post-feminist inquiry. Campion refused the bait, allowing only that she saw the thriller genre as "a container for a meditation on the romantic myth in western society".

It's easy to understand why some journalists and audiences might balk at In the Cut as "feminine" or why its director might refuse a debate on its sexual politics. The film spends plentiful time in the macho company of Malloy (Mark Ruffalo) and his wife-beating partner Rodriguez (Nick Damici), who comprise a two-man locker room whenever Frannie joins them. It offers an extreme close-up of a woman's head bobbing over a man's loins shortly before it's severed from her body off screen. It shows the dismemberment, in police photos and at murder scenes awash with gore, of this actress (or prostitute) and two other women.

And there's more. Strippers gyrate with grotesque lewdness in a bar beneath a future murder site. Oblivious to their vulnerability, micro-skirted girls stroll around a neighbourhood strewn with a woman's body parts and a leggy young woman rollerblades down these same deserted mean streets at night. As Frannie heads towards a hell of her own making, Campion fleetingly drops in a shot of a black woman framed in the window of a subway train, for no other reason than that she is alone and therefore at risk.

The unexamined misogyny of most slasher films (and most films in general, not to mention society at large) is the 'norm' against which In the Cut is working. Unsurprisingly, Campion eschewed the clichd approach predicted in Michiko Kakutani's review of Moore's book in the New York Times. Describing it as "a fast-paced murder mystery that moves hurriedly towards its grisly conclusion" and suspecting the influence of Joe Eszterhas and Paul Verhoeven (inappropriately so, given Moore's wit), Kakutani suggested that if the novel were made into a movie, "it would be a stylish, if often farfetched, film noir thriller starring someone like Sharon Stone or Linda Fiorentino. It would most definitely receive an NC-17 rating." This was one of many reviews that remarked on Moore's supposed commercial opportunism and absence of psychological insight while skimping on the book's compelling dialectic between ravenous female lust "I felt such desire for him, such murderous and vengeful desire" - and the male fear of it that is expressed in repugnance and violence.

The film's conclusion necessarily diverges from that of the book, in which the killer slices off one of Frannie's nipples and then cuts, as she tells it, "My face. My throat. My breasts... my hands. My arms." The fate of the screen Frannie is determined by the screenplay's customised narrative logic: her ability to take control of her sexual relationship with Malloy as they tacitly fall in love earns her the right to survive. As for the rating, the movie is being released with an 'R' in America, Campion having agreed in advance to deliver a suitable cut to the distributor. Shots of an erect penis being fellated by the killer's first victim that were included in a version shown to the press have been removed.

Sweat and semen

As a murder mystery, In the Cut is less fast-paced than sluggish. Like the novel, it is a concatenation of coincidences, decoy suspects and mislaid clues, but it is rendered without the tabloid rhetoric of Basic Instinct (starring Stone) or the glib cynicism of The Last Seduction (starring Fiorentino). In its confined spaces and invocations of hatred, distrust and squalor, it is a threnody for a heroine who yearns for death, literally and spiritually, as much as she yearns for love and empowerment, through her ill-advised kinky affair.

As a film noir, In the Cut is a stylistic hybrid, sometimes mimicking the affectless glossiness of rote Hollywood thrillers and love stories especially in the climactic scene, when, as Dusty Springfield sings 'The Look of Love' on the soundtrack, the killer woos Frannie with waltz, engagement ring and razor but mostly clogged and viscous, a paean to New York City at its most relentlessly miasmic. Although In the Cut's thematic analogues are Looking for Mr. Goodbar and especially Klute, with its themes of wilful female self-endangerment and self-entrapment, in its carnality it is reminiscent of Human Desire like that Fritz Lang film, it is sticky with sweat and semen. There's a noir monsoon, too, and a puddle of radiator water on the floor of Frannie's apartment, in which Malloy lies after she has emptied him sexually, but it is blood in which Frannie finally baptises herself a complete woman after eliminating this fable's bogey man.

In place of the symbolically criss-crossing rail tracks of Human Desire's opening title sequence, the visual correlative of the heightened emotions in Campion's film is made up of cutaways to American flags flapping in the breeze and to gothically angled tenement rooftops, fire escapes and water towers. These punctuating shots shown from some unseen prowling observer's point of view clearly connote the post-9/11 landscape in which the very air between the buildings is unsafe, and make Frannie's creeping paranoia pervasive.

Prison bars

"Femininity", however Ryan meant it, had a neurotic connotation for Sigmund Freud, who wrote in a 1932 lecture: "The suppression of women's aggressiveness which is prescribed for them constitutionally and imposed on them socially favours the development of powerful masochistic impulses, which succeed, as we know, in binding erotically the destructive trends which have been diverted inwards. Thus masochism, as people say is truly feminine. But if, as happens so often, you meet with masochism in men, what is left to you but to say that these men exhibit very plain feminine traits?" (See Malloy, below.)

In the Cut, of course, continues Campion's career-long examination of female masochism. Like the symbolically castrated Ada in The Piano and the emotionally brutalised Isabel Archer in The Portrait of a Lady, not to mention the marginalised women in Campion's Two Friends (1986), Sweetie (1989), An Angel at My Table (1990) and Holy Smoke (1999), Frannie is a woman imperilled by her own desires, despite her avowal in the novel that she is not a masochist. If Ada is the prisoner of an arranged marriage and Isabel of a marriage she chose, Frannie is a single woman who, like a character in a famous New Yorker cartoon, holds her prison bars in front of her while floating freely in space.

Campion undercuts familiar notions of femininity. Scored to 'Que Sera Sera', an opening montage establishes the New York setting, but an image of detritus indicates this is not a 1950s Doris Day film, or even Down with Love. In the same spirit of dissonance, Campion introduces Frannie's half-sister Pauline (Jennifer Jason Leigh) before she introduces the protagonist herself. Sipping an early-morning coffee, Pauline dreamily saunters in a garden near Washington Square Park, marvelling as windblown petals fall like snow upon her (as raindrops fall on Frannie as she faces her final ordeal) and a man practises Tai-chi nearby. This Hallmark-card idyll of love and peace is interrupted when Pauline's face looms on the screen in pore-revealing detail.

The film's most shocking images are not those in which Ryan, best known for playing perky girls-next-door in romantic comedies, appears in the nude, but of her mouth, which gapes open increasingly as the lank-haired, long-repressed Frannie discovers her inner voluptuary, or of Pauline's puffy, mascara-blotched eyes and perspiring breasts in a slumber-party scene startling for its unflattering Brobdingnagian close-ups. The bloom is off these roses. Far from alluring, like the airbrushed huntresses in Sex and the City, these women ooze romantic desperation. "I want to get married once," the lachrymose Pauline tells Frannie (the moment accruing sardonic resonance later when we learn her killer ritually proposes to his victims). Sexual Darwinism is Campion's target here.

Lipstick and heels

As Pauline savours the dawn, chimes tinkling in an adjacent bedroom alert us to Frannie waking in bed. Since she seems to fall back to sleep, the rest of the film could be perceived as her dream. Instead of plunging into the oneiric like The Company of Wolves or Mulholland Dr., however, In the Cut occupies an alternative plane its lyrical realism not so heightened that it topples into self-consciously lurid hyperrealism like Taxi Driver or Mona Lisa where fantasy and reality commingle. To this end, cinematographer Dion Beebe throws elements of the compositions out of focus throughout, sustaining a mood of uncertainty.

The film is pitched like a fairytale full of Frannie's wishful fantasies, most of them inspired by Malloy as a masturbatory love object and surrogate father figure who awakens her from her sexual slumbers. In a gothic echo of Isabel Archer's fantasies, Frannie imagines her parents' courtship on an ice rink when her father threw over another girl to win her pretty, blonde mother, later re-experiencing the fantasy as a nightmare in which her father skates over her mother's body, decapitating her.

These jerky, silent monochrome sequences, which could be outtakes from a Guy Maddin version of The Magnificent Ambersons, are crucial to understanding Frannie's neurosis, which originated in her four-times-married father's emotional unavailability and her mother's death. Frannie has the nightmare a few hours after finding Pauline's head wrapped in a plastic bag nestling in a washbasin. Interviewed by Malloy, who leads her from the murder scene having told her he was going on holiday with his kids and ex-wife, Frannie relates her memory of being left in a Geneva hotel for a week by her father when she was ten.

The regressive Frannie's sadistic matricidal dream connected to her terror of abandonment and triggered by her fear of being castrated for having masturbatory fantasies, and by Pauline's killing is overdetermined, as are most dreams: Frannie's mother in the dream is a projection of Frannie herself, suffering at the hands of her father, the seducer in her Oedipal fantasy, who symbolises Malloy in the present. Frannie's mother actually died of a broken heart after her husband left her; Frannie only notices a huge wreath, printed with the word 'MOM', on a subway platform because her own mother's death remains 'live' in her consciousness. And Frannie naturally identifies her mother with the doomed, broken-hearted Pauline, who has been issued with a court order to prevent her from pursuing a married doctor.

One scene in In the Cut literalises fairytale dynamics and atmosphere. Malloy drives Frannie to a rural spot outside the city, like the huntsman commissioned by the Queen to murder Snow White in the Disney animated classic. Beside a lake deep in the woods he fails to slay Frannie or make love to her, so preoccupied is he with the murder investigation. Instead, he trains her to use his gun. The scene is pivotal: Frannie subverting her learned feminine masochism becomes the dominant partner in the relationship. It is echoed later when Malloy, having conceded to Frannie that she is smarter than he is, admits he has fallen in love with her.

Now Frannie triumphantly girds herself in a sexually aggressive uniform of red dress, lipstick and high heels, manacles Malloy to a radiator and rides him to orgasm. She doesn't feminise Malloy to the extent that the Kate Winslet character feminises Harvey Keitel's in Holy Smoke, but when Malloy comments, "I'm starting to feel like a chick," the gender switch is complete. Frannie even usurps Malloy's professional role, simultaneously assuaging her penis envy, maybe. Although it seems she might pay for assuming power when the killer subsequently drives her to his lighthouse lair, she usefully brings Malloy's gun with her.

Inner sanctum

As Frannie's fantasies merge inextricably with her external reality, they hem her into threateningly claustrophobic spaces: the dank basement where she witnesses the oral-sex scene that prefigures the murder mystery and awakens her sexually; subway trains and the detectives' cars; and Frannie's and Pauline's apartments, feminine bowers waiting to be penetrated by Malloy, Frannie's hulking young writing student Cornelius, her ex-boyfriend John, and the killer, who significantly fails to gain entry to her inner sanctum.

These narrow, often dimly lit interiors are redolent of Frannie's psychic state, but also of the film's anguished gynocentricism. When the title appears, the letter 'n' throbs as if desperate to restore itself to the word 'Cut'. The film immediately lurches into a theme of sexual brutalisation when Frannie, who is compiling a list of street slang, explains a meaning of 'virginia' to Pauline with the sentence: "He penetrated her virginia with a hammer." After the killer cuts her between the legs, the dying Frannie in the book meditates on the double meaning of 'cut': "From vagina. A place to hide... someplace safe, someplace free from harm," an ironic riposte to King Lear's invocation of "the sulphury pit, burning, scalding/Stench, consummation."

In the film, Frannie, in shock but surviving, walks from the lighthouse under the George Washington Bridge on to the West Side Highway and seemingly all the way to her Washington Square Park apartment where Malloy awaits on the floor like a tamed (but not housetrained) dog. Perhaps early-morning drivers do not offer Frannie a ride because they think the dried blood caking her dress is menstrual in origin. That would be worse than murder.